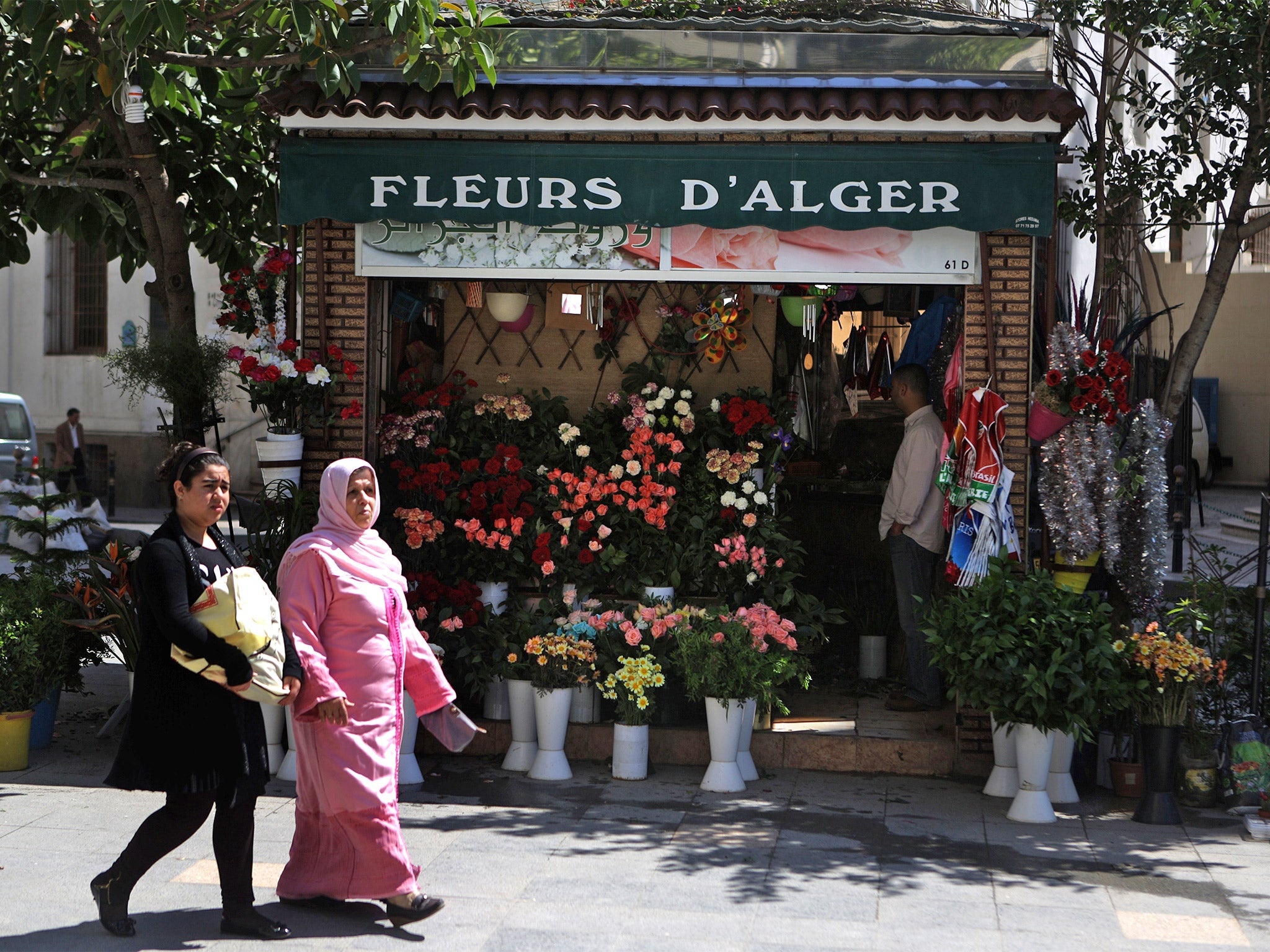

The Real Stories of Migrant Britain: An Algerian scientist adjusts to life working in a kebab shop

In the second exclusive extract from her new book 'Finding Home', Emily Dugan tells the story of Hassiba who left Algeria to marry

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The small classroom in Edinburgh's Southside Community Centre is hushed as lecturer Haidar Mahmoud explains the vagaries of the English language. The pupils sitting inside this converted church are all adults preparing for life in Britain. This is where Hassiba attends classes along with around a dozen others.

Aged 25, she is a newlywed who arrived from Algeria nine months ago and, despite her short stay in the country, already has some of the best English in the class.

She was not that enamoured with the idea of coming to Britain. She came to join her new husband but yearns for home. In Algeria, she left behind a burgeoning career as a geneticist, a luxurious life with her family in a pretty villa. In Edinburgh, she works in a kebab shop and lives in a tiny flat beneath heavy slate skies.

Learning English is her chance to win back at least part of that old life. She has a masters degree in genetics and had been working in laboratories in Algeria; to have a hope of doing the same here, she will need a diploma in English. Speaking after class, Hassiba says: "My husband came here to make his life better, but I only came because of him."

She knew her husband Rachid for two years before she married him. He had lived in Britain since 1999, when he came to London from Algeria on secondment from one of the big oil companies as a petroleum engineer. The placement was meant to be for six months, but at the time Algeria was in the midst of a civil war, with government forces clashing with Islamic extremists and terrorist attacks around the country. He is Algerian and proud of his country, but he was desperate for the safety of Britain. When the six months were up and the company asked him to return home, he decided to run away. He found work as a chef in London, then a job cooking for an Italian family at their takeaway shop in Edinburgh. After more than 10 years living underground in Britain, Rachid sorted out his immigration status. Hassiba currently has a two-and-a-half -year spousal visa with no recourse to public funds and she hopes for a permanent right of residence in the future. But the idea of British citizenship appals her. "No, I would never like to be British," she says. "My country was colonised by the French and independence came at an expensive price. So being British is out of the question."

Hassiba first saw Rachid across the room at a birthday party organised by her sister in 2011. Hassiba thought instantly that he was a good man. "I felt something when I saw him," she recalls with a girlish grin. "I liked his smile. Sometimes, when people are immigrants living outside the country in France and places like that, you can feel it in the way they act when they come back. But you couldn't with him; he acts like he still lives in a village. He's a lovely man."

For three months, Hassiba daydreamed about the smiley man she met at the party. Then one day Rachid contacted her sister and asked for Hassiba's number. Soon, they were chatting with increasing regularity.

When he was in Algeria on visits, they would meet in secret. Under the country's Islamic tradition, men and women were not meant to meet alone before marriage but they wanted to get to know each other first.

Soon, they were meeting often. "We told each other about our lives and our families. Then he went back to Scotland and I thought it was going to be just like that; no marriage."

But once he was back in Edinburgh, the relationship intensified and they would talk for hours on the computer. "He told me about the weather and his life here. He didn't lie to me. He told me the reality that he hadn't got married because he didn't have his immigration papers. He told me he didn't want to get married to an Algerian woman and then not be able to bring them over."

When they finally had their wedding party in November 2013, Hassiba did not relax. Under Islamic custom you are not truly considered married until it is consummated and prayers have been said, but she did not want to risk losing her virginity before the immigration paperwork came through. Once, a marriage would have been a fait accompli for a visa, but the rules have got tighter. She had heard of too many people getting married and sleeping with their husbands only to discover they would not be able to join them in Britain. To get the visa, she had to prove their relationship, showing photos of the wedding, give evidence that Rachid had a secure job earning more than £18,000 a year and pass an English exam called A2. To take the exam costs £100 and it is not simple. Its cost and difficulty have marooned many spouses in their home countries.

"I met some women who failed the exam four times," Hassiba explains.

When it came to choosing where to live, Rachid had stood firm. He has been working at the Edinburgh takeaway shop for so long that the family who own it have expanded the company to several branches. He is a trusted employee and is about to take over the management of the branch he works in. As a chef in Algeria, he would earn a pittance, and he loves his life in Britain.

After cramming for days before, Hassiba passed the English exam first time and got a British visa shortly afterwards. She arrived in the UK in the bitter cold of February. She had never felt more alone. "Where my flat is, you can go three hours and not see any people. It's so cold, really freezing. I imagined it would be cold, but not like this."

Nine months later, Hassiba is sitting in the living room of the flat she shares with her husband. Her home is in a block in prime Old Town real estate, yet somehow architects and town planners have contrived to make an unpleasant ghettoised cul de sac of clustered concrete buildings. Intimidating groups walk between them, their musclebound dogs a few paces in front, off the lead.

Hassiba has seen drug deals and fights on the estate and rarely ventures out alone. It is only mid-afternoon but she is already in her pyjamas. She makes a hot chocolate and gestures at the gathering gloom outside.

"This is my first November. In February it was OK; it was cold, but it wasn't like this. For me, it's depressing when it gets dark this early. If it's dark by 4pm, I don't like to go out."

She loves her husband but she often has doubts about her relocation. "Sometimes I tell myself: 'Why all this?' I just have to prepare my suitcase and come back."

When she was studying genetics in Algeria, her parents were very proud. They did everything to encourage her to keep at her books, making sure she never had to do menial work. Hassiba got a part-time job analysing blood in a laboratory, but never did anything unconnected to her studies. Her final project was an investigation into the genetics of obesity, which pinpointed a common gene present in 76 obese women.

"I haven't got this gene," she laughs, looking down at her tiny frame. She helped present it to scientists around the world, comparing findings with experts in the UK and China.

So it was with a bump that she found herself mopping the floor of a kebab house. For the first few weeks, she could not stop crying. Her husband was worried about her. He helped arrange a meeting with a genetics Professor at Edinburgh University who encouraged her to get an extra English qualification so she could apply for a PhD.

She has been working since the end of March at the same takeaway shop as Rachid. They travel there together – in fact they travel almost everywhere together. "I don't know the area and the people so my husband is scared a lot about me," she says. "I feel sometimes like a child. I need someone with me all the time. The first time I went to the hairdresser's he went with me to explain what I wanted. But now I can understand people."

She has also learnt about racism. "Last Saturday, I had a customer come back in who I had a feeling didn't like me to serve her. There's a girl working with me who's Scottish and she's lovely. She said, 'No, no, it's fine.' But every time I said to this customer, 'Hiya, can I help?' she didn't reply. She asked my colleague for a family meal. "I asked: 'Do you want salt and sauce on the pizza?' And she just blinked at me and made a face. My colleague understood and took the box from my hand. Earlier, I had tried to join in a conversation but she didn't speak to me. I left to do something in the back. When she left the shop, my colleague said "You were right, she is racist because while you were in the back she was speaking about Pakistani shops, saying "I don't like these people, Pakistanis, I don't like foreign people."

Hassiba daydreams about a better job. "When you change your country you find you're in another place in society, far from how you have been. Sometimes, I'm washing up and I remember being in a white coat in a laboratory, looking into a microscope and now look what I'm doing."

She is still hopeful that things will change. More than anything, though, Hassiba hopes to leave. "If we save, we can buy a house in Algeria. This isn't my country. Maybe in 10 or 15 years we can go back home, Inshallah."

'Finding Home: The Real Stories of Migrant Britain' by Emily Dugan (Icon Books, £12.99) is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments