How the Parler takedown has dealt another blow to the British far right

At one point, extremists such as Tommy Robinson and Britain First had a significant presence on social media. But the latest shutdown shows how deplatforming has fragmented their audiences and left them struggling to gain followers, writes Lizzie Dearden

The shutdown of social media network Parler in the wake of the storming of the US Capitol sent reverberations through the online world of Donald Trump supporters this week. But it also left the British far right scrambling to save its audiences – the app was among a cluster of niche social networks that extremists have been forced to rely on after bans by Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.

From a high of 1 million Facebook subscribers and 413,000 Twitter followers, English Defence League (EDL) co-founder Tommy Robinson has now – with the loss of 290,000 Parler followers – been left with a total of fewer than 100,000 followers on social media.

Analysis seen by The Independent as part of our Supporter Programme investigation into the rise and fall of Britain’s far-right figureheads shows how rapidly the online followings of extremists have diminished – and with it, their influence.

Billions of views

In 2018, Robinson’s Facebook page was getting between 5 million and 10.8 million visits every month. His posts garnered almost 1.5 billion impressions – appearances on people’s screens – in the year. At the time, he also had 413,000 followers on Twitter and 359,000 subscribers on YouTube.

Such was his reach on social media that in May that year, a court heard it was “inconceivable” that jurors in a British grooming gang trial would not have seen one of his videos.

The footage, streamed live on Facebook from outside Leeds Crown Court, had been viewed 3.5 million times by the time that defence lawyers applied to dismiss the jury four days later. Robinson, who acknowledged on camera that there were reporting restrictions on the case, broadcast for more than an hour about “rape jihad gangs”.

A barrister argued that even if jurors had not seen the video, which risked prejudicing them against the defendants, it was “inconceivable” that they had not been alerted by other members of the public.

A judge rejected the application, and the rapists and sex abusers in the gang were found guilty and jailed, but the Facebook post came close to collapsing the case.

And Robinson was not alone among the UK’s far right in having such an extraordinary online reach.

The Independent’s Supporter Programme funds special reports and investigations from an award-winning newsroom you can trust. Please consider a contribution

Britain First had more than 2 million likes on its Facebook page by the time it was deleted in March 2018, with another 29,700 followers on Twitter and more for individual accounts run by then-leaders Paul Golding and Jayda Fransen.

Fransen’s tweets had fallen into the sights of Donald Trump, who shared them to a global audience of tens of millions in late 2017.

Other far-right groups were also commanding huge audiences. The British National Party (BNP) had 214,000 Facebook followers and the EDL had 21,000 on its page after Robinson’s departure.

Individuals espousing extreme views were also able to enjoy significant online success, such as British YouTuber Paul Joseph Watson (almost 1 million Facebook followers) and Katie Hopkins (1.1 million Twitter followers).

Move to deplatforming

But after years of campaigning by counter-extremism organisations, the tables started to turn.

Facebook, Twitter and YouTube have been deleting prominent far-right accounts in waves of takedowns over the past three years, causing the most prolific pages to disappear.

Robinson, Britain First, the BNP, EDL, National Front and pan-European white nationalist group Generation Identity were among those hit.

Characterising the moves as “censorship”, leading figures vowed to rebuild their audiences on alternative platforms, but they have so far failed.

Some have moved to smaller platforms, such as the messaging services Discord and Telegram, in attempts to co-opt them for their audiences, while others have pulled followers to newer sites that court a right-wing audience.

Parler, which functions similarly to Twitter, became a favoured alternative after gaining high-profile American users, including conspiracy theorist Alex Jones.

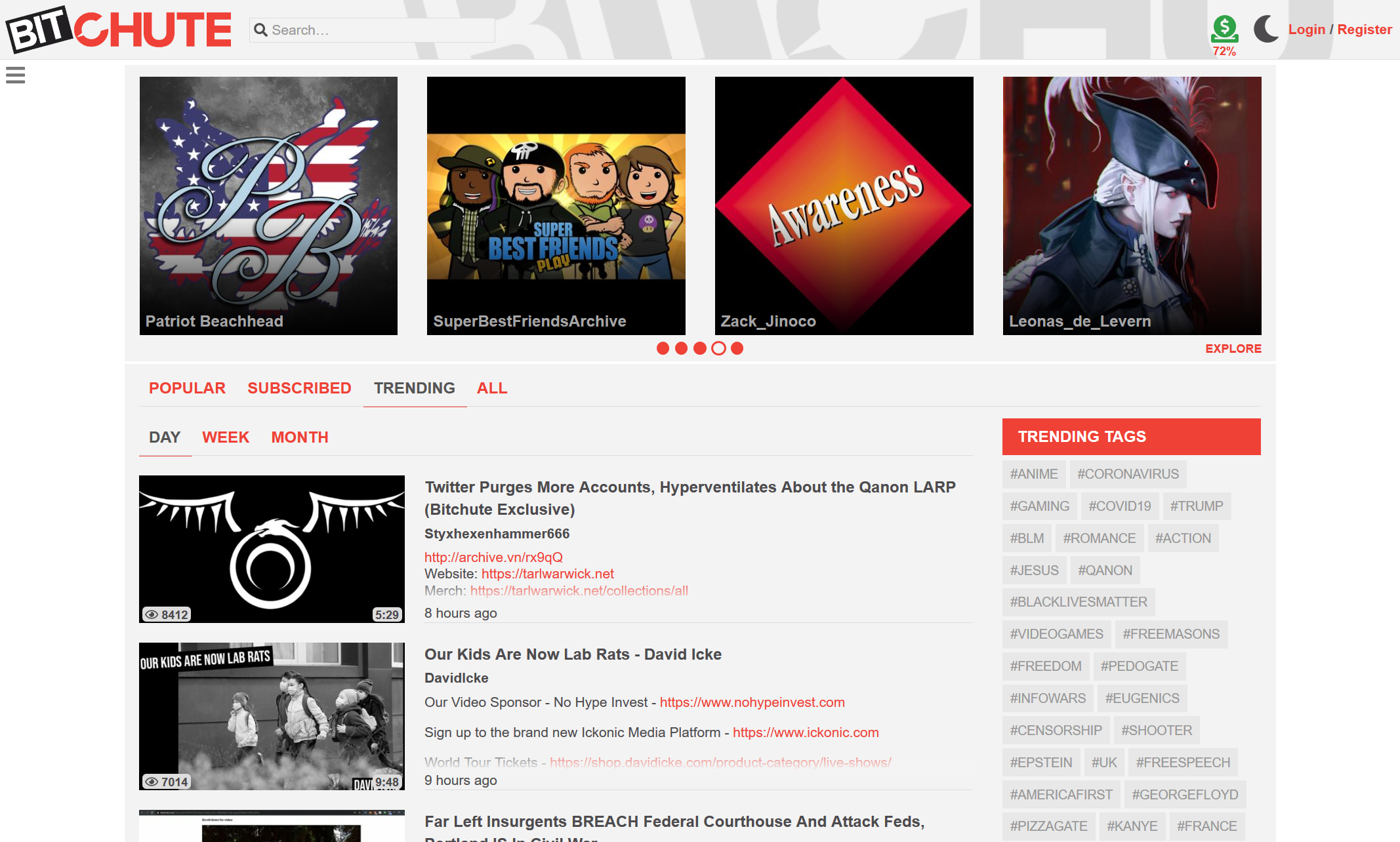

The Russian Facebook equivalent VK, video site BitChute and encrypted messaging app Telegram have also been widely used by British extremists deleted from mainstream networks.

But none, either alone or combined, have reached the audience numbers that high-profile figures enjoyed before the takedowns.

“If they continue to split themselves across a series of platforms, none of them will become viable in the long term,” Joe Mulhall, a senior researcher at counter-extremism organisation Hope Not Hate, told The Independent.

Read more from our Supporter Programme here

“The question is whether this wave of deplatforming is enough to create a genuine existential crisis in the far right that causes a level of organisation to co-opt or build a single platform.”

Mr Mulhall said deplatforming had caused a “rapid drop-off” in the number of people attending extremist events and protests, even before the coronavirus pandemic.

“In the past 18 months the social media climate has changed and things are moving quicker – it has had a huge impact,” he added. “The combination of external pressure and internal changes is having an effect.

“It has extraordinarily reduced extremists’ reach and that has been reflected in offline activism as well.”

Mr Mulhall said that while deplatforming risks creating increasingly extreme “silos” in less regulated online spaces, it reduces the ability to reach new followers.

Robinson had managed to amass almost 290,000 followers on Parler, and had about 14,000 on VK before the account was removed in December. He has about 59,000 on Telegram and 27,000 on Bitchute – a total that is significantly lower than on mainstream social networks before the deletions.

Britain First has 18,500 followers on Telegram, and had 16,000 on VK and a similar number on Parler – far down on its previous 2 million Facebook followers.

Mainstream platforms have not coordinated the takedowns and some extremists, such as former BNP leader Nick Griffin and Anne Marie Waters, leader of the For Britain group, have managed to remain on some social networks despite being removed from others.

Capitol takedown

The takedown of Parler caught Robinson and other extremists unawares, sparking a panicked flurry of discussions in chat groups about where to congregate instead.

Many were calling on followers to use Telegram and “free speech” social network Gab.

“Please spread the word that we are back here on Telegram, tell all our patriot cousins from across the pond we are here still fighting the good fight,” Robinson told his followers on Monday.

In the same post, he admitted he had lost access to a Gab account with 29,000 followers.

Paul Golding, the leader of Britain First, bemoaned that “hardly any of the new users flooding platforms like Gab and Telegram are from the UK”.

He called for supporters to “think of a way to prompt UK users on to these platforms too”.

Parler’s operators have launched legal action in the US to get back online, arguing that Amazon had abused its market power by withdrawing web-hosting services following the storming of the US Capitol.

Mr Mulhall said the bulk of British far-right extremists were on Telegram but that some of the “more extreme elements” were heading to Gab, where overt white supremacy and antisemitism is rife.

“The fact is that none of those platforms will manage to attract non-far-right people,” he said. “Parler had a chance but it won’t now.

“The ability to bring in the day trippers of the far right rather than core activists has been reduced and that is really important,” he added, saying it was much harder to accidentally stumble across extremist content on the likes of Telegram than it was before the takedowns by Facebook and Twitter.

“It’s really positive because on mainstream platforms the major threat is the ability to reach victims and do harm, but also to recruit and propagandise and reach large audiences.

“Those things decrease on those other platforms because there are far fewer normal people to win over and target.”

Mr Mulhall said the takedowns had also damaged extremist financing by hitting their ability to gain income from merchandise sales, donation campaigns and YouTube monetisation.

While the far right commonly characterises the curbs as an attack on free speech, Mr Mulhall believes that their ability to run rampant on social media will be viewed historically as a “bubble”.

But he warned that deplatforming was not a “silver bullet” for extremism, and that action had been late, inconsistent and uncoordinated.

“The Capitol is the perfect example of the real-world effect of what social media companies have refused to deal with,” he said. “I would love this to be a learning moment.”

VK accounts used by Robinson and Britain First were removed after The Independent sent a request for comment. “We have blocked these communities for spreading hate speech and we will closely monitor the situation and check for violations and other communities with such content,” a spokesperson said.

Ray Vahey, the founder and chief executive of BitChute, said it was politically neutral and regulated by Ofcom.

“We treat all users as equals with the same rights, and we openly welcome all forms of diversity,” he said.

“Our guidelines are intended to prohibit illegal content and unacceptable behaviour that leads to oppression and incitement. We endeavour to enforce our guidelines in a way that is fair, transparent, and does not infringe on the right to freedom of expression or the ability to hold power to account.”

YouTube said that it removes channels and videos that violate its policies on hateful or abusive conduct and those linked to banned groups.

An update to its guidelines resulted in many popular supremacist channels being terminated over the past year, YouTube added.

Videos containing “controversial” religious or extremist content falling short of a violation are placed under restrictions and not able to monetise.

Twitter said it had suspended more than 70,000 accounts associated with the far-right QAnon conspiracy and was taking action against online behaviour “that has the potential to lead to offline harm”.

Facebook said it had a programme to ban “dangerous individuals and organisations” and had removed more than 250 white supremacist organisations from Facebook and Instagram.

Parler and Telegram did not respond to The Independent’s request for comment.

The image accompanying this article was changed on 3 March, 2021

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks