Poker player loses £7.7 million in winnings after Supreme Court rules he cheated

US gambler Phil Ivey loses case against London casino Crockfords after five-year legal battle

A poker champion has lost a lawsuit against a London casino that refused to pay him millions in winnings because it said he had cheated, in a ruling that overturns 35 years of legal practice on what is “dishonest”.

The ruling means that juries in criminal cases in England will no longer have to consider whether defendants realised that what they did would be seen as dishonest by reasonable, honest people. The question will be whether the conduct was dishonest by those standards, regardless of the defendant’s perception.

“This is one of the most significant decisions in criminal law in a generation,” said Stephen Parkinson, head of criminal litigation at the law firm Kingsley Napley, which advised the casino in the Supreme Court case.

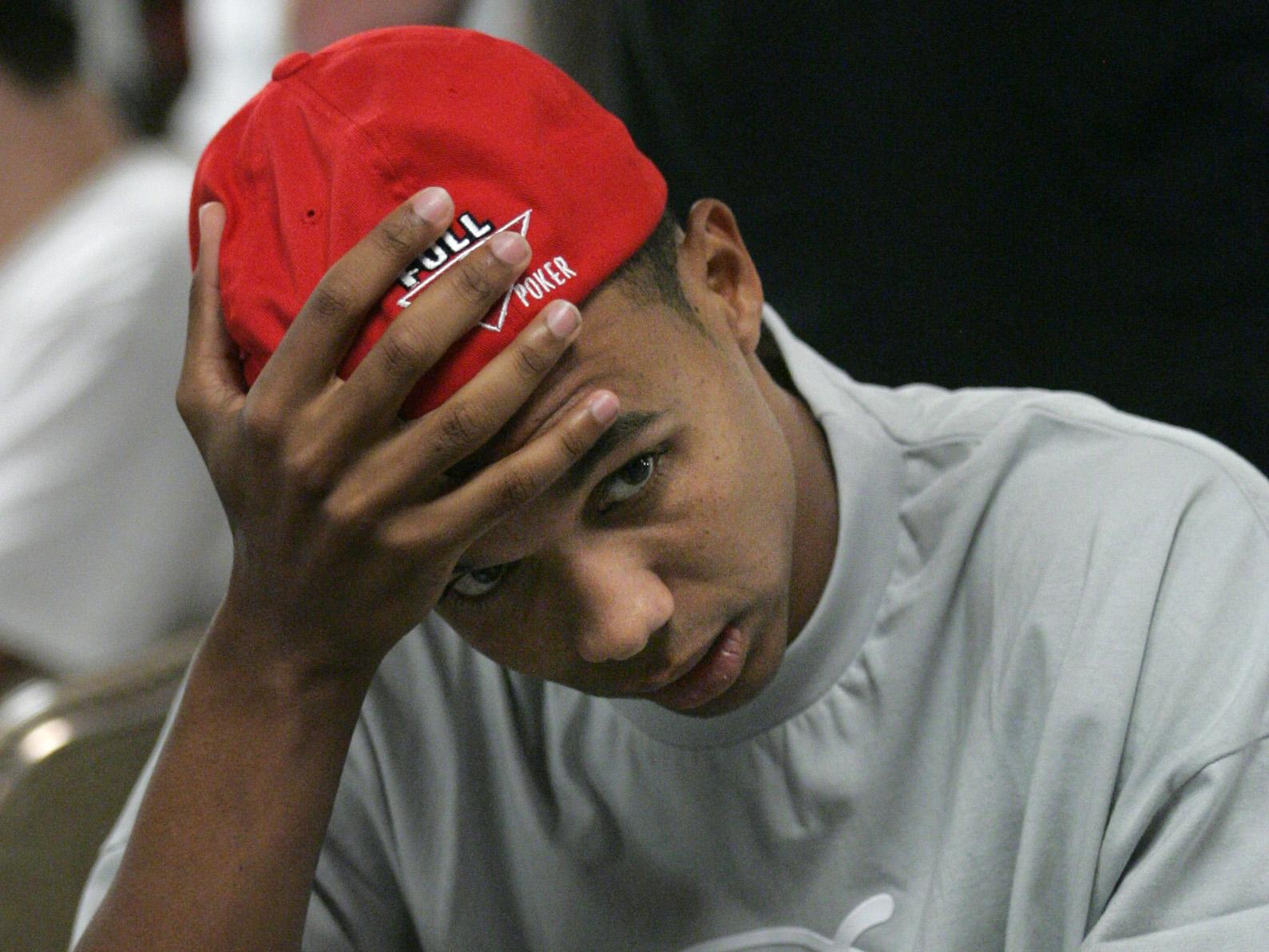

The legal battle, a civil not criminal one, hinged on whether the actions of professional US poker player Phil Ivey during games of Punto Banco at the Crockfords casino in London over two days in August 2012 amounted to cheating.

Crockfords refused to pay Ivey his winnings of £7.7 million on the basis that he had cheated by using a technique known as “edge sorting” while playing the game, a variant of Baccarat that is supposed to depend on luck not skill.

Ivey admitted using edge sorting, which involves spotting tiny differences between the long edges of playing cards to keep track of good ones, but argued this was a legitimate advantage.

As part of his plan, his associate feigned superstition to induce a croupier to turn cards in a particular manner. The croupier had no idea of the significance of what she was doing.

Ivey sued Crockfords for the money, but the London High Court and the Court of Appeal both ruled against him. The Supreme Court upheld the earlier judgements.

“What Mr Ivey did was to stage a carefully planned and executed sting,” it said in its judgement. “That it was clever and skilful, and must have involved remarkably sharp eyes, cannot alter that truth.”

The case led the Supreme Court to legal conclusions that go far beyond the intricacies of card games and will have a profound impact on criminal cases in England and Wales that revolve around whether someone acted dishonestly.

Since a landmark case in 1982, juries have been asked to apply a two-stage test when tackling the dishonesty question.

Firstly, jurors had to ask whether what a defendant did was dishonest by the standards of ordinary people. Then, they had to ask whether the defendant must have realised that their conduct would be seen as dishonest by those standards.

The answer to both questions had to be yes for a defendant to be convicted.

But in the Ivey ruling, the Supreme Court said the second part of the test had the unintended effect that the more warped a defendant’s standards of honesty, the less likely it was that he would be convicted of dishonest behaviour.

It said that the second leg of the test should no longer apply.

This is a momentous change because the two-stage test has been a key element in fraud cases for decades.

For example, it featured heavily in the directions to the jury in the case of Kweku Adoboli, who was convicted of fraud in 2012 over a spate of unhedged trades that cost the Swiss bank UBS $2.3 billion.

Reuters

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks