The NHS workers having to battle to be with their families as they fight coronavirus on the frontline

‘I’m putting myself at risk working for the health service every day, but I’m being treated like a second class citizen,’ says Ikram, whose wife and young daughter are stranded in Kuwait due to a visa delay

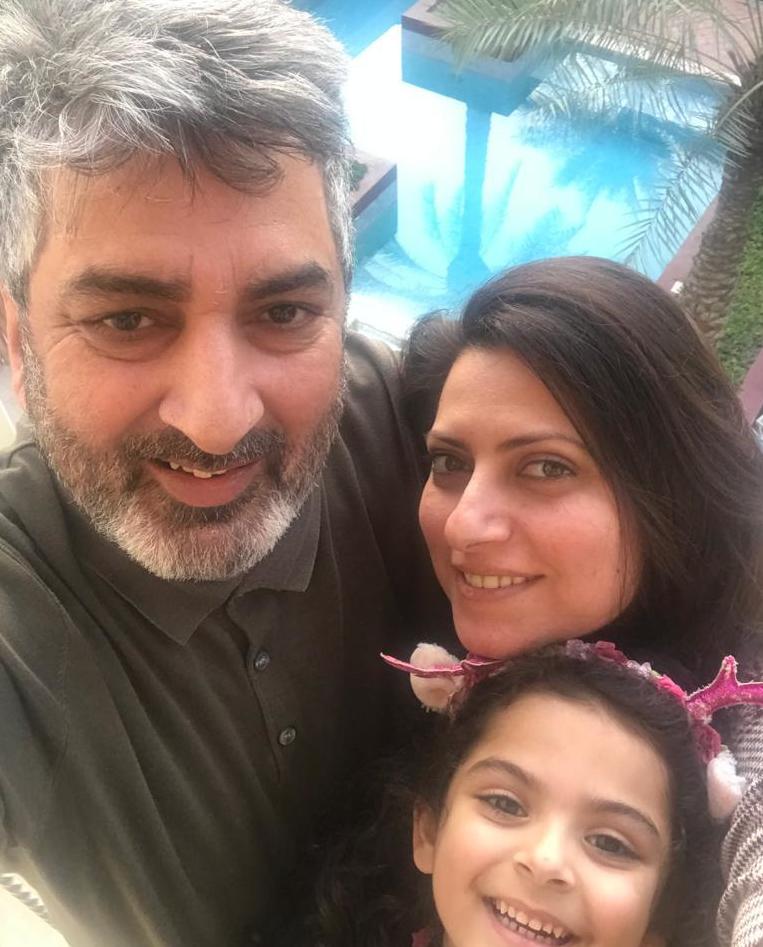

“Emotionally, I’ve been in bits,” says Ikram Khan, manager of a GP practice in Redbridge. The Pakistani national, who arrived in Britain when he was two months old, has been going into work every day during the pandemic, and had to deal with a lot of distressed patients. But this isn’t why he’s struggling. His biggest concern at the moment is being reunited with his family.

“I’m trying to stay sane for my wife and daughter. But I worry. I don’t sleep properly,” says Ikram. He hasn’t been able to see five-year old Warda – a “daddy’s girl” – in five months because she and his wife, Manal, are stuck in Kuwait due to a visa delay.

The 55-year-old’s family has encountered a number of difficulties with UK immigration over the years, including Manal’s visit visa application being rejected in 2014 – only to be granted when he wrote to the then prime minister David Cameron – and a lengthy delay in getting citizenship for Warda the following year, which wasn’t resolved until it was reported by the Manchester Evening News. But he says the delay in them being able to join him in the UK, while he toils in the NHS, has been the most devastating yet.

Ikram is one of many NHS workers who are battling with the Home Office to resolve visa issues so they can be with their families while they fight coronavirus on the frontline. More than 13 per cent of NHS staff is made up of migrants, while among doctors the proportion is 28 per cent. And while Priti Patel, the home secretary, has announced various schemes to benefit migrant workers in the health service, such as automatically extending visas for those due to expire, the delays and errors that already blighted the immigration system – and the further disarray caused to it by the pandemic – have become particularly burdensome for those working to tackle Covid-19 head-on.

Ikram met Manal while working in the Middle East in 2010 and they married two years later. Last year, they decided to move to the Britain, where most of his family is based. He was offered his job in August 2019, but Manal was unable to submit her spouse visa application from Syria, where they were living, because there is no British embassy there of visa office in the war-torn country.

He wrote to the home secretary at the time asking whether there was an alternative to Manal having to travel 800 miles to Kuwait and submit her application there, but received no meaningful response. They decided Manal and Warda would have to move there temporarily in January to submit the visa, in the hope that they would soon be able to join Ikram in the UK.

However they continue to wait for a response from the Home Office, with the department saying Covid-19 has caused delays, and later claiming that Manal’s case was “non-straightforward”.

“My daughter is British. Why can’t they do something? It’d take five minutes,” says Ikram. “I’ve been working for eight months, I’ve provided my bank statements. We’ve been married since 2012. I feel like I’m being treated like I’m not British. I’m putting myself at risk working for the health service every day, but I’m being treated like a second class citizen.”

Also struggling is Mohannad A, a 37-year-old Palestinian doctor at St Mark’s hospital in London, who has been working on the Covid-19 ward, says he feels “under-appreciated” by the government as his wife, also a qualified doctor, who asked only to be referred to as M, has been waiting two years for a decision on her statelessness application, leaving her unable to work or travel.

Having lived in Saudi Arabia for most of her life, M, who gave birth to the couple’s baby daughter in 2018, was never able to obtain permanent residence there, because Saudi law doesn’t permit those of Palestinian origin to get citizenship or permanent residence.

M came to the UK on a student visa in 2011 and joined Mohannad, who had moved to Britain in 2010, and whom she had met while they were both studying medicine in Egypt. She enrolled on a Master’s in clinical dermatology at King’s College, which she completed successfully in 2014.

When she came to the end of her student visa, M applied for recognition as a stateless person in November 2014, and eventually received a positive decision from the Home Office in February 2016. But her application to extend her stay in the UK as a stateless person in August 2018 is still pending, with the department refusing to provide any timescale as to how much longer it will take.

This has meant M has been unable to see her family in Saudi Arabia for years, including her father, who has health problems. She is unable to work as she currently has no form of ID, putting her promising career on hold and allowing her medical skills to go to waste during the pandemic.

It has also meant Mohannad, who was deployed to a Covid-19 ward earlier in the pandemic and contracted the disease himself in April, meaning he had to self-isolate for two weeks, is under intense strain as he tries to support his family, progress the immigration case and fight the virus at the same time.

“My responsibilities are growing everyday and I am struggling to keep up,” he says. “I am working almost 24/7. I help my wife with some duties in the morning and cook before leaving home, I complete my work and then rush back home to carry on family duties. This has left me physically exhausted, mentally overloaded and stressed.

“With the pandemic, the stress has been overwhelming. Covering the ward where the Covid patients are cared for has meant my work and needs in the hospital are stretched. I feel under-appreciated and unsupported as I have been working hard while our matter is not looked at or cared about by the government, despite the fact that we we delivering out duties for this country and its people.”

M says she feels “disappointed” with the UK government for the way the family is being treated: “I’m a doctor with a Master’s degree in dermatology and I could help this country during coronavirus wave. I haven’t been able to visit my family for years because I don’t have an ID.

“My father was admitted to hospital and I couldn’t travel to see him or let my baby see her granny and relatives. My husband has been working on the frontline fighting coronavirus. It seems the Home Office has no rules to finish these applications, leaving them to take years.”

A government spokesperson said they did not comment on individual cases and pointed to the additional measures put in place, adding: “We are incredibly grateful for all the hard work that health workers and care workers continue to do in the fight against coronavirus.”

Mohamed Fadil, 28, an IT risk manager for NHS Greater Manchester, has been working to ensure GPs and clinicians across the city are able to provide services from home. But he says he feels he has been “rejected” by the government after his spouse visa extension was refused last month due an apparent error in it processing – and he has no power to appeal it.

“I was in the middle of doing all this work for coronavirus then I received the rejection. It wasn’t very nice. It’s like – thanks for your service, but no thanks,” says the Libyan national, who’s been in the UK for seven years with his British wife, a pharmacist, and one-year-old daughter.

While Mohamed’s initial spouse visa application at the end of 2017 was accepted with no issues, his attempt to extend the visa, which all migrant spouses are required to do after two and a half years, was refused because he didn’t meet the £18,600 income threshold – when in fact he earns a sum considerably higher.

Despite this, his attempts to reverse the decision have been met with the Home Office saying he cannot appeal. He said: “I feel disappointed. I’m trying to make myself useful to this country. The fact that I have to pay the NHS health surcharge is on its own difficult to comprehend, and then on top of that I get this refusal and they’re not willing to acknowledge their mistake, and then they say submit a fresh application at a cost of over £2,000, is extremely upsetting.

“It feels like a one-way relationship with this country.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments