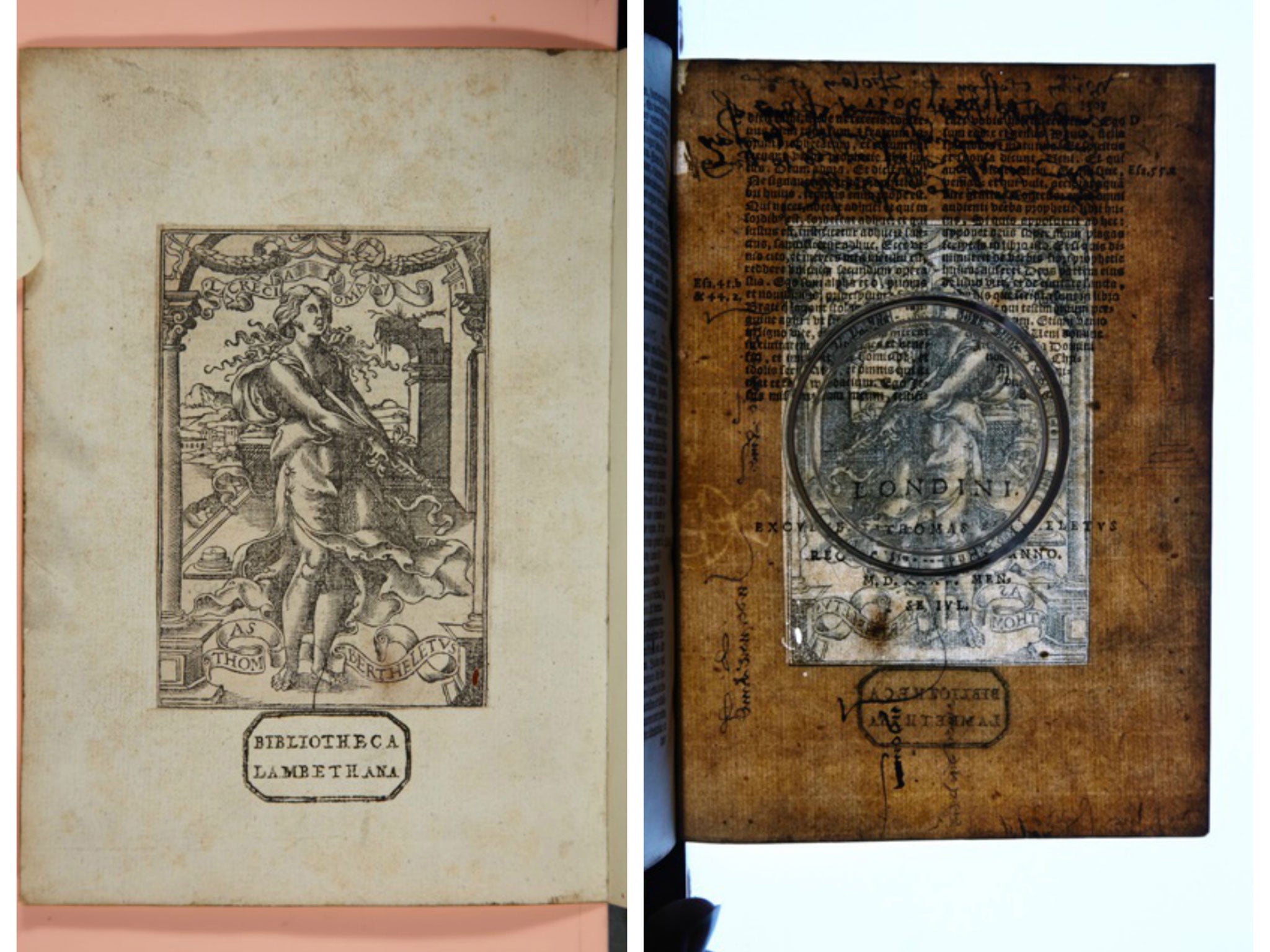

Hidden notes found in England's oldest bible, printed by Henry VIII

The book was published by Henry VIII in 1535

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Secret notes, hidden for 500 years in England’s oldest bible, have been discovered.

The notes were written on parts of the book, published by Henry VIII in 1535, which had been pasted over with heavy paper, obscuring them from view.

The book was being housed in Lambeth Palace Library, London, and Dr Eyal Poleg, of Queen Mary University made the discovery while carrying out research.

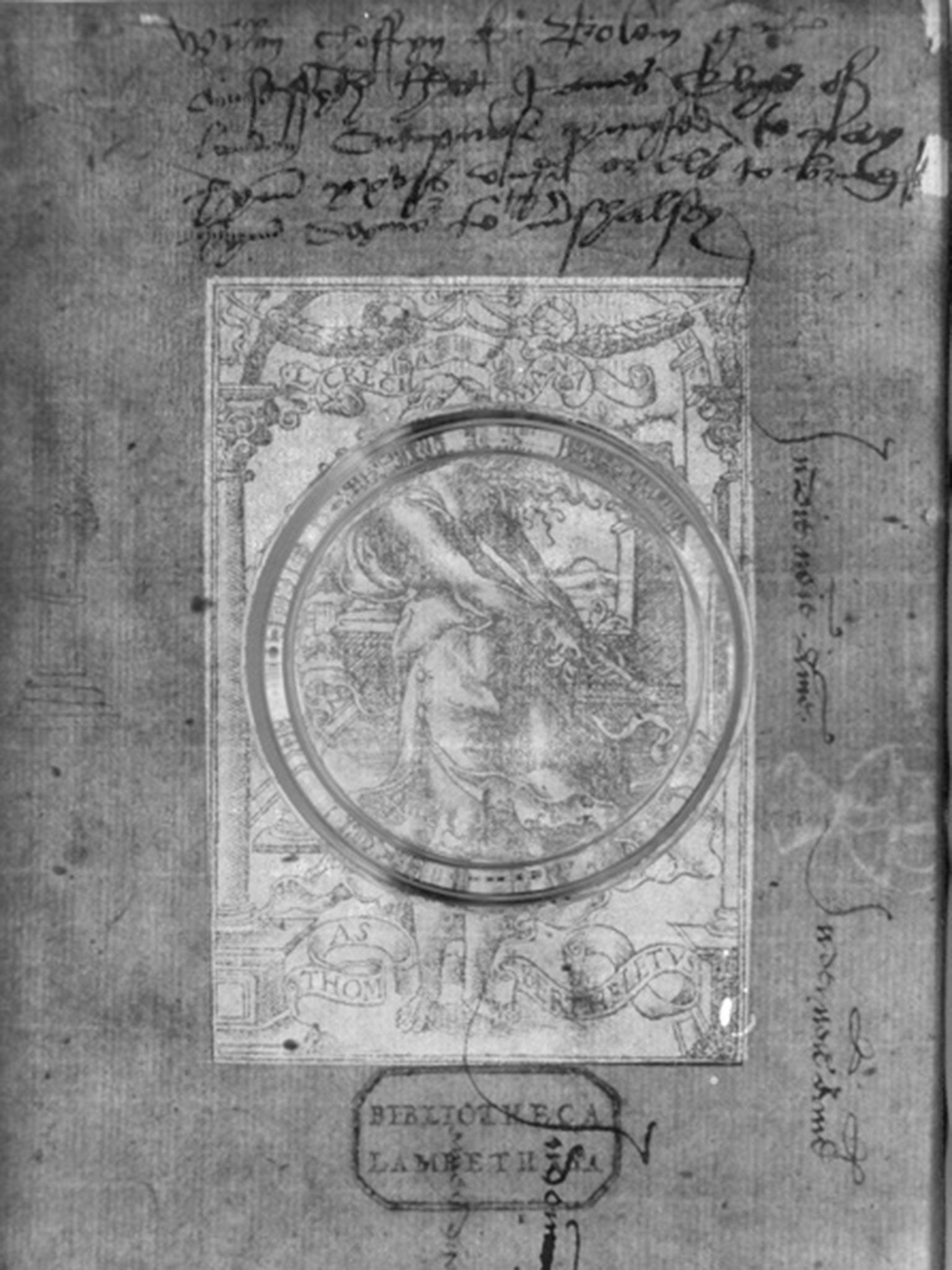

Using specially developed 3D X-ray technology, Dr Poleg was able to reveal the notes.

“We know virtually nothing about this unique Bible – whose preface was written by Henry himself – outside of the surviving copies,” said Dr Poleg.

“At first, the Lambeth copy first appeared completely ‘clean’. But upon closer inspection I noticed that heavy paper had been pasted over blank parts of the book.

“The challenge was how to uncover the annotations without damaging the book”

The handwritten notes are copied from the ‘Great Bible’ of Thomas Cromwell, who was one of the main advocates of the English Reformation, and were written between 1539 and 1549.

They were hidden with the paper in 1600.

One example reads: "'On the iij Sonday [of Lent] | [E]phe. v. a. be ye therfore follo. | Lk. xi. b. and he was casting out."

Dr Poleg told the Mail Online: "This means that the text to be read at Mass on the Fourth Sunday of Lent is the Letter to the Ephesians 5:1 (beginning with 'be ye therfore’) and Luke 11:14 (beginning "and he was casting out")."

According to Dr Poleg, the find is significant because: “Until recently, it was widely assumed that the Reformation caused a complete break, a Rubicon moment when people stopped being Catholics and accepted Protestantism, rejected saints, and replaced Latin with English.”

“This Bible is a unique witness to a time when the conservative Latin and the reformist English were used together, showing that the Reformation was a slow, complex, and gradual process.”

In addition, further notes were discovered on the back pages of the bible; a handwritten receipt between two men: Mr William Cheffyn of Calais, and Mr James Elys Cutpurse of London.

‘Cutpurse’ was a medieval English word for pickpocket.

The note is a record of a transaction between the two men. Cutpurse promises to pay 20 shillings to Cheffyn, or go to Marshalsea prison in Southwark.

Dr Poleg later discovered that Cutpurse had been hung in Tybourn in July 1552.

“Beyond Mr Cutpurse’s illustrious occupation, the fact that we know when he died is significant. It allows us to date and trace the journey of the book with remarkable accuracy – the transaction obviously couldn’t have taken place after his death,” said Dr Poleg.

He added: “The book is a unique witness to the course of Henry’s Reformation. Printed in 1535 by the King’s printer and with Henry’s preface, within a few short years the situation had shifted dramatically. The Latin Bible was altered to accommodate reformist English, and the book became a testimony to the greyscale between English and Latin in that murky period between 1539 and 1549.

“Just three years later things were more certain. Monastic libraries were dissolved, and Latin liturgy was irrelevant. Our Bible found its way to lay hands, completing a remarkably swift descent in prominence from Royal text to recorder of thievery.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments