Revealed: Surrogate births hit record high as couples flock abroad

But Foreign Office warns of red-tape minefield for those so desperate for a baby that they go overseas

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Record numbers of British children are being conceived through surrogacy, according to official figures seen by The Independent on Sunday.

The number of babies registered in Britain after being born to a surrogate parent has risen by 255 per cent in the past six years, amid mounting concerns that legislation has not kept up with demand.

Last year, 167 babies were registered in Britain as born to a surrogate parent, up from 131 in 2011. This is a dramatic increase from 2007, when only 47 parental orders were filed to register a baby born through surrogacy, figures from the Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service (Cafcass) show.

The upward trend is continuing. In January alone this year, 24 babies were registered to British parents after a surrogacy, suggesting that 2014 is already set to be a record year.

Britain’s first conference examining best practice and the latest legal situation in surrogacy begins this weekend in Windsor. It has been organised by Families Through Surrogacy (FTS), an international not-for-profit group started by Sam Everingham, an Australian who is himself a parent of surrogate children.

In Britain, surrogacy is legal only if it is done for altruistic reasons – for example, as a favour to a friend or relative – and the only acceptable payment is “reasonable expenses”. This means most prospective parents turn to foreign markets to pay for someone who will carry out the pregnancy.

Data collated by FTS from 12 major overseas surrogacy clinics show an 180 per cent increase in intended parents from the UK over the past three years.

However, British embassies and high commissions say they are dealing with rising numbers of people encountering trouble while trying to collect babies conceived through surrogacy overseas, at the same time as the Foreign and Commonwealth Office reports that “more and more” parents are heading to the US, India, Ukraine and Georgia to enter into surrogacy arrangements.

The FCO has just launched a campaign warning parents of how complicated the surrogacy process can be, to ensure more of them research international laws before embarking on it.

Daisy Organ, children’s policy adviser at the FCO, said: “Many of the problems are around fraudulent documents and underestimating how long it takes to go through the process.

“Many parents are understandably focused on the baby being born, but then haven’t focused as much about what happens next and how to get home. It’s not automatic that on day one your child will get a British passport – it can take weeks, if not months.”

Ms Organ said the lack of regulation internationally, as well as being an issue for perspective British parents, was likely to mean surrogate mothers are exploited, particularly in developing countries.

“[The FCO] does not have personal experience of surrogate mothers being taken advantage of,” she said, “but the media reporting and the lack of regulation suggests that it is a real risk.”

Unethical and unregulated medical tourism companies can flourish in this setting, selling on surrogacy “solutions” to Westerners, and negotiating poverty pay rates for mothers in countries such as India and Thailand.

Government data on surrogacy does not give the full picture of the scale of it in Britain, as experts believe that hundreds, possibly thousands, of babies are brought back to the UK without an official parental order.

Officially, all British children born through surrogacy should be subject to a parental order, but in some countries, such as India, parents who give the embryo automatically appear on a baby’s birth certificate without the need for an order.

Mr Everingham, whose daughters were both born via surrogacy in New Delhi in 2011, said: “Hundreds of UK couples go offshore each year in search of a surrogate to carry their child. Government figures are likely to far underestimate the real numbers, given that many UK citizens don’t bother applying for parental orders, believing a UK passport for their child or children is sufficient protection.”

Natalie Gamble is a solicitor who fought Britain’s first legal case over a international surrogacy case in 2008, after the UK authorities regarded a Ukrainian surrogate mother as the legal parent of twins created using embryos provided by a British couple.

Ms Gamble’s firm has since advised on 71 UK surrogacy cases between 2009 and 2013. Around a third of these related to surrogacies in India, another third in America and the remainder from a range of countries, including Ukraine, Georgia, Thailand, Russia and China.

Ms Gamble says Britain’s dated laws are creating a minefield for parents. “They are relics created in the 1980s, and they have never been updated and cannot cope with the strain of international surrogacy,” she said.

“UK law says the surrogate and her husband are legal parents, whereas foreign law says the opposite.

“You get a head-on collision where British parents are not recognised as legal parents back in the UK and then cannot transfer the nationality of the child.”

Case studies: ‘We fertilised 12 eggs: six were Steve’s and six were mine’

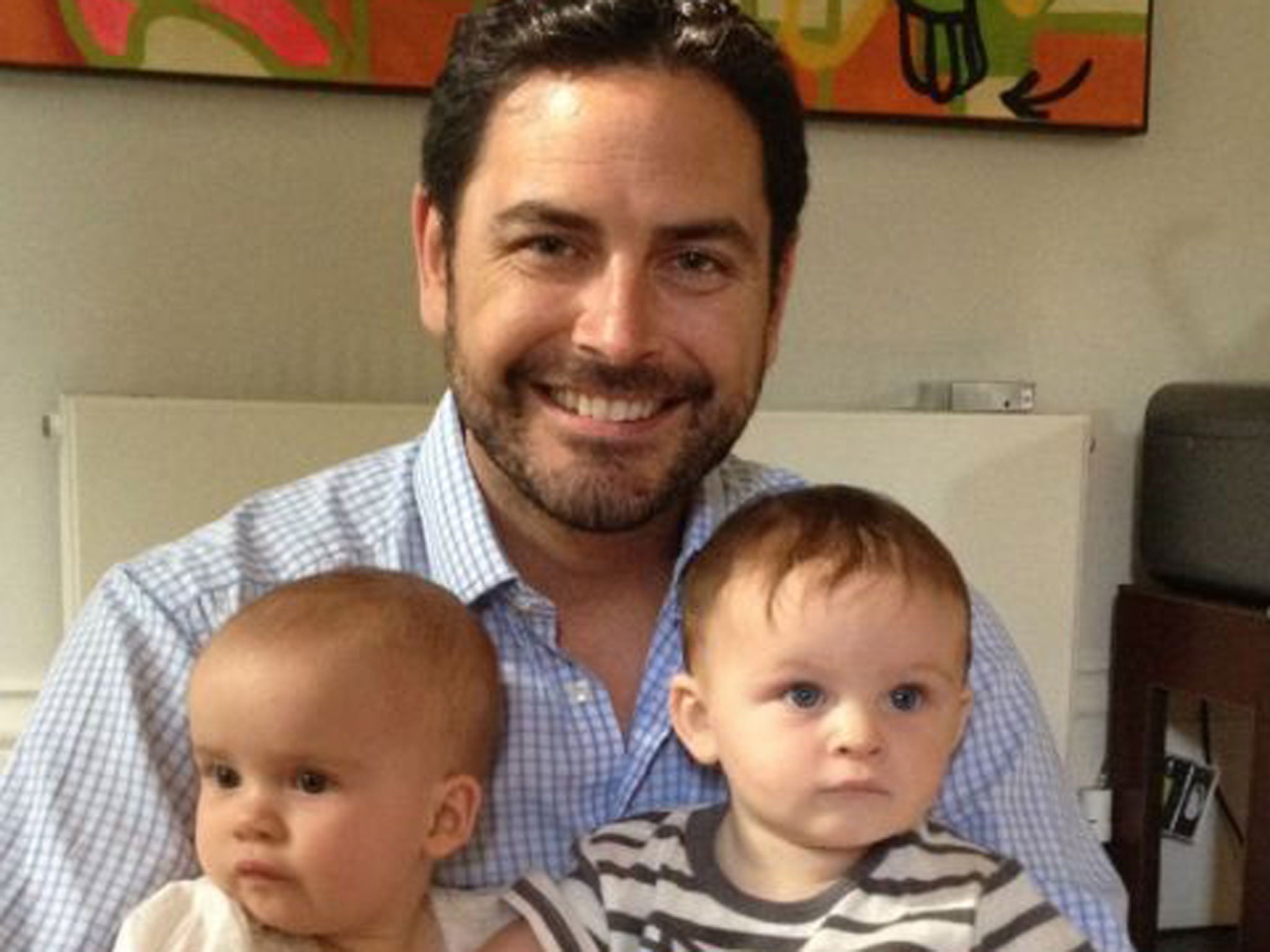

Richard Westoby, 38, from west London, and his civil partner, Steven, had twins Alexander and Liliana, 17 months, via a surrogate in America.

“We looked at adoption and co-parenting, but we just felt we wanted a genetic link to the family. My partner is American and we felt the legal framework there would be good as it’s the global benchmark. We chose a surrogacy agency blindly and found a surrogate in Arizona. We paid our surrogate Angela $25,000 (£14,918) as a fee. On top of that we paid her travel expenses, maternity clothing and medical costs. It was enough to put her child through university, but she did it because she liked being pregnant and wanted to help people who couldn’t have a child. We keep in touch, we email every two or three weeks with pictures of the children.

“It was gestational surrogacy, so we took an egg from another donor. We’re both white, so we wanted a white donor. We’re six foot five and wanted someone between five foot five and five ten. We didn’t want anyone with a BMI over 25 and we wanted someone who had gone to university. You’ve got 30 different filters and you have medical information, psychological history and the medical history of the donor’s sisters, parents and grandparents. We decided not to choose anyone with breast cancer in the family, as that’s genetic. We also wanted a known donor so our children can know and have contact with them if they want.

“We fertilised 12 eggs, six were Steve’s and six were mine and we implanted one child from each of us. We know whose is whose, but we don’t tell anyone. I don’t want to; they’re both my children. It’s the best thing I’ve ever done and it changes everything. I was in finance but I’m a stay-at-home dad now.”

‘We had the frozen embryos. We waited two weeks to find out if she was pregnant’

Carolyn Bresh, 47, from north London, had Sam, four, after Carolyn’s sister Deborah Paton, 41, stepped in as a surrogate.

“We had been trying for children for maybe five years. We’d had seven rounds of IVF in this country and in Spain, and we had run out of options. We would have considered adoption but we’re old in parenting terms, and when we told the council our age, that didn’t seem to be an option. They asked us to consider fostering, but I didn’t think I could deal with that emotionally.

Friends encouraged us to look at the US, where effectively you can pay, but it seemed like a step too far for us. It was less about the financial side – we just weren’t sure about going through a book and selecting somebody.

“Then my sister stepped forward. I had asked my mum to explain to my family that we’d stopped trying. Within 24 hours of her telling my sister, she said, ‘I can do it.’ She has two children, a daughter and a son, and she said, ‘I can solve this.’

“She was insistent that it could not be an embryo from her. That was a ground rule.

“We had frozen embryos and it was a two-week wait to find out if she was pregnant. It was an incredible feeling when she told me she was. It was amazing she offered to do it.

“I tell Sam how he was born because we are determined that it’s not a secret. Without her gift he would not be here.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

2Comments