‘I did 12 years in jail from the age of 16. Now I’m a reformed man helping young offenders – and the government is trying to deport me’

After witnessing his aunt gunned down in Jamaica at the age of nine, Paul Douglas was sent by his family to the UK where he flourished until getting dragged into a gang dispute that forced violence back into his life

“When they said I was going to be on that flight, I closed my eyes and could see my aunty dropping to the floor. I felt like I was there again... And I wanted to die. I wanted to die.”

Paul Douglas had been in Colnbrook removal centre for a matter of days when he was ordered to pack up to get on a charter flight. The words set him into panic mode. He locked his door and began to cut his wrists. All he could see was the vision of his aunt getting shot dead in the street 20 years before – after she too was deported back to Jamaica.

The officers eventually broke into the 30-year-old’s cell and found him unconscious in a pool of blood. Instead of being driven to the flight on 4 February, he was rushed to hospital where he got 22 stitches. After several days, he was discharged and taken straight back to detention – where he is still subject to removal.

Paul was just nine when he witnessed his aunt’s murder. With neither of his parents around, she had been his main carer until she was forced to flee to England after becoming a target of the gang warfare that dominated their local area. But the Home Office refused her asylum claim and sent her back – and days after returning she was shot dead.

Growing up in a Kingston neighbourhood with one of the highest crime rates on the island, death was nothing new to Paul. “On the way to school I’d see dead bodies,” he recalls. “You’d hear gunshots but you became immune to it. When you’re living in and around it, you find a way. I learned to close my eyes and pretend I was in a better place.”

But the murder of his aunt was the wakeup call for his relatives – and when their home was shot at weeks after the murder, they decided to place Paul on a flight destined for the UK.

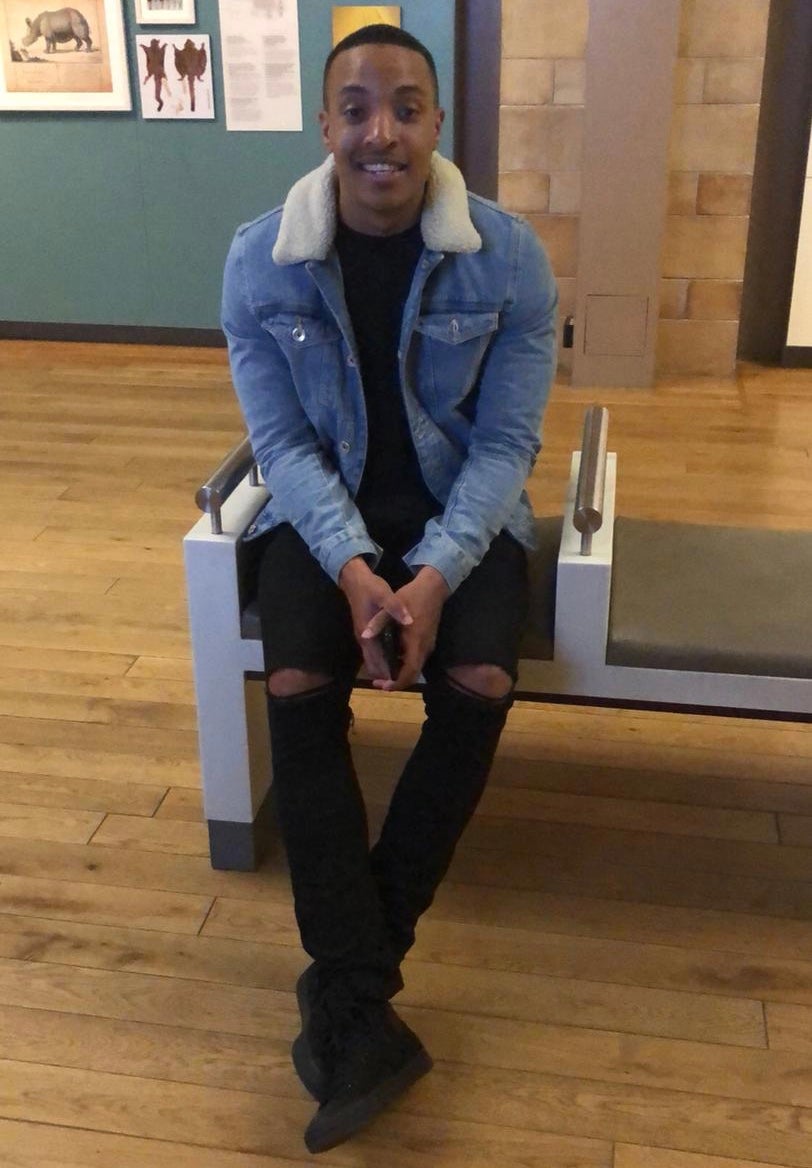

Despite the painful memories, Paul quickly settled into life in London and began to flourish, excelling academically and seizing on opportunities to learn. He achieved good grades in his GCSEs and was planning to study engineering at college.

At the age of 16, though, he was wrenched back to the violence and death he witnessed in his formative years. An altercation with another teenager that began at school – which Paul says he had not wanted to take part in – escalated into a street fight between two groups. During the fracas, a 16-year-old was fatally stabbed.

The judge acknowledged Paul did not strike the fatal blow, but the jury decided he and two other boys were jointly responsible. Paul was sentenced to 12 years in jail for “joint enterprise”.

“We went from aspiring young boys to black boys in a gang,” he says. “There was a lot of talk of gang culture during the trial. That was the last thing I wanted.

“Coming from such a violent place, I always used to say when I was growing up that I never wanted to be like the people I grew up around. I tried so hard. I never engaged in violence. Up until this point I had never been arrested. I was trying to get somewhere in my life.”

Despite the devastation and anger that came with knowing he would be spending the rest of his youth and much of his early adulthood in jail, Paul’s empathy for the victim’s family helped him come to terms with his fate.

“Regardless of the situation, someone lost their life,” he says. “I had to think about the boy’s family – a mum, a dad, sisters, brothers. They were suffering. I had to put myself in their position to understand. In this situation there were no winners.”

He decided to try to take a positive approach to prison, continuing his education behind bars as well as successfully engaging in rehabilitation programmes and acting as a mentor for younger inmates.

“There was a lot of emotion. At the time I was young. You just see your future disappear. I knew I wouldn’t be able to experience a lot of things that young people my age did. I was angry at the system, but I found that that got me nowhere. I couldn’t argue against it. You have to learn to just get on with it.”

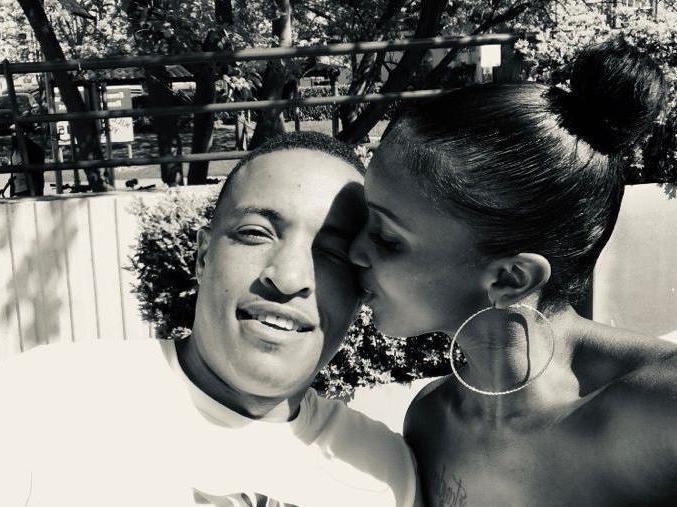

Fourteen years on, after completing his sentence with a glowing report from the parole board, Paul was setting up a home to share with his pregnant girlfriend, Chanel Gebon, in time for the birth of their first child.

But his long-awaited freedom was cut short when he was detained by the Home Office for the first time on the day he was supposed to be attending his unborn daughter’s ultrasound scan. He was taken to Colnbrook, where he was later told he was to be deported to Jamaica.

Chanel, 28, who is a British national, says losing Paul just before giving birth pushed her into a “dark place”. A week or so after he was detained, she went into labour.

“It was something we’d always been talking about, how the birth would be. We were really looking forward to the moment,” she says. “But I had to do it all without him – just hearing his voice on the end of the phone. It was horrible.

“Everything we had planned was positive. Paul isn’t someone who would want to hurt or upset anyone at all. From the moment he came out, he’s been supportive to so many people. He’s done his time. He’s a lot more mature now – he has goals. Everyone deserves a second chance.”

Her words are echoed by Sonya Russo, director of offender behaviour programme Plan B, who worked with Paul during his jail term until the present day, and was on the phone to him while he was self-harming in his cell after hearing about the charter flight. She says the 30-year-old is an “absolute asset” to the community.

“Paul has turned things around and survived a 12-year sentence,” Sonya adds. “He has a big impact in the work we do, because he’s obviously relatable to the boys that we teach. What’s happening to him is just awful. Especially his current condition.”

Volunteering with the charity, Paul has supported young men who have been released from jail, helped them settle back into the community, and advised prison governors about the best way of teaching inmates – as well as working with child victims of the Grenfell Tower fire.

“We’ve got a full-time job for him as soon as we’re allowed to employ him,” says Sonya. “He settled into a new life after prison and then boom, he’s back in these conditions again – it’s like he’s gone full circle. Since he was a small child he’s had it rough, and he’s losing hope that he’s ever going to be OK.”

Despite initial claims by the home secretary, Sajid Javid, that deportees were all guilty of “very serious crimes” such as murder and rape, Paul was among a minority of them who had actually been convicted of such an offence.

But even in his case the facts point to a more complex story. The 30-year-old is reduced to tears when he talks about his threat of deportation.

“Everything was good. I was finally getting the opportunity to almost live my life. To be suddenly picked up like this and be in this position, I’m mindblown,” says Paul. “I got released by a High Court judge. The judge deemed me not a risk to the public. I walked out of prison with my bags on my back.

“Working with young offenders made me feel some kind of purpose. I changed some kids’ lives dramatically after speaking to them. But they just look at what’s on paper. They say they need to protect the public because this person is very dangerous, but they don’t look at the facts. No one wants to listen.”

Harking back to his aunt’s murder, which came flooding back to him when immigration officers came to put him on a flight back to Jamaica, leading him to cut his wrists, Paul says openly: “That wasn’t self-harm. I wanted to kill myself.

“The Home Office was told my aunty was at risk of death, but they removed her and allowed it to happen. Now I am in the same position, showing them all the records and everything. It’s like there are no lessons learned.”

A Home Office spokesperson said: “Mr Douglas has no legal right to remain in the UK and has been convicted of murder.

“The law requires that we seek to deport foreign nationals who abuse our hospitality by committing crimes in the UK. This ensures we keep the public safe.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments