Sketches show Irish nationalist hero Roger Casement in his final days in the Tower of London before execution

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

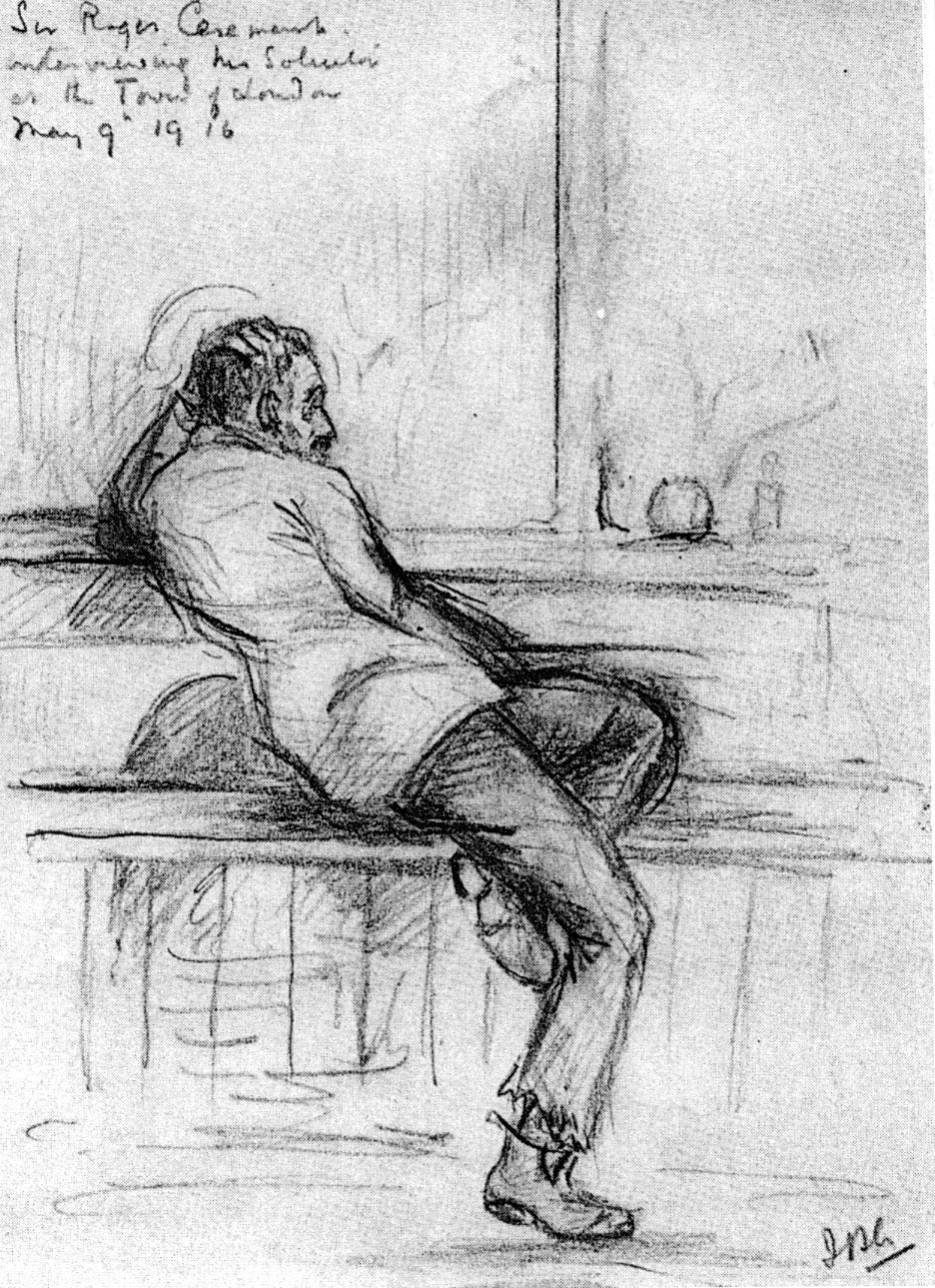

Your support makes all the difference.The sketch of Sir Roger Casement in the Tower of London in 1916, drawn three weeks after he was arrested after landing from a German submarine in Ireland, shows him reclining on a bench. One leg is crossed under him and the other hangs down, revealing a torn and ragged trouser end and a battered boot without any shoelaces.

He had not been allowed to change his clothes in the weeks after he was captured in an effort to demoralise him, and his laces, necktie and braces were removed in case he should try to commit suicide.

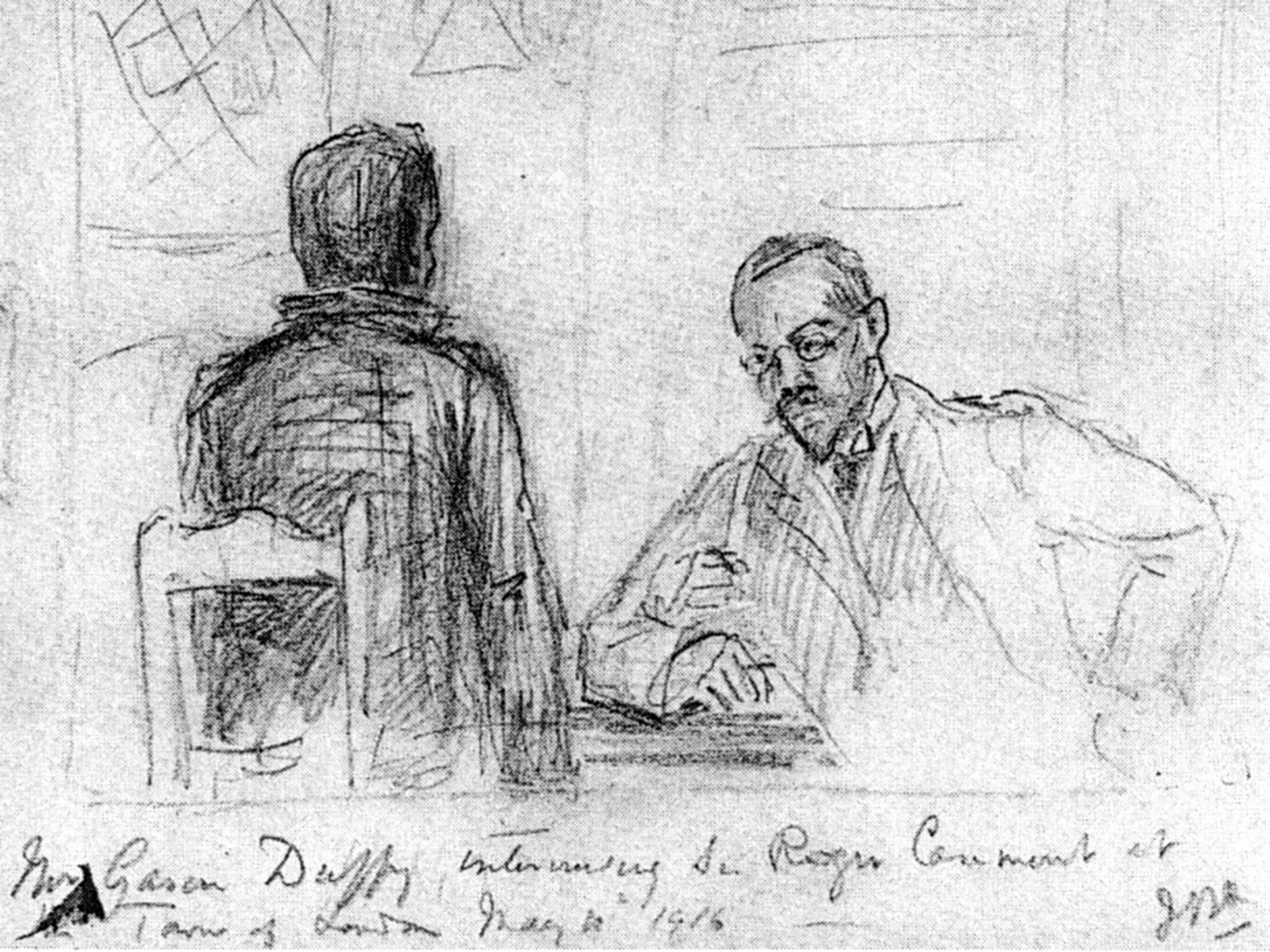

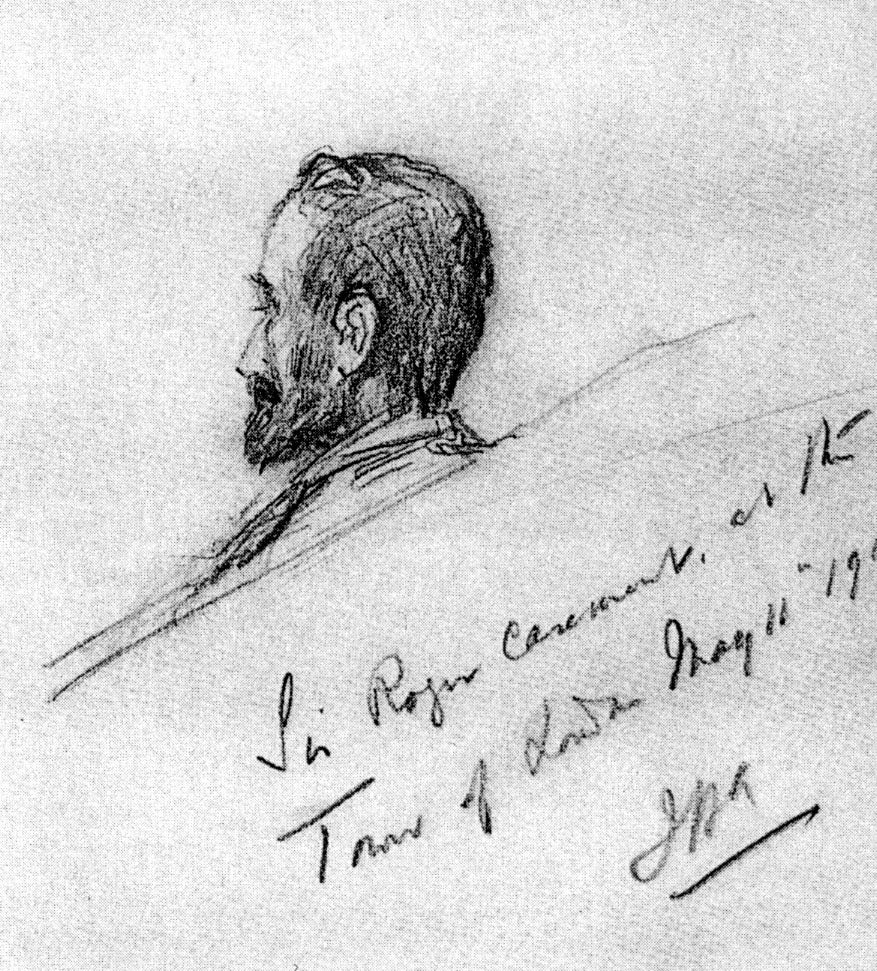

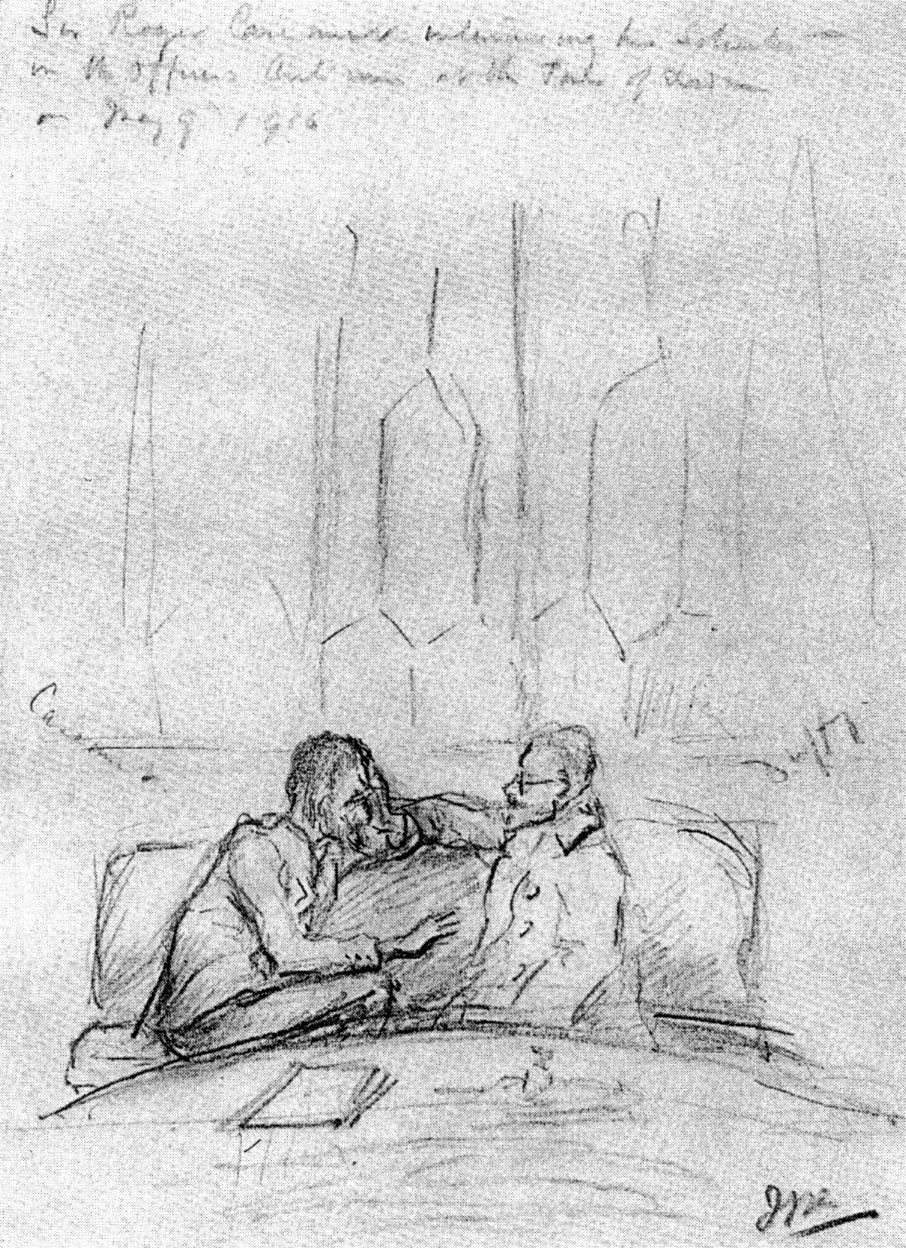

The five drawings, unpublished for a century, give a vivid and unique impression of Casement, one of the extreme Irish nationalist leaders in the days leading up to 1916 Rising, after he was detained in Kerry and before he was indicted for high treason; the charge led to his three-day trial at the Old Bailey on 26-29 June and his execution by hanging in Pentonville Prison on 3 August.

“The images are so important because they are the only ones of Casement in the Tower and the first of him in captivity,” says Angus Mitchell, a lecturer at Limerick University and the author of 16 Lives: Roger Casement, the recently published biography of Casement.

The sketches have a peculiar history which helps explain why they have remained unknown for a hundred years, despite a great number of books and articles about Casement. They were drawn on 9 and 11 May 1916 by Major John Bernard “Jack” Arbuthnot, my grandfather, who was an officer in the Scots Guards, though also an amateur artist, cartoonist and part-time journalist.

After fighting in the battle of Ypres on the Western Front at the beginning of the First World War, he was stationed in Whitehall in London in 1916 when he was put in charge of supervising Casement’s meetings with his solicitor, George Gavan Duffy, in the Tower.

Major Arbuthnot evidently had sympathy for Casement because he expanded his authority by telling the prisoner’s cousins, Gertrude and Elizabeth Bannister, who had been desperately searching for him, where he was imprisoned. Gertrude later recorded that “we saw a certain Major Arbuthnot who showed courtesy and sympathy".

He contacted the Governor of the Tower for them so they could visit Casement and told them to send in clothes for him. During their visit, the Major brought Casement to see them and ordered the two soldiers guarding him out of the room while the Bannister sisters spoke to him.

Their meeting must have been just after Major Arbuthnot sketched Casement on 9 and 11 May, when he met George Gavan Duffy and was still wearing the same clothes, described as being by now filthy and verminous, which he was wearing when arrested at Banna Strand in Kerry on 21 April. Four of the drawings are in pencil and one is in pen and ink and all are signed and dated by Major Arbuthnot with brief captions about where and with whom Casement is pictured.

Given Casement’s fame as an Irish patriotic martyr and the controversy over his sexuality, it is surprising that the only pictures of Casement in the Tower were not published in the century after he was hanged. Soon after the Bannister sisters saw him, he was moved to Brixton prison during his trial and then to Pentonville where he was hanged.

His notoriety was partly fuelled by disputes over the so-called “Black Diaries”, which may or may not have been forged, in which Casement describes his life as a homosexual and which were covertly used by the British Government to damage Casement’s reputation and undermine the campaign to prevent his execution.

The reason the sketches remained unknown is that Major Arbuthnot himself did not care about their historic significance and kept them in Myrtle Grove, his Tudor house in the town of Youghal in Ireland, where he died in 1950. He was well-off and never sold any of his numerous drawings, paintings and cartoons, though they are of high quality. He was a High Tory who lived by his own rules and considered his kindness to Casement in the Tower as very much his own business.

I was shown one of the Casement drawings on a wall in Myrtle Grove when I was a child, but I was not very interested at the time. I did not see any of the pictures again – I did not know that there were five of them – until Mr Mitchell, the biographer of Casement, whose life he has studied for twenty years, made contact to explain that he had copies of four of the Arbuthnot sketches that he himself had copied from an auction house’s catalogue that he had found in a file in the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Casement was at the centre of the 100th anniversary of the Easter Rising, which has just been celebrated in Ireland. Mr Mitchell says that his importance as a human rights campaigner who, as a British consul in the Congo and Brazil, exposed the enslavement and extermination of native people, is increasingly recognised after long being masked by disputes over his sexuality and the circumstances of his execution.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments