Hunting ‘The Scorpion’: My mission to track down the gangs smuggling migrants across the Channel

This week Yvette Cooper pledged to go after the criminals behind the thousands of migrants who cross the Channel every year. She won’t find it easy and will be shocked by what she discovers, says Sue Mitchell, whose leads took her to corner shops in Nottingham and affluent suburbs in Belgium in her year tracking down some of Interpol’s most-wanted

As 2024 began my colleague Rob Lawrie and I set out on a secret mission. I’m an investigative journalist, Rob’s an ex-soldier, now an aid worker, and we have combined our talents in the past, working on immigration stories. Together, we had tracked and traced families, some with tiny children, across Europe and spent time in the French camps as they prepared to reach Britain.

There have been more than 50 deaths so far this year, but it has done nothing to stem the numbers attempting this perilous journey: the running total for 2024 is up 16 per cent to almost 32,000 compared with the same point last year.

At the Interpol General Assembly in Glasgow this week, Keir Starmer announced more money for this issue and revealed new agreements with countries in the western Balkans, particularly focusing on sharing intelligence.

The home secretary, Yvette Cooper, says it will take time to get investigators and new technology in place, but has pledged to “go after the criminal gangs at the heart of this”.

The challenge the government faces is enormous, as we discovered this year when we set out to track down and expose the smugglers themselves. The people who organise the operations, commission the boats and promise entry to the UK via rubber dinghy.

We had one target in mind: a man on the Interpol most wanted list who is known to have brought thousands of people across Europe into Britain.

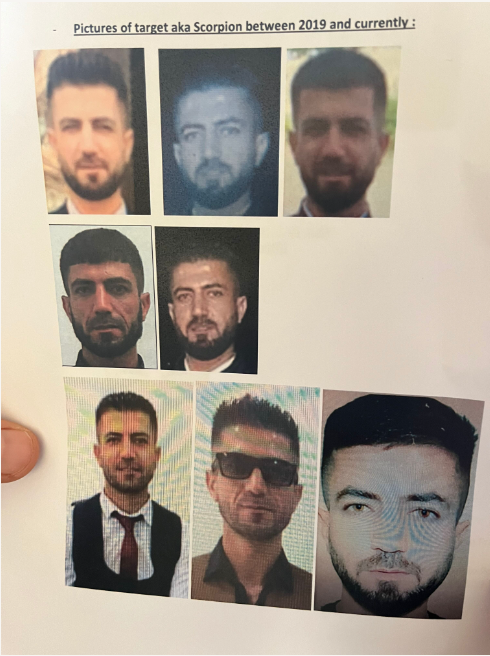

His name is Barzan Majeed, but he is known as “The Scorpion”. Majeed is 38 and an Iraqi Kurd. He’s also tough and fleet of foot. When an international police surveillance operation caught 25 members of his gang, he was tipped off and disappeared. When we started to look for him, there were few clues.

Rob and I got going by asking questions of our contacts in the camps. People were scared and either told us they knew nothing, or warned us off. One man told us that the smugglers are armed and would do whatever was necessary to protect their trade: “I’m not scared of anyone, but these guys, yeah, they will put a bullet in your back.”

People smuggling using small, inflatable boats began in earnest in 2019 when the surveillance of lorries arriving in the UK was tightened. Back then, Rob and I met a little girl called Marianne who almost died when one of those first dinghies sank in the English Channel.

There were 19 people on board the rubber boat and not one lifejacket. Benzine from the outboard engine had mixed with the seawater and become corrosive. Marianne and her mother showed us the livid scars from the burns they suffered. And young though she was, Marianne knew she almost didn’t make it: “I was scared, this was so scary. I was so cold it made me want to die.”

The terrified child and dangerous dinghy were the first links in a chain that would eventually lead us through the ranks of a criminal gang to the man at the very top – The Scorpion.

When police in the UK pick up migrants, they take and inspect their mobile phones. The Scorpion’s number was found in thousands of them – he uses a picture of a scorpion when he sends out messages on WhatsApp.

Martin Clarke, a senior investigating officer at the National Crime Agency, told us how significant that image was: “Some of these crime gangs like to use an alias to gather kudos. We were seeing an avatar of a scorpion over and over and the more we looked, the more Majeed started to feature. You begin to realise that he's a very significant individual.”

The officers at the NCA helped us by sharing some of what they knew about Majeed. They showed us his immigration record and we were astonished to learn that he had lived in the UK for almost a decade. He was smuggled in, in the back of a lorry, in 2006 aged 26.

He used a false name and claimed to be an asylum seeker fleeing persecution in Iran. His records say he was refused leave to remain after a year, but no one made him leave, even though he was in and out of prison for handling firearms and taking and dealing drugs. British authorities only discovered his true nationality when he slipped up, using a prison phone to make a call to his mother – the number he had dialled was in Iraq.

On the brink of being deported, The Scorpion agreed to voluntarily leave the UK and return to Iraq. This was in 2015 – just as millions of people, displaced by wars, were trying to make their way to Europe from Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, Somalia and Eritrea.

People smuggling was a huge international business and The Scorpion was in luck – his brother, Carzan, had been sent to prison in Belgium for people smuggling and passed over his business to his brother. Under Carzan, the trade had all been about lorry crossings but by 2019, The Scorpion saw the potential for small boats and for expanding his gang across Europe.

We started our search for The Scorpion in Nottingham where he used to live. By using photos on an old Facebook page to trace the car wash where he worked when he first got to the UK in 2006 and which he later ended up buying.

One migrant told us how he had been smuggled into Britain and was told to report to a small convenience store and given work, cash in hand, in a car wash. He helped us find the store and I went in, while Rob kept watch as I questioned the manager about claims that the business was picking up migrants from the beaches at Dover and putting them to work. He started messaging on his phone and within minutes four cars with blacked-out windows had pulled up outside. They started taking photos of us and we made a very hasty exit.

We knew from other programmes we’ve made exposing people smuggling that when you question people profiting from it, word goes out. Criminals will get in touch out of curiosity, or to put their side of the story. Enemies also have an interest in bringing other smugglers down: you can get good information from rival gangs, settling old scores. The families of migrants who drown at sea also may be looking for justice and so share what they know.

We saw how decent people trying to help migrants inadvertently help the smugglers, funnelling clients to them. After Nottingham, our trail took us to a respectable, middle-aged woman in an affluent Flemish village in Belgium who had turned her big house into a migrant hostel. It even has a secret room for people to hide from the authorities. We found evidence connecting some of the people staying with her to The Scorpion and a nearby lorry park he controls – the chain-link fencing has been removed to allow access to lorries bound for England.

We heard from a wealthy Iranian who dealt personally with The Scorpion: he and his relatives were offered a new “first-class” smuggling service – a premier cross-Channel ferry route costing them £18,000 each.

They boarded the ferry in Calais, right under the noses of the authorities. We were so astonished that the man offered to draw us a map of the exit gate they were told to report to. This gate is only ever to be used by staff at the port. The Scorpion had told them they should come smartly dressed and stride with confidence. They’d then be picked up by a corrupt official who’d drive them onto the ferry, avoiding British passport controls. The man even brought them a full English breakfast on the ferry to celebrate their new life in Britain.

Our breakthrough came by linking The Scorpion with migrant crossings from Turkey across the Mediterranean to mainland Europe. Rob’s contact had sent us to a cafe in Istanbul used by the people smugglers. When we asked the manager if he could tell us about the trade – the room went quiet and a man passing our table opened his jacket to show us he was carrying a gun. Rob and I made yet another swift exit, but not before someone slipped us an Istanbul address for our man, Barzan Majeed.

We were too late to find him there, but some men in a cafe opposite knew who he was. We left them our number and later that night, Rob’s phone rang. He raced along the corridor in the hotel to bang on the door of my room – Majeed had telephoned us. He wanted to know what we were up to and why we were asking so many questions about him.

We eventually tracked down a villa in Marmaris he was using. By asking around we were able to build up a picture of his life there: the smuggling boss high on cocaine sending yachts from Turkey to Italy. These yachts are stripped out so they can hold 100-plus migrants, bringing in thousands for each crossing. A girlfriend told us about the fast cars, the nights out and The Scorpion’s love of money: “He wanted to be a trillionaire. I warned him to stop, but he wanted more.”

Then we got word that The Scorpion had been spotted in a money shop in Iraq. Following a violent man to a violent country made us nervous and we knew The Scorpion would be armed and that things could go badly if he felt cornered. But we couldn’t give up. One of Rob’s contacts offered to mediate and reassure The Scorpion that we hadn’t been sent to take him back to face the 10-year jail sentence he had escaped. Telling him we were journalists just looking for information and he agreed to meet in a coffee shop.

Within minutes of sitting down we saw Majeed walking towards us, shadowed by his security team who sat on the table behind. He looked like an affluent golfer, with a light blue shirt and black gilet. He looked at ease.

We probed him about the loss of life, about the children rescued at sea, but his detachment was chilling. The people going on these boat crossings, he said, only had themselves to blame if things went wrong: “God doesn't never say go inside the boats; they do that themselves”, he said. “They’re begging the smugglers, please, please, do this for us. And then they complain. They say this, that. No, this is not true.”

His stare was cold, he had no remorse and he made no effort to cover up his crimes saying he’d smuggled, “maybe a thousand, maybe ten thousand. I don’t know, I didn’t count.”

While insisting his people smuggling days were over, as he spoke, he was scrolling through his phone. He didn’t realise it, but we could see his screen reflected in a polished picture frame on the wall behind. He was checking lists of passport numbers that are sent to corrupt officials to get visas for migrants. It helped explain his luxury lifestyle, the gated compound, top of the range cars and designer clothes.

As news of our investigation broke, we were contacted by the deputy prime minister of the Kurdish government in Iraq, Qubad Talabani. He said he was disgusted to hear that a man as dangerous as Majeed was living a life of luxury in Iraq, making money from such misery.

The speed of what happened next took us by surprise: that weekend an elite police group was positioned outside the address we had tracked The Scorpion to. A short time later he was behind bars, awaiting trial in Iraq.

It would be comforting to think that Majeed was the only man at the top of an international people smuggling ring, and that his capture would warn others off, but it’s far from the case.

The National Crime Agency is currently overseeing 70 live investigations and this week joined forces with French authorities to secure the conviction of 18 people for people smuggling. The head of the NCA, Graeme Biggar, praised our investigation and the result achieved.

In the wake of The Scorpion’s arrest, European crime agencies have provided details of other smugglers thought to be hiding out in Iraq and there have been subsequent arrests, showing what can be achieved by this kind of international cooperation. It isn’t easy but it can effectively target the smugglers and make them pay for the desperate tragedies we’re witnessing in the English Channel.

‘Intrigue: To Catch a Scorpion’ is available to listen on BBC Sounds