Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Quaazy. Zowpig. Splawder.

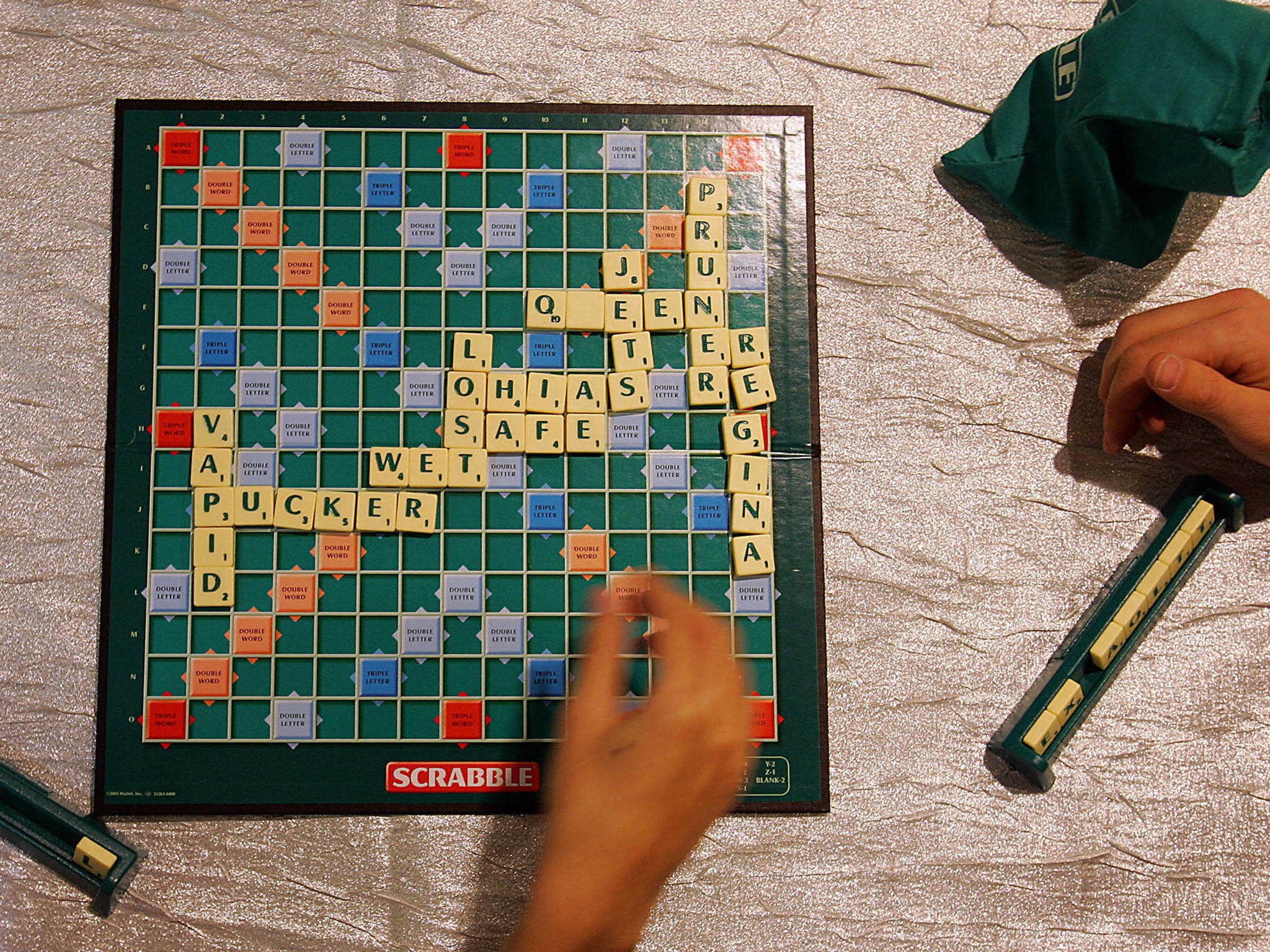

They may not be everyday conversational terms but, according to one American researcher, the recent inclusion in Scrabble’s official dictionary of modern and dialect words like these has rendered the board game’s scoring system dramatically out of date.

Joshua Lewis argues that, while the letters Q and Z may once have earned their 10 points per use 75 years ago when Scrabble was created, the letters are now far more common than they used to be.

Speaking to the BBC, Mr Lewis said “Among the notable additions are all of these short words which make it easier to play Z, Q and X, so even though Q and Z are the highest value letters in Scrabble, they are now much easier to play.”

Mr Lewis is a researcher and creator of a software programme which allocates new, up-to-date values to Scrabble tiles.

His programme, entitled Valett, recalculates the letter valuations by looking at three things; the frequency of the letter in the English language, the frequency by word length and how easy it is to play the letter with other letters.

According to Mr Lewis's system, X should only be worth five points, not the eight points it is worth now, Z should be worth six points, not 10 points, and M should be changed from three points to two.

Valett is not all about downgrading tiles though, as many letters that were common 75 years ago are harder to use in modern language.

U, for example, is currently only worth one point but, according to Valett should be upgraded to two. G meanwhile, which is traditionally valued at two points, requires bumping up to three.

While updating the tile values in Scrabble has been argued for decades, the system doesn’t have the support of official Scrabble players’ groups.

John Chew, co-president of the North American Scrabble Players Association says there would be “catastrophic outrage“ if the scoring system were to change.

He added: ”Some people would just continue playing with the old tile distributions because people who've played the game often enough tend to remember that the Q is worth 10 points, the Z is worth 10 points and so on.“

He also believes experienced Scrabble players understand that tiles have an “equity value” - a value that far outstrips their face value in the middle of a game because they can earn huge points.

Mr Chew can sleep easy however, as the game’s manufacturer Mattel says it has “no plans to change Scrabble tiles”.

Philip Nelkon, Scrabble's UK representative, added: “It is not a game where fairness is paramount, it is a game of luck and changing the tile values wouldn't achieve anything.”

American architect Alfred Butts invented Scrabble in 1938, calculating a value for each tile based on how frequently each letter appeared on the front page of the New York Times.

The method proved controversial from the off, with players initially complaining the game favoured journalese instead of not spoken English, and more recently accusing the scoring system of being out of date.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments