UK at ‘forefront of new frontier’ for holy grail of clean energy

UK plans to build world’s first nuclear fusion-powered plant by 2040

Britain has an opportunity to be at the forefront of a new clean energy “frontier” with the launch of the world’s first nuclear fusion-powered plant, a senior official has said.

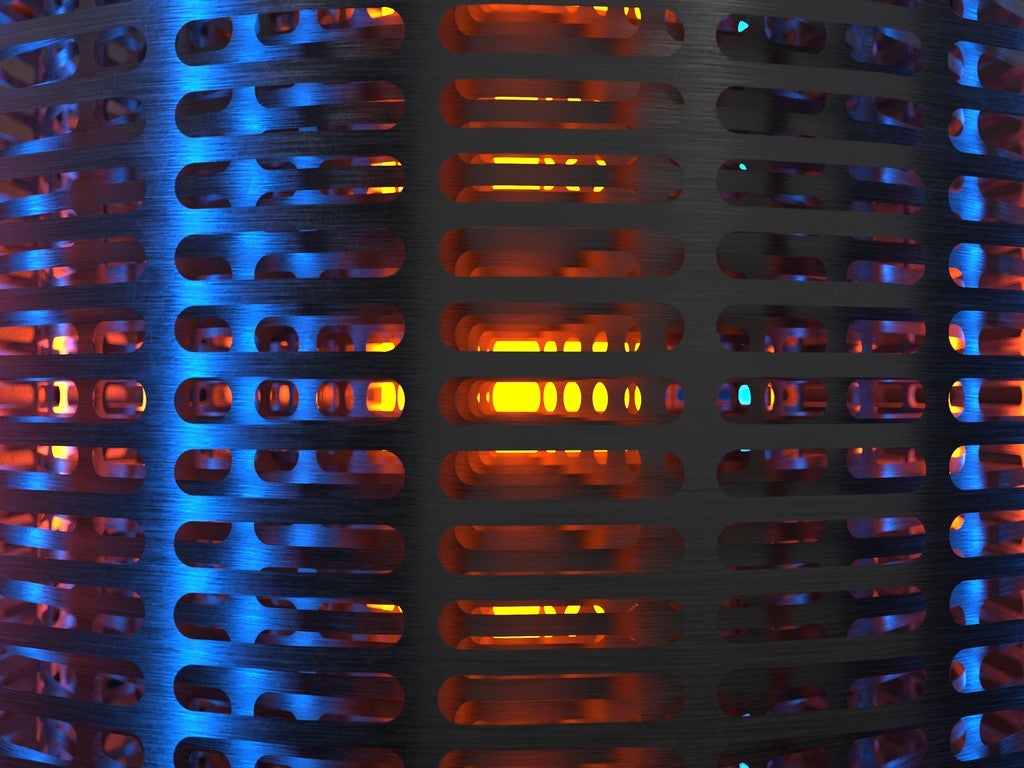

Government scientists at the UK Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA) are working on plans to deliver clean power through the world’s first compact fusion reactor by 2040.

Nuclear fusion has been heralded as the “holy grail” of renewables although the technology to deliver it remains in its infancy and needs further development,

Ministers set up the Spherical Tokamak for Energy Production (Step) programme to accelerate research in the area.

“Step is fusion’s Apollo,” Paul Methven, UKAEA director, told the Telegraph as he compared the programme to the US’s 1969 mission to the moon.

Step is a government programme that has been given £222 million in funding and tasked with designing and constructing the world’s first fusion power plant by 2040.

“We are currently designing the rocket and building the team, across both public and private sectors, that will put our equivalent of people on the moon,” Mr Methven added.

“It’s an incredibly exciting opportunity for the UK to be at the forefront of this new frontier.”

The aim for Step’s first phase of work is to produce a “concept design” by 2024, including an outline of the power plant, with a clear view on how we will design each of the major systems.

The Step prototype reactor, which will be built in West Nurton, Nottinghamshire, is expected to be a 100MW power station and will be used to research and develop the technology and enable a fleet of commercial plants to follow in the years after 2040.

Between 2024 and 2032, the design will be further developed through detailed engineering design and, at the same time, planning permission to build the power plant will be sought, the government said.

The aim is to have a fully evolved design and approval to build by 2032, enabling construction to begin.

By 2040, Step aims to be the world’s first commercially viable fusion plant into commission.

Politicians want Step to become an operational “mini-Sun” that contributes energy to the grid by 2040.

George Freeman, the science minister, previously said he was hopeful this could be done even sooner, in just 15 years.

Fusion makes four million times more energy than coal and creates none of the emissions or problematic waste of current energy generation methods.

It is, however, exceptionally difficult to create the conditions needed to initiate fusion and even harder to sustain it for long enough to produce more energy than it requires.

Mr Methven, speaking at an international fusion conference at the University of Oxford this week, Paul Methven, admitted that the technology is “embryonic” and refused to guarantee the project would still be live by 2040. He also declined to comment on how much more money would be needed for the project to be completed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks