Rabbit-hutch Britain: Growing health concerns as UK sets record for smallest properties in Europe

Millions living in overcrowded housing because of failure to build new homes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Britain is in the grip of an invisible housing squeeze with millions of people living in homes that are too small for them, according to new research which reveals that more than half of all dwellings are failing to meet minimum modern standards on size.

The poorest households are being hit hardest, with estimates suggesting that four-fifths of those affected by the Coalition’s “bedroom tax” are already forced to contend with a shortage of space, the Cambridge University study found.

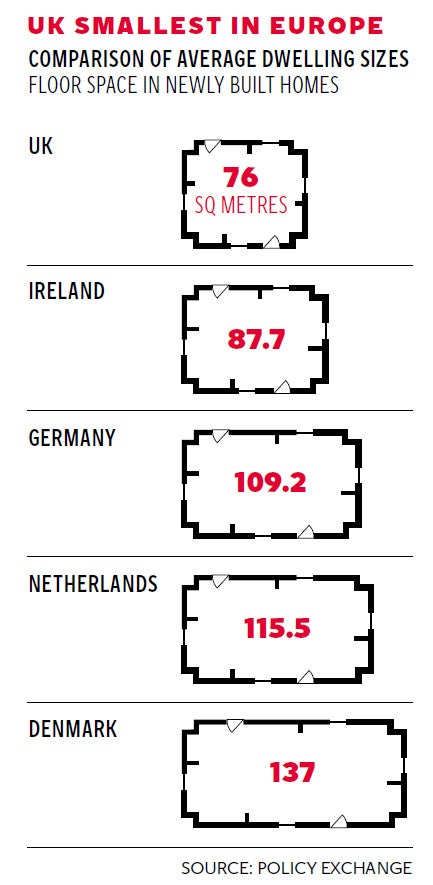

The findings will put pressure on the Government, which announced it was to develop a national space standard – although this will only be enforced where it does not impinge on development. Critics argue that the UK already has the smallest properties in Europe following the end of national guidelines in 1980. But soaring land and property prices and a shortage of new homes are fuelling overcrowding, which causes health problems including depression, insomnia and asthma.

The authors of the study – based on an analysis of 16,000 homes in England – said the findings showed the bedroom tax was “fundamentally flawed”. The study argues that, when analysed by floor space instead of the number of rooms, 55 per cent of all homes fail to meet enhanced minimum guidelines laid down by the London Housing Design Guide. This was introduced by the London Authority in 2011 to improve the quality of accommodation in the capital, but has come to be seen as the industry-wide standard.

When analysed by number of current occupants, one home in five is too small. And the problem of too many undersized properties would be much more serious if it were not for low occupation rates caused by increased numbers of single-person households.

Worst affected were flats and terraced houses with children, whilst the study suggested that 79 per cent of homes were either near or below acceptable size.

The average floor space for a dwelling in the UK as a whole is currently 85 sq metres, whilst new-builds average only 76 sq metres – putting Britain at the bottom of a league table of 15 countries including Ireland, Portugal and Italy.

The paper, in the journal Building Research & Information, said that the extent of the problem was not fully understood. Up to a third of householders were said to be unhappy with where they lived. “The majority of homes in the UK are not fully occupied and yet residents are dissatisfied with the amount of space, with lack of storage space, insufficient space for furniture and lack of space in which to socialise often cited as particular problems,” said the authors Malcolm Morgan and Heather Cruickshank.

Mr Morgan, who led the research, said many people found themselves in what was described as a three-bedroom property but which only had the floor space of a two-bedroom place under the London standards. Box rooms categorised as bedrooms were only of use as storage spaces or studies.

The bedroom tax looks at the number of bedrooms, and not at the total available space per person. But the study found that “only 19 per cent of households losing housing benefit (under the bedroom tax) could be considered to have more space than they needed.”

The president of the Royal Institute of British Architects Stephen Hodder said the average new one-bedroom property measuring just 46 sq metres was the same size as a London Underground carriage. “This is depriving households of the space they need to live comfortably and cohesively,” he said.

“Space for children to do their homework, private areas for rest or relaxation and even space to store food and the vacuum are all major concerns in British homes. With a failing housing market, we need to empower our local authorities to borrow money and build quality homes,” he added.

But the Home Builders Federation said market forces, most particularly the price of land, dictated the cost and size of new homes. Steve Turner, a spokesman, said: “House builders have to provide a choice. There are plenty of large homes available on the market and there are smaller ones to cater for people on a smaller budget. If you say all homes have to be a certain size it will exclude a lot of people.”

Rachel Fisher, head of policy at the National Housing Federation, said: “This is evidence that the bedroom tax is not working. It is not making better use of social housing stock because the imbalance between the distribution of households and homes means that in many parts of the country perfectly usable homes are lying empty.”

A Department for Work and Pensions spokesman said: “The fact is that before our reforms taxpayers were funding 820,000 spare bedrooms in working age households in the social rented sector. The removal of the spare-room subsidy is a fair reform so the taxpayer no longer pays for people’s spare bedrooms, while over 300,000 people continue to live in overcrowded homes and 1.7 million sit on council waiting lists.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments