‘A tale of triumph and tragedy’: Calls for black Victorian circus owner to be included in national curriculum

Norwich-born Pablo Fanque was unrivalled showman who put on some of era’s grandest spectacles, but died near penniless

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.He was one of 19th-century England’s most famous circus owners and greatest showmen.

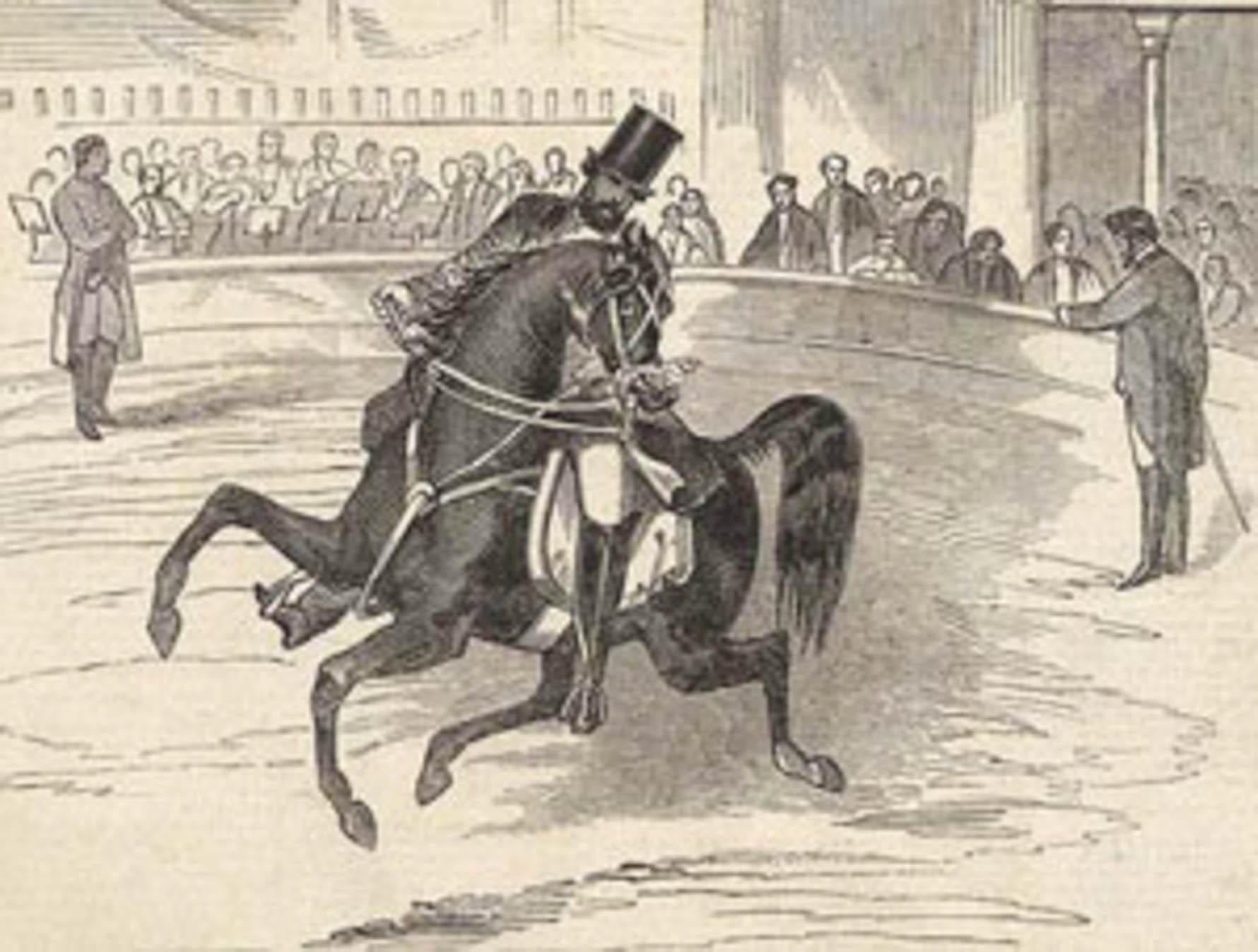

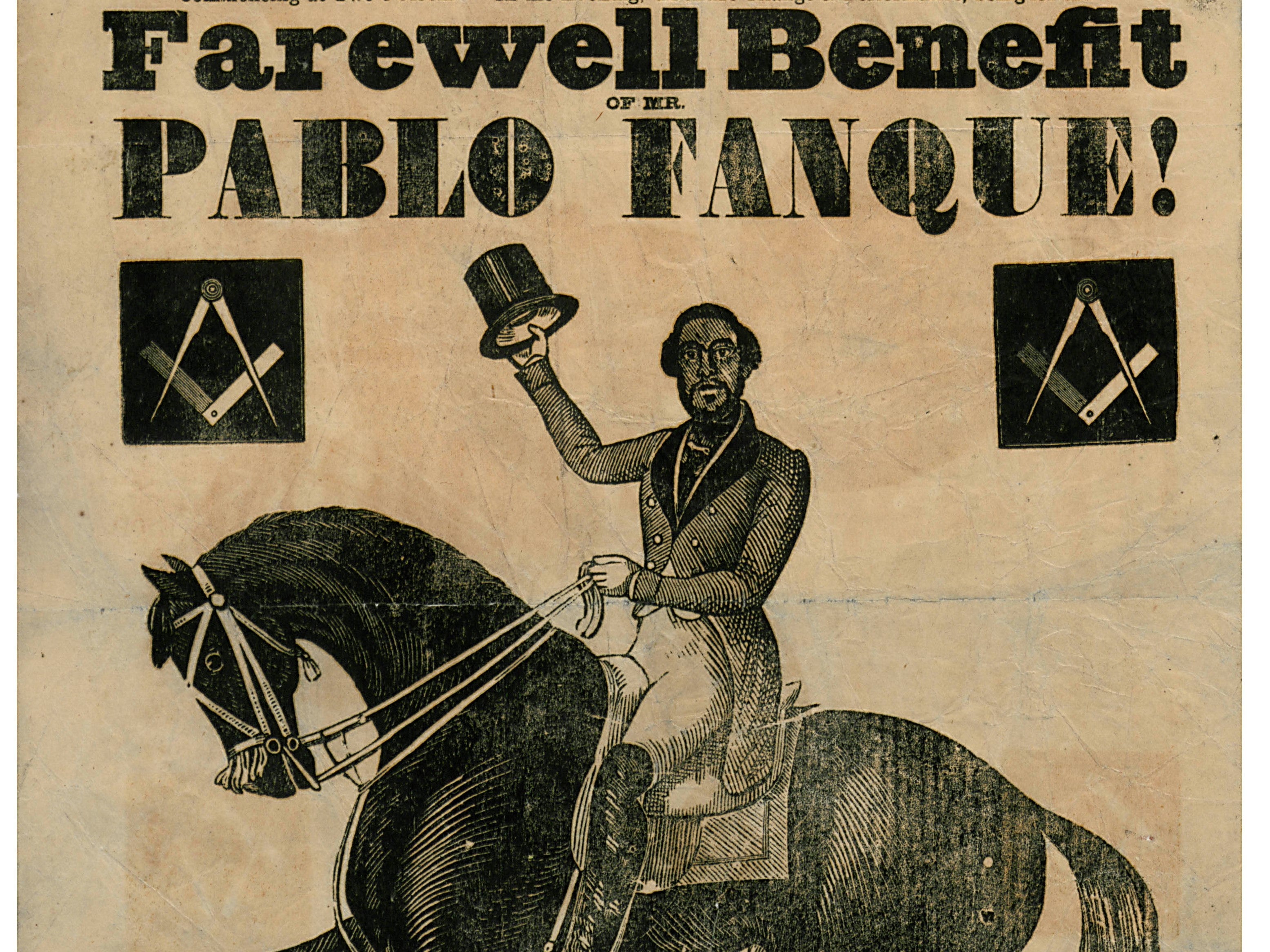

Pablo Fanque put on some of the era’s most lavish spectacles in some of its grandest big tops. As an acrobat and horse handler, he was considered unrivalled. “We have never seen his skills in equestrian surpassed or equalled,” wrote the Illustrated London News in 1847.

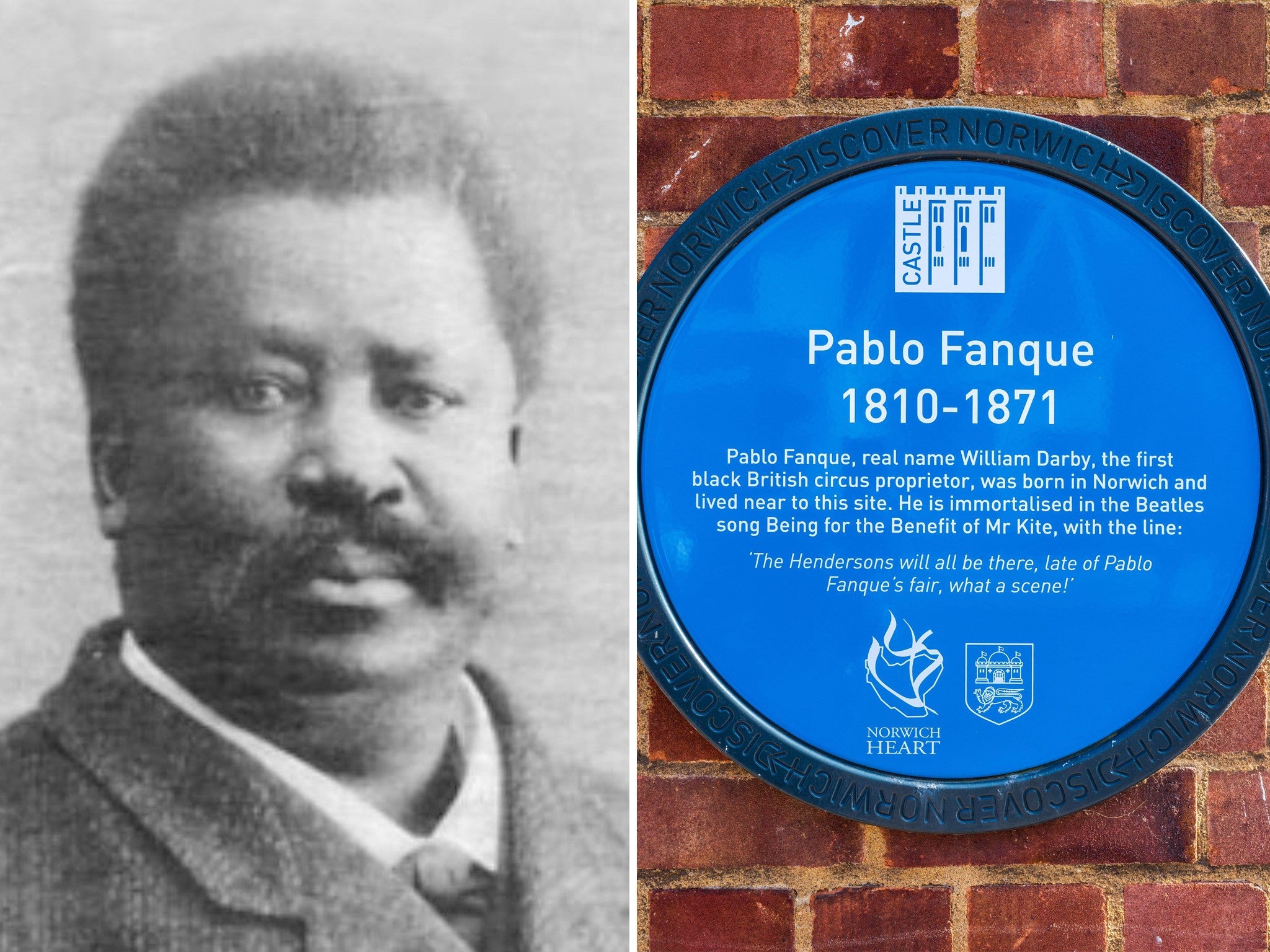

So loved was this entertainer, that when he died in 1871 thousands of people lined the streets of Leeds for his funeral. Almost a century later, he would be name-checked in the Beatles song “Being For The Benefit Of Mr Kite!”

Yet there was something else notable about Fanque’s success in Victorian Britain: he was a man of colour.

The Norwich-born performer – thought to be the son of an African or Caribbean servant and an English mother – was the world’s first black circus owner.

Now, as Black History Month begins, a string of top academics are calling for his remarkable life to be included in the national curriculum.

They reckon that his story should be used as a vivid and engaging starting point for a new syllabus area exploring the oft-ignored diversity of working-class British history.

“Fanque’s life was absolutely fascinating,” says Dr Richard Maguire, senior lecturer in history at the University of East Anglia and leader of a new research group reviewing how black history could be better integrated into the syllabus. “His story is one full of triumph and tragedy, and I think that would make it very appealing to young people. But he is also just one example of the rich diversity that has been inherent in British communities dating back at least to the mediaeval period.”

By ignoring such people, the current curriculum offers an incomplete picture of the national past, it is argued. Correcting this, so the theory goes, would not only help boost the attainment of today’s pupils of colour, it could also help reduce future institutional racism by broadening our collective understanding of the country’s heritage.

Wait. All that from a circus lad?

Certainly so, says Vanessa Toulmin, a professor in entertainment history at the University of Sheffield who has spent years researching Fanque and who is backing the new calls.

“This is somebody who overcome huge barriers and prejudice to become an amazing innovator and performer in his field,” she says. “He is just an inspiring person to learn and to know about, while also giving us a greater understanding of the multiplicity of our heritage.”

Unquestionably, Fanque’s life was quite something.

Herein was fame, acclaim and, at one point, a show that included a woman dancing on horses while wearing a “full bloomer costume”. He himself was described as the “loftiest [horse] jumper in England”; while his travelling big tops – which he took across England, Scotland and Ireland – were famed for bright colours, decadent chandeliers and tiered seating.

But there was devastation as well as distinction: in 1848, his first wife, Susannah, died after a wooden amphitheatre collapsed during a performance in Leeds. Pertinently, despite a lifetime of accolades, this circus king would die a virtual pauper, passing away in the rented room of a Stockport inn.

“It’s very sad,” says Toulmin, “because this is someone who had spent his career bringing joy to others.”

Fanque was born William Darby in 1810 in a Norwich workhouse (a halls of residence in the city is today named after him).

While details about his childhood are few and far between, we know that, by the age of 11, he was an orphan living and working with Batty’s travelling circus. There, over two decades, he became a crowd favourite renowned for his equestrian skills and tightrope walking. At 31, he struck out on a new venture, setting up his own touring company with his great friend, the clown William Wallet.

Exactly how much discrimination he faced remains something of an unknown. In more than 300 newspaper articles collated by Toulmin, she says only three refer his colour – and those only incidentally. Far more often, they are glowing in their praise. He married two white women and fathered six children with no apparent scandal.

Yet, as someone whose career dovetailed with both the tail end of slavery and the earliest beginnings of the colonial “Scramble for Africa”, it seems unthinkable he would not have faced some prejudice.

One telling anecdote in Wallet’s 1870 autobiography recalls how, during a day off fishing in Oxford, a student had become convinced Fanque’s success on the river was somehow down to his “complexion”. The next morning, Wallet writes, “we were astonished to find the experimental philosophical angler with his face blacked after the most approved style of the Christy Minstrels.”

It is not noted how Fanque reacted.

“It seems unlikely that he would not have had to face some discrimination,” says Maguire. “But it is difficult to speculate how this would have played out because none of the primary material really touches on it. There are no existing interviews with Fanque. To some extent it has to be conjecture.”

Whatever the obstacles, his own company continued performing, in one guise or another, for the best part of three decades. “Such is Mr Pablo Fanque’s character for probity and respectability, that wherever he has been once he can go again,” noted the Blackburn Standard during one of his stints in the town.

He died in 1871, aged just 61, while living with his second wife, Elizabeth Corker – herself the daughter of a circus performer.

By then, the couple had fallen into poverty – a fate that, while seemingly unjust, was not altogether uncommon. Such performers lived their lives on a financial knife edge in Victorian Britain. Most eventually fell off.

Yet, rich or not, Fanque’s reputation as one of the era’s great showmen had been secured.

After he was buried in Leeds – in a plot next to his first wife – the chaplain of the Showman’s Guild would pay a fitting tribute. “In the great brotherhood of the equestrian world there is no colour line,” he wrote. “The camaraderie of the ring has but one test: ability.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments