Metal detectorist unearths 1,150-year-old Viking board game

Hnefatafl pieces may be oldest collection ever found at one site

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A metal detectorist has unearthed a viking board game in Lincolnshire dating back to 872 AD.

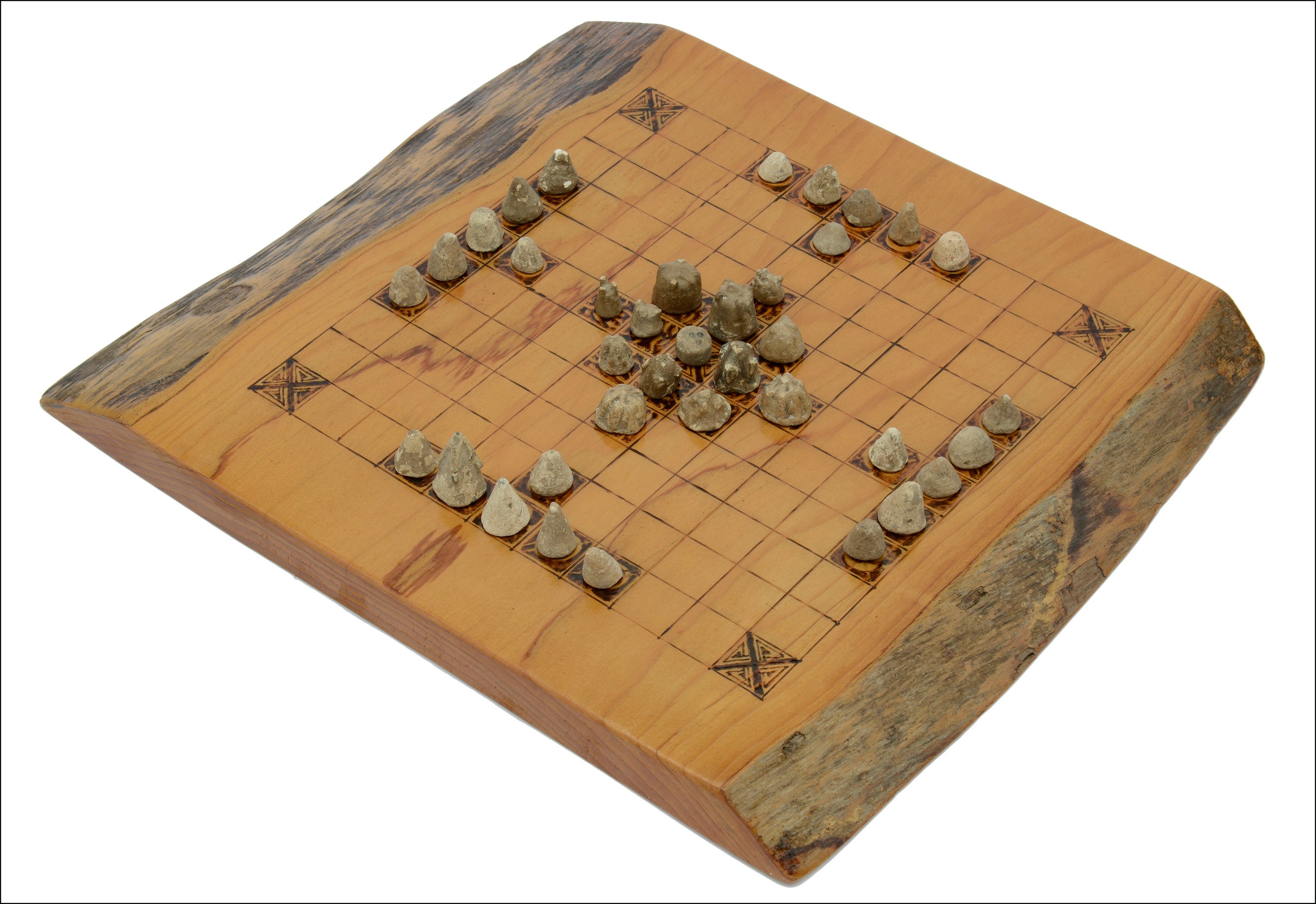

Mick Bott, a retired miner, made the rare discovery of a complete set of 37 pieces used in Hnefatafl — a chess-like game popular with soldiers for its strategic nature — at a site next to the River Trent.

The 73-year-old had spent 20 years searching for items at the location where, thanks to his efforts, historians now know Vikings set up camp throughout the winter of 872 AD.

From his first detecting session at the Torksey site in 1982, Mr Bott and two fellow detectorists unearthed hundreds of coins, strap ends, brooches, and mounts, all of which were from the ninth century.

“It was later on after showing many of our finds to the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge that the experts realised that this was the Viking winter camp of 872/3 when several thousand men of the Viking army overwintered,” Mr Bott said.

Despite the work of Mr Bott and his friends leading to this historical breakthrough, nobody was aware of the significance of the dozens of small lead objects they also discovered during their years at Torksey, according to Nigel Mills, an artefact consultant with auctioneers Dix Noonan Webb.

“They thought they were lead weights, basically,” Mr Mills told The Independent. “The Vikings hacked a lot of silver and gold up into useable pieces, which had different weights, so they needed weights to decide [how heavy] they should be. However, when I weighed them, none of them matched - there was no consistency to them — and I thought it was very strange, but that was the theory at the time.

“It was only when I was in Oslo Museum that I realised they had two of these gaming pieces out of polished stone from this game Hnefatafl, which match the conical lead weights that Mick had. So I realised that there was a connection and I discussed it with Mark Blackburn at the Fitzwilliam and he agreed that these were gaming pieces.”

Mr Mills believes it is the oldest complete set of pieces ever found at one site.

“What’s really intriguing is when you think of the army of thousands of men, Viking warriors, all sitting around playing this board game. It’s really weird,” he said.

The purpose of the game is for the defender to move the king to one of the corner squares, which are designated as castles, as the attacker tries to surround the king on all four sides to prevent him from moving.

“It is a very strategic game, it’s like chess in the sense that you have to think about all the various lines of play — about what’s happening behind you, in front of you and to the side,” Mr Mills said.

“You have to think ahead and it is quite difficult to win by attacking … it’s very biased towards the defence, which is an interesting game for the Vikings to play — obviously they’re always attacking, defence wasn’t so important to them.

And with some of the kings sporting differing copper insets, Mr Mills posited a theory that these would act as prizes for the winner of the game, with soldiers aiming to collect as many different kings as possible.

The discovery will be auctioned online by Dix Noonan Webb on Tuesday, and is expected to fetch at least £1,000.

Mr Bott’s findings “show you how important metal detecting is and the significance of the things that they found", said Mr Mills, adding of the game pieces: “No one really appreciated them, but they actually are a very important part of our history.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments