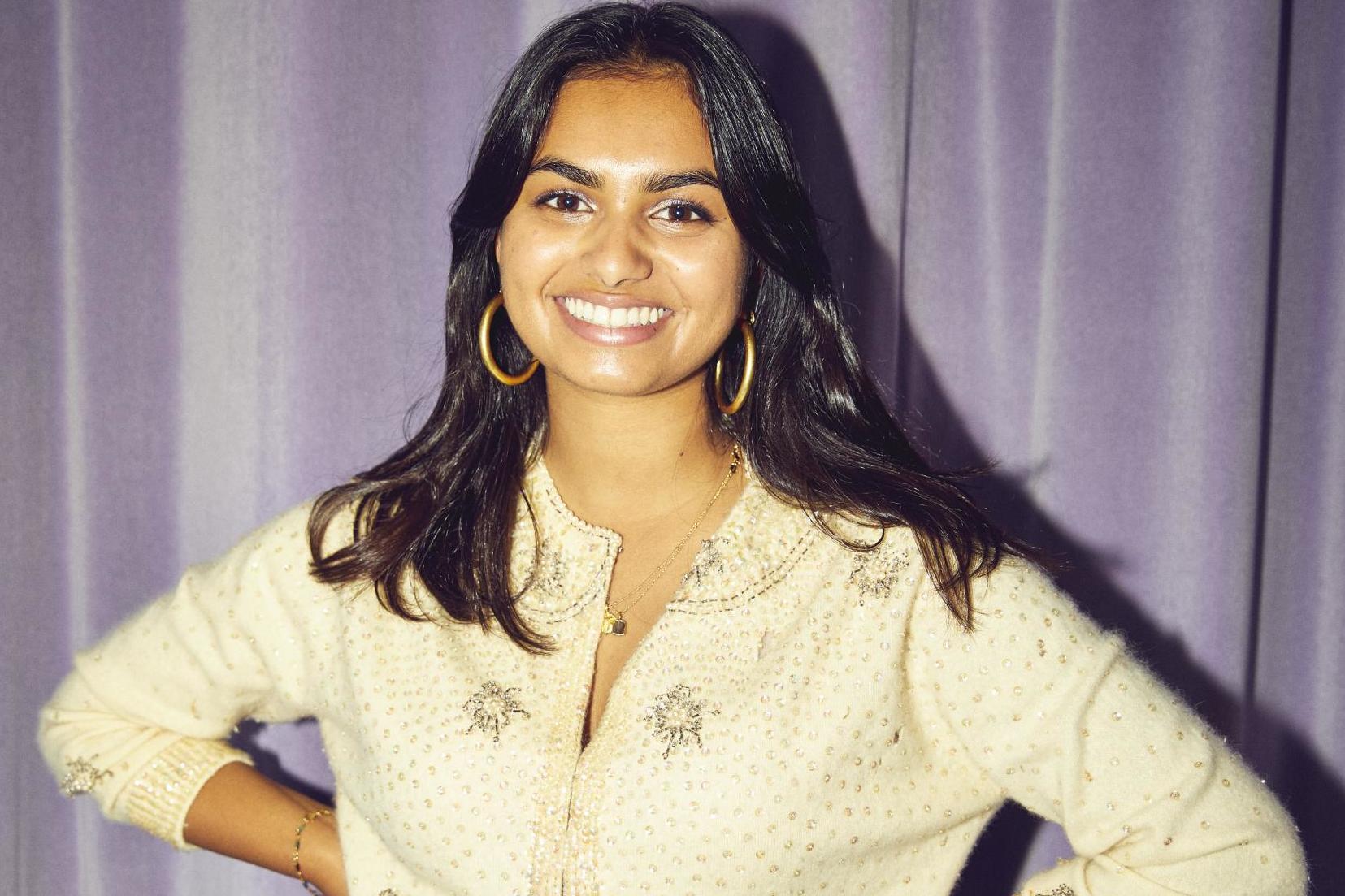

How one teenager’s period poverty campaign has sparked change for schoolgirls across Britain

Amika George says girls have resorted to using rags and sleeves of old T-shirts for periods

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Amika George started campaigning for the government to provide free period products after learning girls were using newspapers, toilet roll and socks to cope with their periods and missing school each month.

The 20-year-old, who launched the Free Periods campaign in 2017, initially found the government ignored her efforts to fund the free provision of menstrual products in all schools and sixth form colleges.

“I was really disgusted to hear there were girls in the UK who were missing up to a week of school every month,” Ms George, who was 17 when she began the campaign, told The Independent. “I was horrified and really angry that even though it was being publicised, the government did not respond.”

The campaigner resorted to working with a law firm to build a “robust legal case” which argued the government had a legal obligation to provide period products under the Equality Act.

Period poverty is a widespread issue in the UK — with 49 per cent of girls having missed a day of school due to periods and one in 10 women aged 14 to 21 not able to afford period products.

Last spring, the government announced girls at primary and secondary schools in England and Wales would be provided with free sanitary products from early 2020.

The government backtracked and rolled out the scheme to a wider age range — also including those in sixth form colleges — after it came under fierce criticism from campaigners for initially only choosing to distribute period products in secondary schools.

Ms George applauded the government scheme but raised concerns schools might not take up the offer of providing sanitary products due to not being aware they are accessible.

“I am really, really excited they will be freely available from next week,” she added. “The really important thing is the schools take up the government on it. We are pushing for all schools to get involved. Access to period products should be categorised as a basic necessity in the same way that toilet paper and soap are, and tampons and pads should not be classed as a luxury item.”

Sanitary products in the UK are classed as a “luxury, non-essential item” and taxed at 5 per cent — with the average lifetime cost of sanitary products estimated at £4,800.

Ms George said lots of friends and strangers had contacted her to recount their own experiences of period poverty.

She added: “Some would say they had got really behind on work and missed huge chunks of the curriculum because of not being able to afford sanitary items. One girl searched in nooks and crannies to find spare change. A lot of the time the girls are too embarrassed, because of stigma and shame, to ask their parents. They do not want to put their parents in the situation of saying: ‘It is food or stuff for your period and we have to prioritise food’.”

The campaigner said teachers had told her they had been forced to spend their own money on buying period products for pupils after noticing the same girls were missing school each month.

She said she had heard from girls who had resorted to using rags and sleeves of old T-shirts for their periods due to not being able to afford proper menstrual products. Women and girls who are faced with period poverty are at risk of a potentially fatal bacterial infection called toxic shock syndrome, Ms George added.

She argued a significant reason why period poverty remains unaddressed is due to the stigma and taboo that surrounds periods.

“Women stick tampons up their sleeves from a young age,” Ms George added. “It is culturally ingrained for us to stay quiet about them. We have been consciously taught periods are shameful and embarrassing and should be a silent topic. Seeing products in schools will encourage children to immediately start conversations about products and around periods.”

The activist said she had encountered backlash from trolls since starting her campaign — explaining men sometimes get angry she is talking about periods publicly and insist period poverty is not a real issue.

She added: “They say ‘periods are disgusting, you are a typical teenager who wants the government to pay for everything’. They sometimes also wrongly make the assumption parents can’t afford products because they are spending money on alcohol and cigarettes.”

Ms George said she hoped to launch a Europe-wide campaign to make schools across the continent follow suit and offer free sanitary products.

Women who have experienced period poverty are more likely to experience anxiety or depression and find it difficult to afford their bills, studies have found.

Lucy Cannon, a PE teacher at John Cabot Academy in Bristol, said girls were missing whole days of education until the school started offering free products in conjunction with a scheme called the Red Box Project.

She said: “They weren’t prepared so would leak in a lesson, go home and rarely come back. Or, they were simply too scared to come into school without any products. Since introducing the red box, one girl said to me: ‘I can be a child again, I can run around at lunchtime without worrying; before, I only had one pad to last all day so was always worried about leaking.’

“Offering free products also normalises the dialogue around periods. Everyone in school now talks openly and positively about periods — including the boys. The government’s funding should have happened years ago: nothing has changed, we’ve always been women, it’s just now people are listening!”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments