How Britain imprisoned some of the first black fighters against slavery

Forgotten history to be revisited with an exhibition revealing how some of the most celebrated black fighters in the early struggle against slavery were once held in a British prison.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A forgotten chapter in black history is to be revisited with an exhibition revealing how some of the first fighters in the struggle against slavery were once held in a British prison.

During the wars against revolutionary and Napoleonic France of the late 18th and early 19th Centuries, when Britain’s black population numbered no more than 10,000, some 2,000 African-Caribbean people were held as prisoners of war in Portchester Castle in Portsmouth Harbour.

In the intervening 200 years, many POWs’ names were forgotten, but now, after years of painstaking research, Abigail Coppins, curator at English Heritage, which manages the castle, has been able to rediscover their identities.

Ms Coppins said: “To discover the identities of 2,000 African-Caribbean prisoners of war imprisoned in Portchester Castle was quite astonishing.

“At a time when the entire black population of Britain was roughly 10 - 15,000, our exhibition completely turns the tables on the views of the period. These names and this exhibition restores a forgotten chapter of black history to England’s story.

“These were not slaves, but free men and women, fighting and in some cases dying for a cause they believed in. “

As the new exhibition at the castle will reveal when it opens on Wednesday, the black prisoners of war included some of the most distinguished fighters in the early battles against slavery in the Caribbean.

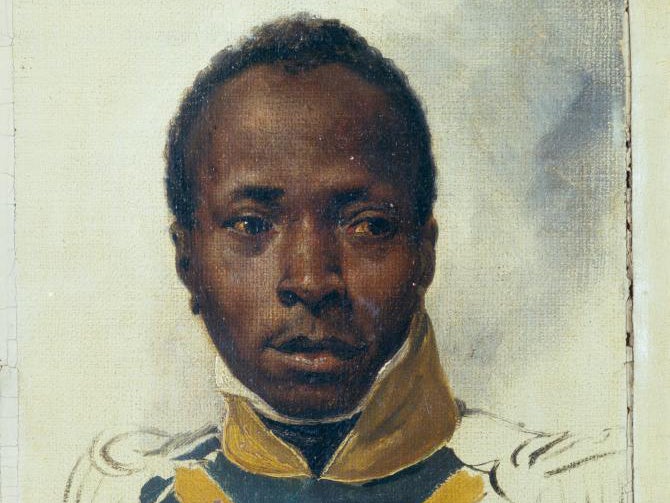

Among those held within the castle walls were Captain Louis Delgrès, who in 1998 was accorded the honour of having his body transferred to the Panthéon, the mausoleum where France inters the remains of its greatest citizens.

Born free on the Caribbean island of Martinique, Delgrès, of mixed race, was captured on St Vincent in 1796, when the British crushed a force comprised of the island’s local population, runaway slaves and French soldiers.

This rebel force had risen up against St Vincent’s British rulers after revolutionary France had voted to end slavery in all its colonies in 1794.

Transported to England with other defeated survivors of what became known as the Second Carib War, Delgrès was allowed to go to France in a prisoner exchange deal that saw British prisoners return to England.

He went back to the Caribbean, but despite being a free man himself, took up arms against Napoleon when the French emperor reinstated slavery.

At the Battle of Matouba on Guadeloupe in 1802, finding themselves surrounded but refusing to be taken alive, Delgrès and about 400 of his followers ignited their gunpowder stores, killing themselves and attempting to take as many French soldiers as possible with them.

Ms Coppins’ research has shown that other Portchester prisoners had fought on St Lucia, which in 1795 had been taken from the British, allowing the island to enjoy what became known as “l’Année de la Liberté” – the year of freedom from slavery.

The year of freedom ended when British troops under Sir Ralph Abercrombie recaptured St Lucia in May 1796, but some pro-French fighters, former slaves among them, slipped into the bush and began a guerrilla campaign that the British took until 1797 to suppress.

The rebels called themselves “L’armée Française dans les bois” (the French army in the woods); the British called them “brigands”.

Among the more charismatic rebels was Jean-Louis Marin Pèdre, whom even his British adversary Brigadier-General John Moore described as a man “with great goodness of heart”.

An illiterate but free-born property owner, Pèdre had been driven into armed opposition to the British by the behaviour of Sir Charles Gordon, who as governor of St Lucia had detained hundreds of people arbitrarily, demanding money for their release.

After his surrender to the British, Pèdre found himself detained in Portchester Castle – alongside his wife Charlotte.

The presence of soldiers’ wives in the prison does not appear especially unusual. Ms Coppins has confirmed that General Marinier, Commander in Chief of the French forces on St Lucia was also kept in the castle with his wife Eulalie Piemont.

At this stage of the hostilities with France, conditions at Portchester, a castle dating from Roman times, were not especially arduous.

Because many of the black prisoners had arrived at the castle in attire suitable only for a Caribbean climate and suffering from chilblains, the prison officers issued them with thick woollen vests and extra socks.

It was, however, reported that it was not immediately possible to find shoes that fitted them “the West Indians having all large feet”.

The prison doctor was, though, able to arrange for them to be given additional provisions, which included extra potatoes, soup before bedtime, and beer flavoured with ginger, which was thought to be warming.

Deaths were rare, and there were some limited opportunities for exercise, because in response to prisoners rioting over cramped conditions in 1743, during the War of Austrian Succession, a fenced “airing ground” had been built in the castle grounds.

Indeed, at about this time, there were complaints that while the French subjected English POWs to “inhumanity unprecedented in the annals of civilised nations”, the British looked after their prisoners so well that, as a letter writer to the Gentleman’s Magazine put it in 1793: “The Sans Culottes we hold in prison never lived so well in their lives before.”

During this period conditions in Portchester and elsewhere remained sufficiently relaxed for there to be regular markets where the British public would be admitted to buy or barter articles from the prisoners.

Prisoners keen to boost their resources of either money or food were said to have fashioned scale models of ships or musical instruments built from the bones of their meat rations.

At Portchester, during the Napoleonic wars, a group of prisoners from mainland France were even able to create a theatre where the quality of their music, dance, scenery and costumes approached that of the professional stage. Monsieur Carré, the troupe’s leader was sent new plays by the Théâtre Feydeau in Paris.

As part of the new exhibition, English Heritage has now installed a replica of the theatre in the ground floor of Portchester’s great keep, featuring a wooden stage complete with the original backdrop of the Pont Neuf in Paris.

And on Wednesday, a local audience will be treated to a special staging of one of the prisoners’ original plays, entitled Roseliska. An original manuscript for the three-act melodrama survived because it was dedicated to Captain Pearson, the man in charge of the prison, and was handed down through generations of the British officer’s family.

Despite such apparently friendly relations between warders and inmates, however, the prison was not immune to racial tension.

The guards could not stop prisoners of war from mainland France stealing the Caribbean contingent’s clothes, and this eventually led to black and mixed-race soldiers being accommodated separately on two new prison ships.

The African-Caribbean men and women were eventually exchanged for captured British soldiers and sent to France.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments