How a dozen silk stockings helped bring down Adolf Hitler

And how newly declassified documents show the greatest double-cross operation of the Second World War was nearly ruined by a Spanish double agent's wife's horror at British food - and her willingness to die rather than 'live another day in England'

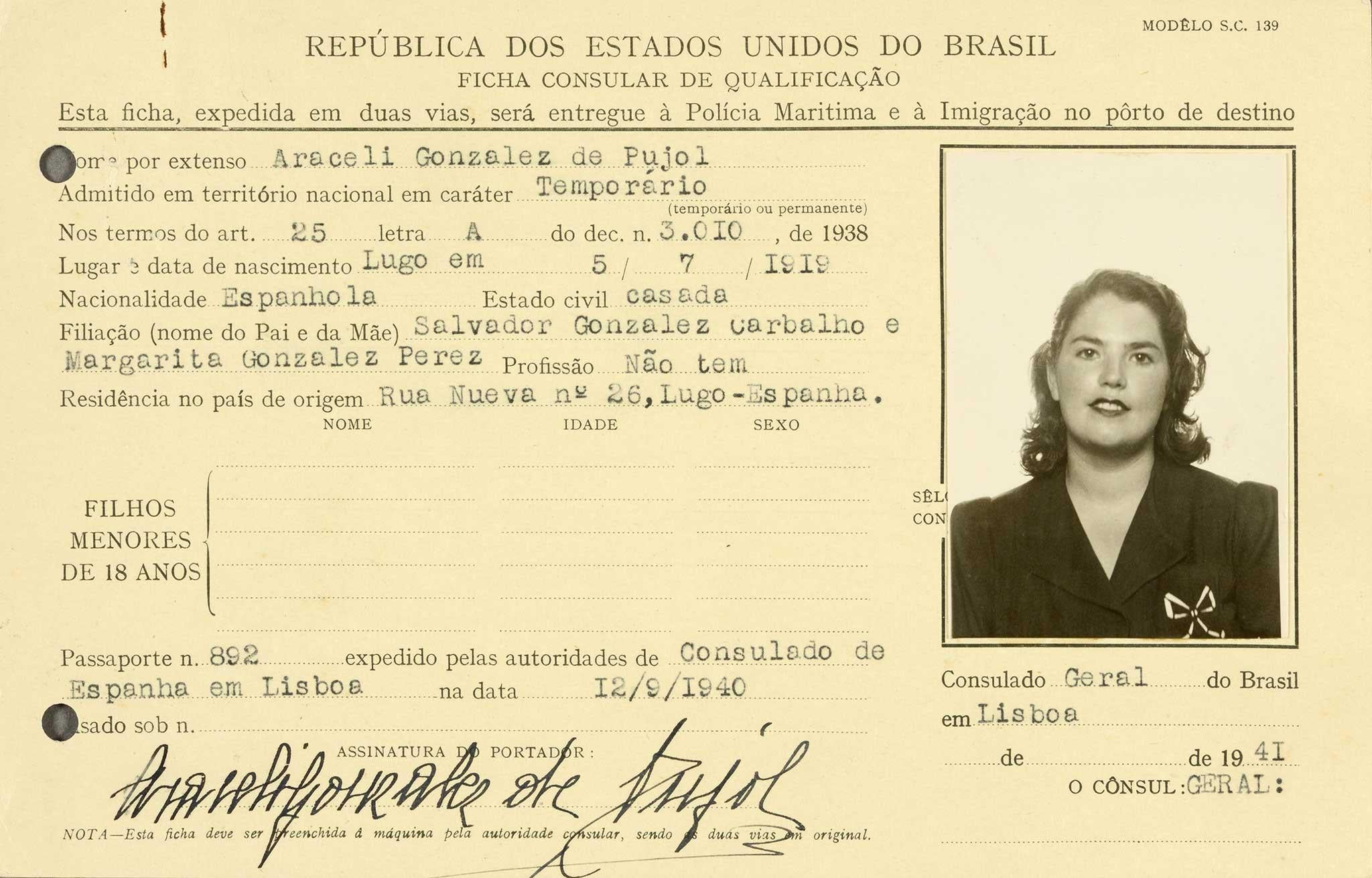

!['Mrs Garbo', Araceli Gonzalez de Pujol, complained of 'too much macaroni, too many potatoes [and] not enough fish'.](https://static.the-independent.com/s3fs-public/thumbnails/image/2016/09/22/10/mrs-garbo.jpg)

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Possibly the greatest double cross operation in British espionage history was nearly ruined by a Spanish double agent’s homesick wife and her horror at wartime British food, newly declassified documents have revealed.

Juan Pujol Garcia, codename Agent Garbo, has been described on MI5’s own website as “the greatest double agent of the Second World War”, and by Spanish film makers as “the spy who saved the world”.

On his own initiative, the industrialist’s son from Barcelona approached the Germans and tricked them into thinking he wanted to spy for them.

He went to England, working with MI5 to create a whole network of entirely imaginary agents and feeding misinformation to the Nazis, culminating in the ultimate triumph: a leading role in securing the success of the D-Day landings by convincing the Germans the main invasion would happen around Calais, not in Normandy.

Throughout it all, “the small meek young Spaniard”, as his MI5 handler called him, was never the problem. He fooled the Germans so completely they awarded him the Iron Cross.

The problem was the meek young Spaniard’s wife.

As newly released documents at the National Archives reveal, “Mrs Garbo”, Araceli Gonzalez de Pujol, had never left the Iberian Peninsula before she arrived in London in the spring of 1942.

Speaking no English, missing her mother, the 23-year-old became terribly homesick. Mrs Garbo was, the documents reveal, horrified by having to swap a Mediterranean diet for the rationed offerings of a country that was still decades away from accepting haute cuisine or the gastropub.

Her despair at “too much macaroni, too many potatoes [and] not enough fish,” was duly noted by MI5.

So too was the fear that driven by the desire to go home to mother, or to the Spanish Embassy in London, Mrs Garbo might divulge to a fascist power the secrets of what was fast becoming the most successful double cross of the Second World War, and arguably of British espionage history.

So it was that on 22 February1943, agent C P Harvey of MI5 was ordered to neutral Lisbon, Portugal, with a top secret mission: to purchase 12 pairs of silk stockings for Mrs Garbo.

Harvey was left in no doubt as to the importance of the stockings, at a time when silk was in short supply in Britain, with most of it going to make parachutes not hosiery. Mrs Garbo had been promised the stockings, he was told. An MI6 agent had already been to Lisbon but failed to secure the stockings, on account of failing to ascertain the size required.

“It would,” Tommy Harris, Agent Garbo’s MI5 handler, warned Harvey, “make a very bad effect on her morale” were Britain not to honour its stockings promise. This was now “a small matter of some importance”.

Fortunately, Harris had established that Mrs Garbo took the same size stocking as Mrs Gill, wife of MI6 officer Gene Risso-Gill.

“If you cannot get the size from Mrs Gill,” Harvey was ordered, “please get any small size”.

On 4 March, Harvey returned from Lisbon with the message: “Herewith 12 pairs of stockings for Mrs Garbo for which I expect to be repaid 10/- [10 shillings] customs duty.”

News that the stockings mission had been accomplished was relayed from MI5 to the Secret Intelligence Service MI6, in a document now filed for posterity in the National Archives as “To SIS re Mrs Garbo’s stockings.”

Harris confirmed to Major Frank Foley, who would later be celebrated as a “British Schindler” for his work helping Jews escape pre-war Berlin: “Mrs Garbo is, as you can imagine, delighted.”

Nor were MI5’s efforts to help Mrs Garbo, who was left in a house in Harrow, north London, with two young children while her husband worked long hours winning the war, confined to stockings.

As the hitherto secret documents reveal for the first time, Britain’s security services were ready to do almost anything to assuage her homesickness.

The documents, however, suggest a constant struggle by a service staffed mainly by stiff-upper-lip Englishmen, many perhaps accustomed to equally stiff-upper-lip English wives, to accommodate a less reserved Spanish woman.

“Her desire to return to her home country, and in particular to see her mother, has driven her to behave at times as if she were unbalanced,” wrote Harris, who at least had the advantage of having a Spanish mother and having been educated in Spain and at the British Academy in Rome. Harris, however, decided it was his duty to press on.

“I feel,” he wrote, “That one cannot hope in a case as complicated as this, dealing with such temperamental people, to free oneself from the entanglements that are bound to arise.”

With so much of the war effort at stake, concessions could even be made over British food.

“The entire domestic situation made a complete change for the better,” wrote Harris in March 1943, “Immediately Garbo was given his own way and was permitted to keep house for himself.”

Harris also considered Agent Garbo’s suggestion of smuggling two new assets to England – Mrs Garbo’s mother and “serious” older sister.

“He [Agent Garbo] says that her mother would look after the children as well as keeping Mrs Garbo in order,” wrote Harris. “The sister, who is a serious woman, 17 years older than his wife, would look after the house.

“Mrs Garbo would have company and be able to chatter in Spanish all day long.”

But despite efforts more worthy of Ealing Comedy than Great British spy thriller, it all nearly ended in disaster. On the night of 21 June 1943 His Majesty’s secret service was alerted to a volcanic row between the Garbos – by an enraged Mrs Garbo.

As revealed by the document “Report of a hysterical evening with Mrs Garbo”, she phoned Harris to tell him she couldn’t stand living in England. She was going to the Spanish Embassy, she said – threatening a move that would have blown the whole operation because the Spanish would inevitably have shared the intelligence with their fellow fascists in Germany.

“They may kill me tomorrow,” said the desperate Mrs Garbo, “But I don’t want to live another day in England.”

“I don’t want to live one day more with my husband,” she told Harris. “You can stay with him.”

In this crisis, Garbo showed devotion to duty that won the everlasting admiration of his handlers, proposing “a drastic plan ... which, had it failed, would have ruined forever his matrimonial life.”

He suggested everyone pretend to Mrs Garbo that his superiors had told him he was being removed from operations and he had responded with such violent fury he had been arrested.

After “weeping incessantly for many hours on end”, Mrs Garbo was taken to Camp 020, the south west London interrogation centre for captured Nazi agents, to see her husband unshaven and dressed in prison uniform.

After “copious tears,” Mr Garbo signed an apology and asked “a thousand pardons”.

Agent Garbo was able to go on to help deceive the Germans so thoroughly that for two months after the June 1944 D-Day landings, they kept two armoured divisions and 19 infantry divisions waiting in the Pas de Calais for an invasion that would never come.

Had the Germans realised they were being played, the official history of British Intelligence in World War II records, the intervention of some of these divisions in the Normandy battle “really might have tipped the balance” in the Nazis’ favour.

Instead, on 29 July 1944, to Garbo’s great amusement, he was informed he had been awarded the Iron Cross by Hitler himself for his “extraordinary services”.

It is said that when informed of Agent Garbo’s “great ingenuity” and the “facile and lurid style” in which he lied to the Germans, Churchill declared: “In wartime, truth is so precious that she should always be attended by a bodyguard of lies.”

The Garbo operation is all the more incredible given that, as the newly released files confirm, the disdain of British officialdom nearly killed it before it began.

Summarising the early stages, Harris writes that while working alone in Lisbon, pretending to the Germans he was in Britain – and making schoolboy errors, like claiming Glaswegian dockworkers would do anything for “a litre of wine” – Garbo and his wife repeatedly suffered “the cold rebuffs of officialdom”.

In late 1941, in Lisbon, Mrs Garbo met a “very rude … tall, young Englishman” who claimed to be from British Intelligence. With sarcasm that subsequent events proved wholly misplaced, he dismissed her with the comment: “Do you think you are going to win the war for us?”

Fortunately, Agent Garbo persisted. He helped save Europe from fascism – but he couldn’t save his marriage.

After the war, after faking his death to avoid reprisals from surviving Nazis, an agent who had, in Harris’s estimation, been motivated by hatred of fascism and love of adventure, divorced “Mrs Garbo”. After remarrying, he died in Caracas, Venezuela, in 1988, aged 76.

“He was the best double agent Britain had during the war,” said Professor Christopher Andrew, author of the official history of MI5. “But the case was in danger of being wrecked by family problems. Her threat [to go to the Spanish Embassy] would have risked the most terrible consequences. The success of D-Day may seem inevitable now, but it was the biggest gamble in the history of amphibious warfare.

“It is far easier to run double agents if they are single.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments