Memorial sculpture at risk of crumbling away

As millions of Britons mark Remembrance Sunday, a desperate battle is under way to secure the future of a veterans' memorial.

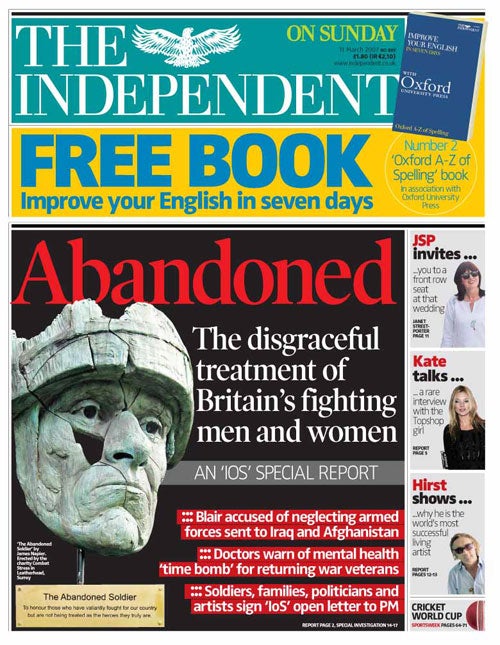

The 4.5 metre high sculpture of a soldier’s face, ‘The Abandoned Soldier’ was commissioned in 2007. The powerful and fragmented image became the symbol of this newspaper’s campaign, launched on 2nd September that year, to highlight the previously little-known military covenant and to call on the nation to honour it. Featured on the front page of the The Independent on Sunday, it symbolised a rallying call for better equipment of our armed forces in recognition of their willingness to make sacrifices up to and including laying down their lives.

But three years on the resin sculpture has yet to find a permanent home and campaigners fear it will disintegrate unless £75,000 can be found to cast a permanent, bronze version.

It stands currently at the National Memorial Arboretum (NMA), Staffordshire, where it featured earlier this month at the launch of new poetry book highlighting the plight of veterans suffering from post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Its creator, sculptor James Napier, teamed up with the book’s author Mark Christmas, a former serviceman turned PTSD campaigner, to lobby the NMA to allow the sculpture to stay.

“The sculpture was originally cast in resin which is already deteriorating, and unless we can raise funds to have it bronzed, it will eventually simply fade away. The symbolism is tragic,” he said.

Mr Napier described the sculpture as attempting to “portray a soldier physically and mentally broken…whilst revealing his inner strength and dignity."

It is modelled on Lance Corporal Daniel Twiddy, who suffered terrible burns after his tank was hit by friendly fire that killed two of his friends in Iraq in March 2003. He was medically discharged and suffered from PTSD.

Now married with a young daughter, the 30-year-old lives in Stamford, Lincolnshire, where he runs his own plastering business.

“Something as important as the Abandoned Soldier should be on permanent display - the National Memorial Arboretum would be a perfect home for it,” he said last night. “I’m sure it’s not too much of a problem for them to agree to that. Veterans are as important as the people that have died…the people that have been injured don’t tend to be remembered as much and I think it’s wrong really because they’ve been there and done it and they are here to tell the tale,” he added.

Speaking last month [Oct] Prime Minister David Cameron said helping veterans was a “priority” and added: “For many people, the mental scars that they have from the time they have served can be as serious, or sometimes even worse, than the physical scars, and we need to take it much more seriously as a country.”

Mental trauma can take years to become apparent, let alone be diagnosed and treated, and General Sir Richard Dannatt, the former chief of the general staff, has warned that thousands of veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan will develop mental health problems.

Yet the subject remains taboo in parts of the military, claimed Mr Napier: “Some people in military circles don’t want to accept that there is this problem.” And the past three years have seen him “hitting his head against a brick wall” in trying to find a home for the sculpture. “This might be to do with the powers that be who’ve decided that what it represents is a bit too controversial,” he added.

Citing a policy of “complete impartiality” a spokesman for the NMA would not be drawn on the merits of the memorial, but said campaigners would be “welcome to make a formal application to the Arboretum Trustees for a permanent site.”

A spokesman for Combat Stress charity paid tribute to the ‘Abandoned Soldier’ last night: “For some veterans it will be a natural rallying point while for others it will be deeply upsetting - but that is the power of this image."

Case study: the man behind the mask

Daniel Twiddy, 30. Now married with a young daughter, lives in Stamford, Lincolnshire, where he runs his own plastering business. He has been chosen as one of the finalists in the Barclays Trading Places Awards - for people who have triumphed against the odds. The winner will be announced at the end of this month

“Something as important as the Abandoned Soldier should be on permanent display - the National Memorial Arboretum would be a perfect home for it. I’m sure it’s not too much of a problem for them to agree to that.

The artist that did the sculpture did a brilliant job, I know it’s modelled on me but it doesn’t really look like me, it’s just the fact that it was modelled on an ex-serving soldier that was badly injured whilst fighting in Iraq.

Veterans are as important as the people that have died, they’ve gone out there and done the same thing, it’s just unfortunate that those that have died have died. The people that have been injured don’t tend to be remembered as much and I think it’s wrong really because they’ve been there and done it and they are here to tell the tale.

The sculpture is a rallying point for those that fell they’ve been forgotten and let down, everyone has their own memorials that they can go to and I think it’s a nice thing just to have somewhere where people can look at it, read about it and appreciate it.

Once it’s got a permanent place it can be promoted a lot better and people can learn a lot more.

The Royal British Legion and all the organisations, my regiment, the army have been brilliant, they’ve been very supportive and kind to me.

It is the MoD that are the problem. The army, my regiment, they’ve done no end for me and I still get invited up to the regiment and see them all and that, they are brilliant, and you talk to the MoD – the people sat at desk pointing fingers and I don’t feel they’ve got a clue.

The British army is one of the best armies there is, they train you well enough to go out and do things in places like Iraq and Afghanistan but I don’t think there’s enough training to readjust when you get home. I’ve got a friend that’s in the army still and he’s been out to Afghanistan twice and Iraq three times and he’s not quite right now, things are affecting him, you can see.

I got diagnosed with post traumatic stress disorder. I suffered a lot of burns and things: at the start your body’s more concerned with the physical side; you’re trying to repair yourself. once that’s better and the MoD look at you and go ‘oh well you’re alright now’, that’s when the mental side kicks in which no one can see. You start thinking about things and it’s not nice.

At the start I’d never have admitted to having PTSD, it’s sort of ‘I’m all right, shut up and get on with it’ sort of thing, I think there’s a lot of serving soldiers now that have got it but they don’t know they’ve got it.

The worst thing was the flashbacks and nightmares and things at the start. Now, it’s just things like if a firework goes off or the bang of a door and things like that, it just makes you jump and I’ve never been like that. When it happens you think ‘bloody hell don’t be so stupid’ then another noise will go off and you think ‘God I’ve done it again, why am I doing it?’ it’s strange…

I don’t really get a lot of flashbacks now, it’s been seven years and I perhaps get the occasional things – not so much a flashback, just when I will feel down all day and start thinking about my friends and the army life. I mean I’ve got an amazing life now, I’m married with a beautiful daughter and I wouldn’t ask for anything more, but you still have that feeling that ‘I wish I was still there’, or when you see the news on Afghanistan, ‘I wish I was still doing that’. The army is like a family, it’s a strange thing – it’s hard to explain…

The MoD side of things is still ongoing really; my lawyers in London are still trying to get a case together and trying to sort the MoD out which I can’t really say much about. For me it’s not about the compensation, it’s more about getting them to say sorry and accept liability and change the way things are done for the soldiers out there.

I don’t think the soldiers are paid enough for what they are doing out there. They are there fighting for a country and risking their life, they don’t get time off, they don’t get breaks and things, I think it’s disgusting really. There’s still a lot that needs to be done.

There needs to be better training to help soldiers adjust from coming back from these conflicts.

The army way of life is ‘get on with it, until your head’s totally screwed – we’ll sort you out then and get rid of you’ you’re like a number, they’re not bothered.

I cant fault the NHS, I’m entitled to priority treatment but I never take advantage of that, if I’m put on a waiting list I’ll just wait, because its still ongoing treatment on my face now – surgery and things to try and sort my face out a bit better.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks