Refugee crisis: European leaders blamed for record high deaths in the Mediterranean

Exclusive: Report author says politicians have been ‘wantonly ignoring’ reality to maintain ill-informed government positions

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Britain and other European nations are making the refugee crisis worse by forcing people fleeing conflict and persecution to undertake covert and treacherous journeys, a report has found.

The damning report by the Unravelling the Mediterranean Migration Crisis (Medmig) project, seen exclusively by The Independent ahead of its release, concluded that the refusal to open up legal routes for those seeking safety in Europe has increased demand for people smuggling on ever more dangerous routes.

Operations to combat the thriving trade has driven the use of smaller and less seaworthy boats to cross the Mediterranean, contributing to the deaths of almost 4,000 migrants so far in 2016 – now the deadliest year ever for refugees.

Professor Heaven Crawley, an author of the report from Coventry University’s Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations told The Independent politicians have been “wantonly ignoring” the reality of the crisis to maintain ill-informed government positions.

“The problem is there’s a huge political agenda around migration, so more pragmatic of effective alternatives are being overridden by political aspirations of leaders across the EU,” she said.

“They’ve backed themselves into a political corner where it’s very difficult to do anything else.”

Professor Crawley said the UK’s initial refusal to resettle refugees who had already crossed into Europe was “appalling” as an estimated 60,000 migrants remain trapped in Greece alone.

"All that response does is reinforce some of the perceptions that if you’re a ‘proper’ or ‘genuine’ refugee you stay in a camp and wait for however long it takes to be rescued, and those who make it to the EU are punished,” she added. “Families find that inconceivable.”

Far from combating people smuggling, the report found European operations, border closures and the tightening of asylum regulations in several countries was directly driving refugees into their hands, with every single person interviewed using a smuggler for at least one leg of their journey.

Dr Franck Duvell, from the Centre on Migration Policy and Society at the University of Oxford, said: “EU politicians and policy makers have repeatedly declared they are ‘at war’ with the smugglers and that they intend to ‘break the smugglers business model’.

“The evidence from our research suggests that smuggling is driven, rather than broken, by EU policy.

“The closure of borders seems likely to have significantly increased the demand for, and use of, smugglers – who have become the only option for those unable to leave their countries or enter countries in which protection might potentially be available to them.”

One in 10 refugees interviewed in Greece for the report had attempted to find a legal way to enter Europe but failed, resorting to almost a hundred different and potentially deadly routes that often cost far more than a legal journey.

Many used smugglers for boat crossings but needed them to leave conflict-ridden countries like Syria, where hostile governments or militant groups have attempted to seal borders.

European politicians frequently depict smugglers as part of vast criminal networks but the Medmig report found they are often found in asylum seekers’ local communities or social networks, with names and numbers travelling by word of mouth.

State officials, the military, law enforcement, and border guards are also involved in smuggling, researchers said, citing numerous testimonies of smugglers bribing police in Greece, Turkey and other countries of transit.

Boat journeys across the Aegean Sea have dropped sharply since the controversial deal made between the EU and Turkey in March, which is seeing migrants arriving on Greek islands detained under the threat of deportation.

The agreement’s impact has been widely hailed a success but it has been made fragile by growing tensions with Ankara. “Most people agree that it’s only a matter of time before that deal falls apart or people find another way,” Professor Crawley said.

Meanwhile, the number of asylum seekers arriving from North Africa has remained consistent despite high-profile anti-smuggling initiatives, with almost 160,000 migrants and refugees landing in Italy so far this year.

The desperate journeys have made the central Mediterranean the deadliest sea crossing in the world, seeing asylum seekers drown, suffocate or die of fuel inhalation in overcrowded boats.

In previous years smugglers commonly used repurposed commercial vessels fitted with satellite phones and GPS, or large fishing boats, but to evade detection by the EU’s Operation Sophia and authorities in North Africa, they are now loading migrants into dinghies incapable of journeying hundreds of miles to European shores.

Echoing previous warnings by the UN, the Medmig report said smugglers responded to increased controls by “looking for alternative routes or sent boats onto the water at night when they were less likely to be detected and also to be rescued”.

Treacherous sea journeys are far from the only risk – researchers said the failure of the EU to resettle refugees or provide legal routes were forcing people to flee from one conflict zone to another at the risk of violence and abuse by both people smugglers and state authorities.

More than three quarters of people interviewed for the research in Italy and Malta had experienced physical violence, with almost a third watching their fellow migrants be killed or die of illness.

Among the horrors described are border guards shooting migrants trying to leave Iran, Syria and Eritrea, and people being raped, kidnapped, beaten and tortured or simply left to die in the desert while journeying through countries including Algeria and Niger.

Many described a living nightmare in Libya, which remains in a widespread state of lawlessness following the British-backed removal of Muammar Gaddafi and subsequent civil war, with rival armed groups including Isis locked in bloody competition for control.

Many refugees interviewed by Medmig reported being detained and tortured either for ransoms of thousands of dollars, or forced into labour or prostitution to earn their freedom.

Libya was once a popular destination for migrant workers from elsewhere in Africa but the deteriorating situation has driven many of those who previously saw it as a safe haven to flee across the Mediterranean.

A Gambian man interviewed by Medmig told how he was trapped into forced labour by the promise of a prosperous construction project.

“I spent nine months in prison, it was too long … we were two, three, four days without food or water, many people lost their life there,” he said.

“You work for them, when somebody dies you have to move the body for them, they take you and tell you to throw the body in the ditch. It is inhuman.”

Leaving Libya via land is not considered an option, with widespread reports of border guards and militias shooting those trying to get out.

A Nigerian woman said she saw a border guard pour petrol on a migrant and set him on fire, adding: “You cannot get out of Libya alive. You have to give your money to someone and hope they will take you. They tell you, you must take the boat.”

Medmig researchers says the country was one of many examples where “refugees” and “economic migrants” cannot be clearly defined.

“The definition is just out of kilter with reality,” Professor Crawley said. “The longer and more protracted the journey is, the more likely it is people move out of those categories and then back into them.”

She gave the examples of Syrian refugees who were not directly affected by the war but fled because their livelihoods were destroyed, and migrant workers from sub-Saharan Africa caught up in the Libyan conflict.

The report was also critical of moves to prioritise refugees from Syria, and sometimes Iraq, Afghanistan and Eritrea over asylum seekers from other countries, in a possible violation of the 1951 Refugee Convention.

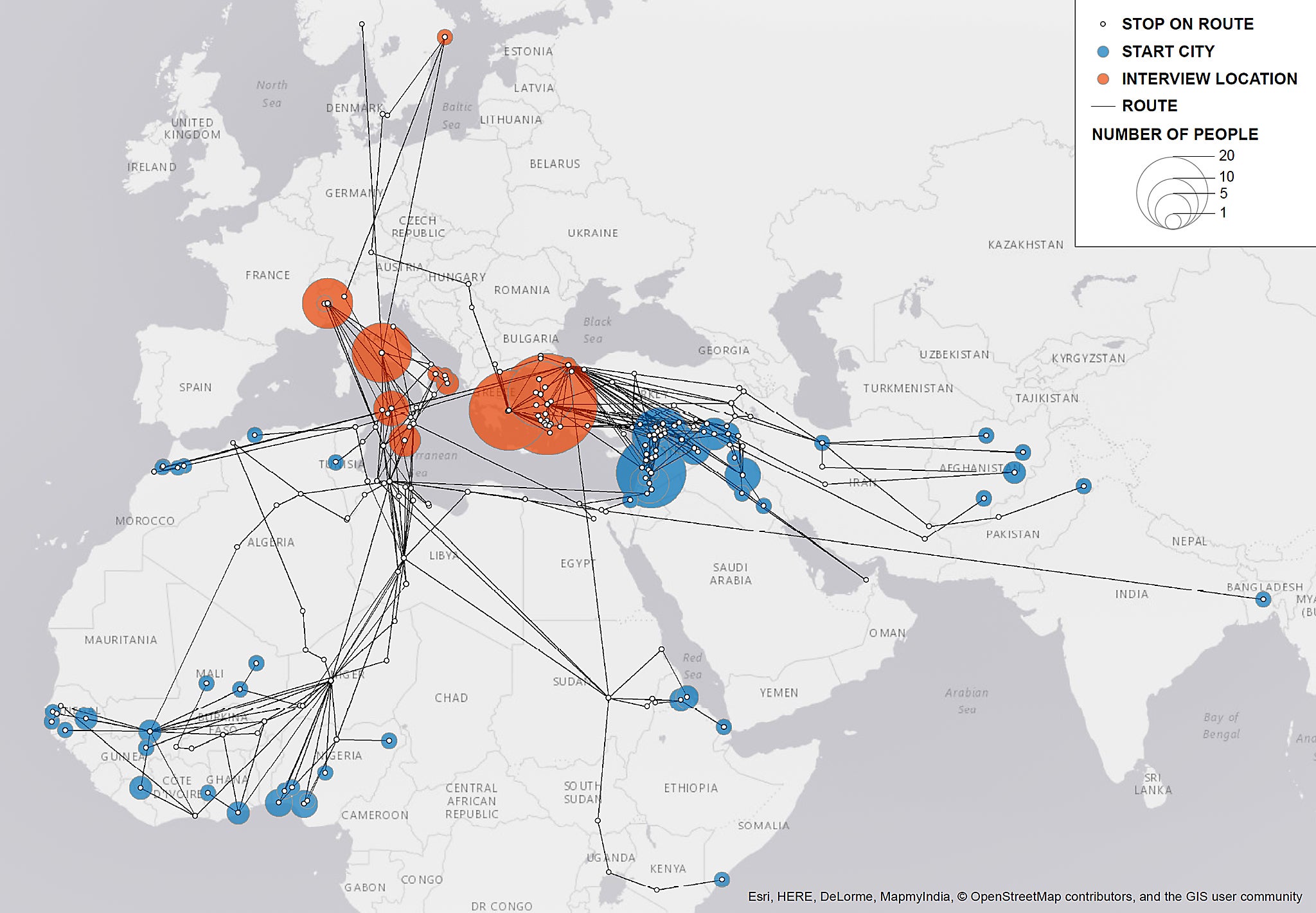

The Medmig project, believed to be one of the largest of its kind, used interviews with more than 500 asylum seekers who crossed the Mediterranean in 2015.

Its report, to be launched at a meeting of European policy makers, international organisations and NGOs in Brussels on Thursday, is a collaboration between the universities of Coventry, Birmingham and Oxford with specialists in Greece, Italy, Turkey and Malta.

“The cause of the flow hasn’t been addressed, smugglers haven’t been addressed, deaths are going up and people who are in Europe are not being integrated as they should be,” Professor Crawley said.

“The response has been an absolute failure.”

A Government spokesperson said the UK has committed more than £2.3 billion to help displaced people in Syria and neighbouring countries and almost £65 million to support humanitarian assistance within Europe.

The Royal Navy also started training the Libyan coastguard in October as part of the EU's Operation Sophia, which sees boats patrolling the Mediterranean tracking smugglers and performing rescues.

“We are clear about our moral responsibility to assist those who are suffering as a result of the migration crisis," the spokesperson said.

"This includes providing financial and practical support in conflict regions, working upstream to stop the most vulnerable making perilous journeys and providing protection to those who need it."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments