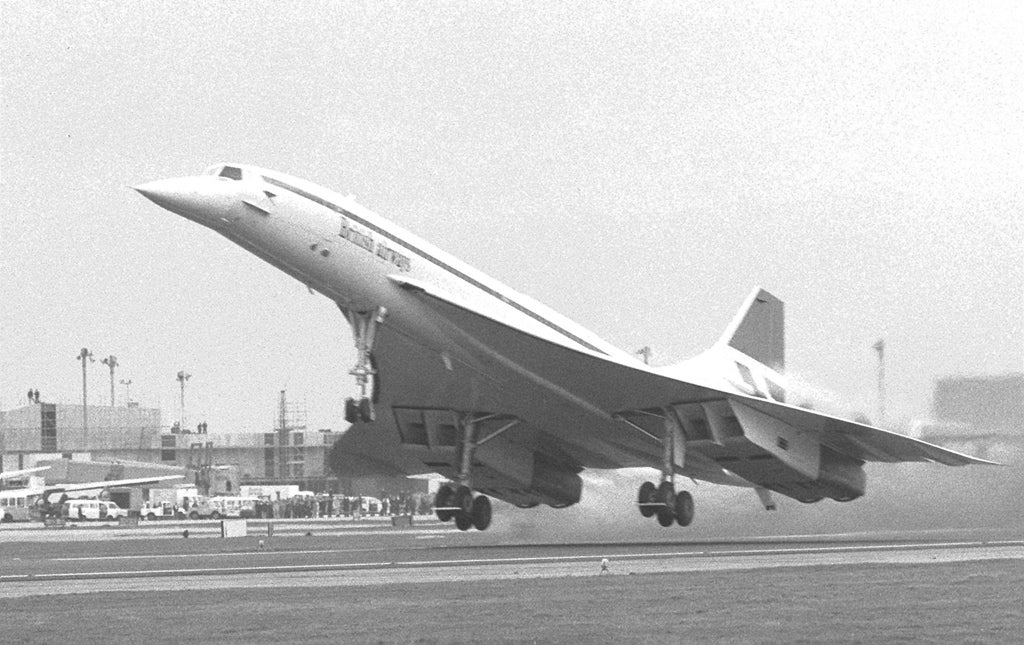

Supersonic flight: Concorde's successors are in the works 15 years on from the Paris crash

One company has started taking orders for a jet that will travel at Mach 1.5

Shortly before 4pm on 25 July 2000, Air France Flight 4590 began to roll down the runway with all the majesty and decibels that had become the signature of a Concorde take-off. Within 120 seconds, the plane had returned to earth in a sheet of flame, killing 113 people as it sliced into the hinterland of Charles de Gaulle airport.

On Saturday, 15 years to the day, flowers were laid at the two memorials commemorating the accident which extinguished the lives of those on board as well as four on the ground, but also sounded the death knell for the 20th-century dream of commercial supersonic air travel.

In the wake of the Paris crash, Air France and British Airways – the two flag carriers which operated Concorde as the apex of Anglo-French technological expertise a generation earlier – spent heavily on improvements, including Kevlar lining to the fuel tanks and new burst-resistant tyres, to rectify the faults behind the disaster and restore confidence in the jet known by pilots as the Rocket.

For a while, Concorde was airborne again, plying the Atlantic in three and a half hours with its payload of monied devotees happy to pay the £8,000 return fare. But if the distressing images of AF4590 lifting off the ground trailing a plume of fire hot enough to melt its wing did not destroy Concorde, then the events of 9/11 did.

In the wake of the terrorist attacks on America, passenger numbers plummeted, and in particular among the business and entertainment jet set that was the plane’s raison d’être. By the end of 2003, both airlines had ended the 27 years of flight that had made it possible to arrive in New York an hour before leaving London.

But as this weekend’s sombre anniversary passes and the question lingers as to whether Concorde’s reign was brought to a premature end, there are signs that the desire for air travel above the speed of sound (761mph or Mach 1) – at least, without being strapped into a fighter jet – did not expire with the plane.

After years of naysayers decrying the proposition of a new generation of supersonic passenger aircraft as economically unviable, one company in recent weeks has started taking orders for a business jet that will travel at Mach 1.5 and start test flights in 2019. Nasa, meanwhile, has begun research into a new generation of jets that will answer the two great problems facing 21st-century supersonic flight – high emissions and the window-rattling phenomenon of the sonic boom.

Few know more about commercial supersonic flight than David Rowland, a former Concorde captain and later general manager of BA’s fleet of the jets. He maintains that the effect of the Paris crash was to sow a seed of doubt that travelling faster than sound was no longer worth the cost it takes to make a reality.

It had taken the political and technological wills of two nations to bring Concorde into existence. The aircraft’s first flight in 1969 and entry into service in 1976 was the fruit not of a commercial contract but of a binding international treaty between two of the world’s wealthiest states and some £1.3bn in development costs. “The French crash didn’t just contribute to the grounding of the Concorde fleet,” says Mr Rowland. It also pushed the idea [of supersonic flight] into the ‘too difficult’ box because it was seen as too dangerous and too expensive.

“The time of the development of Concorde was a different world. We were in business of restoring national prestige. They had to put money into it and we got locked into the project – neither Britain nor France could get out it. That would not happen in the modern world.

“The result is that there is a very exciting challenge out there: to make supersonic passenger flight viable once more. I would say to the next generation: this is your challenge.”

After years of lofty thinking and the unveiling of concept aircraft culled from the pages of Dan Dare, that gauntlet has finally been picked up. For the moment, at least, the future of supersonic flight lies not in re-creating a jet that could match or exceed Concorde’s complement of 99 passengers, but instead one that caters for a niche market of literally high-flying executives for whom money is no object when it comes to shaving a few hours off flying times between Tokyo and Los Angeles or Rio and London.

US-based aircraft manufacturer Aerion began taking orders in May for the AS2, a sleek dart-shaped business jet that can fly up to 12 people at Mach 1.5. The aircraft, which is being produced in collaboration with Airbus, is due to begin test flights in 2019 and comes with a price tag of $120m (£77m) – nearly half the price per aircraft of a Concorde in 2015 prices and roughly double the price of the most expensive private jets currently available.

Doug Nichols, Aerion’s chief executive, insists there is demand for his (and other) sound-barrier breaking jets. One study found a market for 400 aircraft.

“There is no question that there is a robust market for supersonic aircraft, beginning with business jets and later with airliners,” he says. “Supersonic speed will greatly benefit international commerce. We have no doubt that the AS2 will usher in a new era of supersonic travel.”

The key selling point of the proponents of this second generation of Mach 1-busters is the same as that of their predecessors – that most precious of commodities if you are a high-powered deal-maker: time. As the Duchess of York put it when asked about her preference for flying Concorde: “I’m able to take my children to school at 8.30 in the morning, drop them off, then take BA flight 001 to New York, and get to New York at 9.30am, in time for my Weight Watchers meetings and speeches.”

While the AS2 will not quite match the Mach 2 of Concorde, it and its competitors promise to take hours off the flight time of conventional jets – London to New York in four hours 19 minutes; San Francisco to Tokyo in seven hours.

Mr Nichols said: “What our aeroplane can do is convert non-productive time to productive time, whether it’s for business or leisure.”

The new supersonic jets aim to overcome one of Concorde’s weaknesses – its prodigious thirst for kerosene to power its Rolls-Royce Olympus engines – by harnessing aerodynamic technologies and more efficient engines. The AS2 uses laminar flow technology – essentially sharper, carbon fibre wings placed at a particular angle – to reduce air friction. Another American company, Spike Aerospace, is developing a Mach 1.6 business jet that will have its windows replaced with internal video screens, linked to external cameras, to reduce the aircraft’s weight.

But the elephant in the room remains the sonic boom – the shock waves created by an object moving faster than sound which many liken to an explosion. Such is the antisocial status of the boom that all non-military supersonic flight is banned across land in America and Europe.

Aerion says it will get around this issue by flying over land at Mach 1.2 – the point at which the boom dissipates. But Nasa and companies including Gulfstream and Lockheed Martin are experimenting with technologies that change the way the aircraft moves through the sound barrier, creating something akin to distant thunder.

Only time will tell whether the goal of a new supersonic jet age, or indeed its close cousin of rocket-propelled “hyper-sonic” travel at speeds of Mach 4 and above, can overcome the burdens of cost and regulation to come to fruition.

In the meantime, those who enjoyed the first supersonic era still look back with fondness and loss at its passing. “Concorde was a success,” Mr Rowland says. “In terms of its airworthiness, it might well have been possible to still have one or two Concordes flying today. It was an absolute joy to fly. When I first flew it, a large grin spread across my face. It is still there today.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks