Inside the South Korean ‘doomsday cult’ recruiting young Black Christians in the UK

Investigation: ‘You feel special, you get lost in it, you feel chosen and you start to believe in what they’re saying,’ ex-member says

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Joshua Adeyemi’s bible study leaders eventually told him the name of the church he was attending, he says the information came with a request – do not research it.

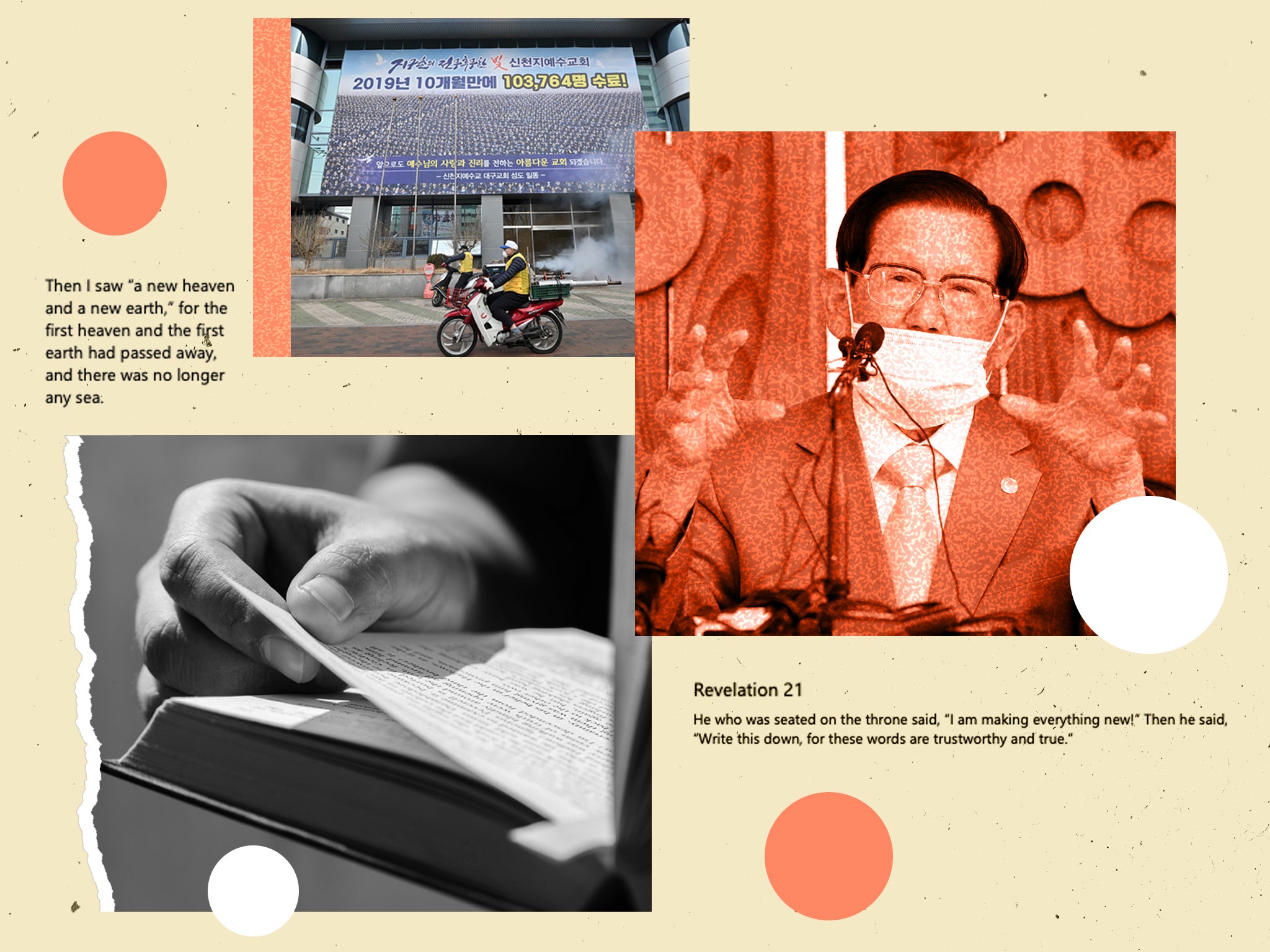

Joshua had been attending online study sessions for two months, 7pm-9pm, three days a week. But it would be another four months before he realised he was part of a “doomsday cult” called New Heaven New Earth (NHNE), or Shincheonji. Members believe that a South Korean man, Lee Man-hee, is a “chosen messenger of Jesus” on Earth to bring about the Second Coming. Had Joshua done that research, he might have learned sooner of Lee Man-Hee’s conviction for embezzling the church’s funds.

“The first two months they keep it very vague so you think it’s just a bible study with other Christians. But as you learn more you feel special, you get lost in it, you feel chosen and you start to believe in what they’re saying,” he said.

The 20-year-old is one of a number of ex-members who have told The Independent their concerns about the group’s recruitment techniques – said to “target” young Black people – and its practices, which many say leave them isolated after they are encouraged to abandon their family and friends.

Representatives of Shincheonji said that the group was now more open and its members were able to pursue careers and interests outside the sect.

The group has bases in London and Manchester but its reach is much wider, with hundreds of people attending Zoom meetings. Many more potential followers have been approached by members on social media after the pandemic forced the group’s activities online.

Joshua was approached on Instagram by a NHNE member in September 2020 and was soon having Facetime calls with them about his Christian faith. He went to an introductory Zoom session in December, which he thought was full of new recruits. He claims he later found out that a number of the people on the call were in fact members pretending to be going along for the first time.

From there he was signed up for one-to-one mentoring sessions, a bible study course, and he became a member in February 2021. He left some six months later in July after he grew concerned about what he was reading about the group online.

Have you been impacted by anything in this story? Email holly.bancroft@independent.co.uk and thomas.kingsley@independent.co.uk

“The first weird thing they did was tell me not to tell my parents. My parents are Christian so I thought I would be able to tell them but the way they described it, they said it was too deep, and I should keep it between just us,” the Nottingham Trent University student explained.

Soon he felt the group had taken over his life. “I was cutting off my friends and family. No one in my life actually knew I was going to the sessions.”

He said there were many times when members would put pressure on him to make a choice between them and his friends, or ditch his university work so he could study their teachings.

As he was learning more about the doctrine, he grew convinced that he was witnessing the Second Coming and the imminent end of the world. “It’s like a doomsday cult,” he said. “They make it seem like it’s happening right now.”

A ‘promised pastor’

On top of Shincheonji’s study course, members are required to take tests, which evaluate their knowledge of the group’s doctrines and assess their worthiness for salvation.

Those who study to a sufficient standard will allegedly be part of a chosen 144,000 people from the tribes of Israel mentioned in the biblical Book of Revelation.

Shincheonji (SCJ) has far exceeded 144,000 members internationally, and so the UK group is said to be recruiting the “heavenly multitude” clothed in white mentioned in the apocalyptic book.

One ex-member estimated there were as many as 450 members in the UK branch.

The church, which is considered a cult by many, was founded in 1984 in South Korea by 90-year-old Lee Man-hee.

Details about Lee Man-hee’s role within the group are apparently only revealed many months into the initial bible course and when they were recruiting, ex-members said they were told not to mention Shincheonji.

Jonah, a design manager, who was in month two of the group’s course when he spoke to The Independent, was recruited through LinkedIn by a young woman asking if he could help out with a project on men’s mental health.

After a few introductory phone calls, she invited him to an online event with NHNE.

This is apparently a common tactic for recruitment to NHNE, with one former UK member telling The Independent that they were given training tools that would “deceive” people into attending online sessions. These tools allegedly included advice to pose as a psychology student doing a research project or to approach people with fake surveys.

Jonah’s initial Zoom meeting was attended by about 100 people and he was soon going to bible sessions on Monday, Thursday and Sunday each week, with around 70 others.

“I was told not to use the internet to research things. They tried to head off the online accusations that they are brainwashing people and being forceful,” Jonah explained.

“One of the concerns I’ve had and still have is about why most of the congregation are young Black people, why aren’t there any white males?” he said.

The group’s majority Black congregation has also been noticed by others, who told The Independent of their fears that young Black Christians were being “targeted”.

According to two ex-members, the significant proportion of Black people within the UK branch of the sect has been a concern to leaders of the international group, who sent a diktat in 2015 that more white people should be recruited.

Social media recruitment

The Independent has seen evidence that suggests members of the UK-based branch have been approaching young Black people, in their twenties and thirties, on social media platforms.

One of those was 24-year-old Cambridge student Nia. A budding artist, she wasn’t put off when she received an inquiring message in her Instagram inbox.

It read: “Just came across your profile and I just love it! Can I ask what inspires you?”

It was a question that would lead to what she describes as a close escape. “I felt like I was crossing the road and a massive van was coming towards me. You take a step back and it goes rushing past you, and you think you could have died,” she said.

The message asked if she wanted to help with a blog about “what drives people and their passions”.

“I’m tasked to speak with 100 people by the end of April… Will you be the 78th person?” Grace, a project manager at a global media business, asked.

Nia had two calls with Grace and ended up agreeing to read the bible with her. That’s when “things started to get weird”, Nia said.

In their second study, she was told that the Old Testament father Abraham practised wisdom when he hid his plan to kill his son Isaac from his wife.

The story, known as Abraham’s test, is a well-known part of the bible where God asks Abraham if he will sacrifice his son, Isaac, only to step in at the last minute to stop him.

Nia explained: “She said that the reason Abraham is a faith hero is because he did this secretly. She said that he got up early in the morning to avoid his wife and do it. Then she started saying this means it’s OK to lie to people around you if you are doing it for God’s purposes.”

Funmi Adeyo, a data and artificial intelligence consultant, was told something similar.

“I went about three times to the follow-up bible studies but by the second time I realised something fishy was going on,” she said. “She was telling me not to tell people that I was going. I remember having a back and forth with her about it because she was telling me to lie.”

‘Racial targeting’

Both Nia and Funmi felt they had been targeted because of their race and faith. “They target people who want to know God more. I think they’re targeting Black people as well, a number of my friends who are mainly Black have been approached via Instagram and LinkedIn,” Funmi said.

“I felt like it was very orchestrated,” Nia said. “If she had been a Black man messaging me on Instagram I never would have replied, but she felt like a mentor age – around 30 – so six years older than me.”

“I think they target people who are either in a transition stage or in a vulnerable place.”

Deborah Adefioye, a marketing consultant in Manchester, has been approached on LinkedIn and Instagram by the group at least six times this year.

She said: “I think they’re purposely using Black women so it feels like we have stuff in common. Maybe I’m more likely to put my guard down because it’s someone that looks like me.”

Shelley Fleuridor, a leader at a youth church in Manchester, said members of her church had been repeatedly approached by the group, a lot from last September onwards. “Everyone was saying ‘I just got this message on Instagram’,” she said.

Another recruit, 28-year-old Brianna, moved to London from Zambia during the pandemic and joined an app called Platook to make friends.

She chatted to mostly Black women in their twenties and thirties from London for a year during the 2021 lockdown but eventually, the friendships faded out.

Then on 8 January 2022, one of the friends messaged her on Whatsapp with an invite. “Happy new year!” she said, “I’m trying to keep spreading some holiday cheer in January through some free online Christian events I will be attending during this week organised by NHNE.”

She sent over an Eventbrite link to a Zoom event called Reset 2022, which promised to help attendees find out about God’s plan for their lives in the new year.

Brianna said she wasn’t interested, but on 11 January she received an invite to the same event from another of her friends. Then three more separate invites followed days later, including one on LinkedIn from someone she didn’t know.

“I felt so let down,” Brianna told The Independent. “I feel like I invested a year of my life getting to know these people and I feel like they just had a mission.”

“Particularly the LinkedIn message really freaked me out. It was like they were sharing my information.”

A month prior to The Independent’s investigation, one of our reporters – also a young Black Christian – was approached by a member of NHNE on LinkedIn.

He was asked whether he wanted to learn how to “hear the voice of God” with no indication that the event was hosted by a group connected to SCJ or Lee Man-hee.

He attended the Zoom meeting as part of our investigation. Some 106 young attendees – mainly young Black people – were present at the two-hour meeting, with participants strongly encouraged to have their cameras on throughout the call.

‘Hand-picking recruits’

Ex-members of the group told The Independent that recruits were assessed according to criteria and it was common practice to write reports on new members.

In an “evangelism diary” seen by The Independent, members fill out a form on new joiners, including answering questions such as “Does he/she have depression? Is he/she homosexual? Is he/she a shift worker?” and even “You know how suspicious and aware he/she is of cults”.

Jess Xentsa, who was part of the Manchester branch for 11 months in 2020, said it all started with the “worthiness criteria”. “You can’t have any physical or mental health issues, because people in there need to be able to be faithful and work, and work means recruiting,” she said.

She explained that she had to make sure that recruits had a visa to stay in the UK. “We didn’t have asylum seekers in the group, or someone here for a holiday,” Jess said. “They have to also be a Christian because it was too difficult to teach the content to unbelievers.”

Jess claimed that the teachers in her Manchester-based group had all been living in one flat.

“They don’t work, they no longer have their individual lives,” she said. “They’ve committed everything to Shincheonji as a cause.”

She said that the full identity of the group, and their belief in the “promised pastor” Lee Man-hee, was only revealed some three months into her study course.

She said she had to pass regular “seal tests” on what she was learning, and only then was she allowed to go for “Passover” in the temple – in her case “a building in a business park”.

On graduation from the bible course, she headed to a business park in Canary Wharf for her confirmation ceremony and signed the “Book of Life”.

“When you fill in the Book of Life there is also this huge form,” she explained. “You have to fill in your name, your blood type, what car you have, the number plate, how long you’ve been driving for, everything that people can know about you.

“When your siblings were born, your parents’ date of birth. I remember walking in one time and people were pricking their fingers to do a blood test. Why they wanted our blood was one thing I never got a definitive answer for, but if you look at the culture of East Asia they believe a lot about the purity of blood types and links to personality.”

Isolation from family and friends

The most worrying thing for Jess was the way the group appeared to extract people from their family and friends.

“A couple of young people, who had families who were getting anxious about their involvement, were told to leave their families.

“A lot of families and friendships were broken up,” she said.

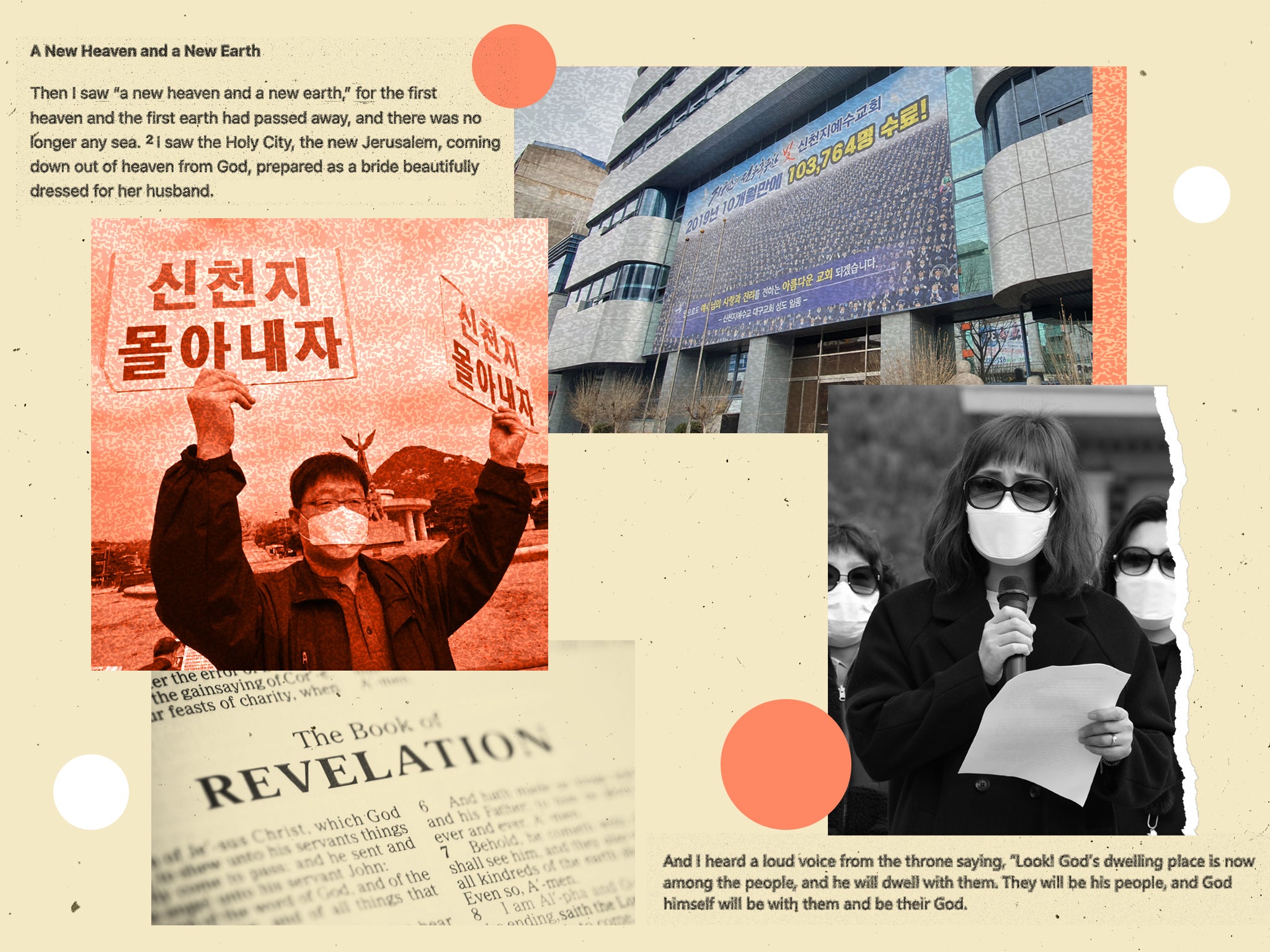

Responding to claims about the way it operates and its recruitment techniques, lawyers representing Shincheonji said “covert” evangelism “was part of a phase of the history of Shincheonji that is now being abandoned”.

They said that Shincheonji was now more open and added that in the past, when members “tended not to reveal” their involvement with the group to their friends and family, this was because of the “hostile campaigns” against Shincheonji, which had caused members to be “ridiculed and bullied”.

Referring to claims that SCJ took over people’s lives with intense time commitments, representatives for the group said that “not all Shincheonji members are full-time missionaries, just as not all Catholic women are nun [sic]”, adding that members were able to pursue full-time careers and obtain college degrees.

“In case of those who decide to devote their lives to the church, it is possible that their parents or relatives are unhappy with their choice,” they said.

“It is certainly true that Shincheonji does recommend to members not to read anti-Shincheonji literature, including articles found on the internet,” they added.

Referencing the records it keeps on members, the lawyers said they were examined by South Korean courts last year and found to be unobjectionable. Finally, they objected to being described as a cult and said this report was based on the accounts of ex-members and said the term “cult” was a “derogatory, stereotyping label” which had been abandoned by scholars of “new religious movements”.

Laurie, a former head instructor of the church’s Namibian branch, now helps Shincheonji members who are seeking advice on leaving the group.

“Some people grow up in SCJ. They come in when they are 18 to 19 years old and so when they leave some years later they don’t know how to live a normal life, where you can make your own decisions and be free,” he explained.

“We’ve had a lot of cases of people, when they leave SCJ, starting to do a lot of drugs, drinking a lot, sleeping around all in excess because they don’t know what to do.”

“You develop a fear of trusting people and you have issues with friends and family who think you are stupid for joining this cult.”

“That’s why a lot of us, when we left SCJ, we reached out to other ex-members. A lot of people try to speak to psychologists and even they don’t understand because they don’t specialise in religious trauma.”

Rod and Linda Dubrow-Marshall, University of Salford academics who have researched the coercive persuasion techniques of cults, said that everyone is potentially vulnerable to these groups, especially when they are going through a difficult or transitional time.

“Cults also target people who already believe in some of their ideas, so a group such as Shincheonji will focus on Christians and con them into attending classes and events. They will use a bait and switch tactic to then indoctrinate them into the more extreme and controlling ideology and practices.”

Michael Thomas, head of the charity Reachout Trust which helps cult members, said: “When you are growing up, the relationships you have with people are what gives you the confidence to be who you are.”

“They break up those relationships and seek to take the place of them. If you decide that you don’t want to be a part of the group anymore, those relationships aren’t there. You’ve been cast adrift.”

Some names have been changed to protect identities

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments