Manchester Arena inquiry report: All the missed security opportunities before bombing that killed 22

Safety arrangements ‘should have prevented or minimised the devastating impact of the attack’, inquiry finds

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A public inquiry into the Manchester Arena bombing has identified “missed opportunities” in how security at the venue was set up.

Sir John Saunders, chair of the inquiry, said arrangements for the Ariana Grande concert on 22 May 2017 “should have prevented or minimised the devastating impact of the attack”.

“They failed to do so,” he added. “There were a number of opportunities which were missed leading to this failure. Salman Abedi should have been identified as a threat by those responsible for the security of the arena and a disruptive intervention undertaken.”

A report running to almost 200 pages has chronicled failures by British Transport Police, arena operators SMG and security firm Showsec.

Sir John identified five “missed opportunities”, and a possible sixth, where action should have been taken that could have dramatically altered the course of events leading to the deaths of 22 victims.

The report is the first of three volumes to be published by the public inquiry. It deals with the security arrangements at Manchester Arena.

The next part will consider the emergency response to the bombing and whether any of the victims’ lives could have been saved, and the final volume will look at Abedi’s radicalisation and whether the security services could have prevented his attack.

Manchester Arena’s security perimeter

The report identified a potential “missed opportunity” in the security perimeter around Manchester Arena, which did not encompass surrounding areas such as the City Room linking to Victoria station where Abedi struck.

At the time of the attack, the security perimeter was at the doors between the City Room and the arena concourse, meaning it was not until that point that tickets would be checked and large bags searched.

Sir John said SMG “should have sought permission from its landlord to push out the security perimeter before May 2017, so that people entering the City Room with large bags were checked before entry”.

“Had permission to push out the perimeter been granted, an attack in the City Room would have been much less likely,” he added. “Abedi may have been deterred from carrying out an attack at the arena. Had permission been refused, it is likely that SMG would have looked more closely at other threat mitigation measures required in the City Room.”

The report said that a wider security perimeter may also have caused the hostile reconnaissance Abedi carried out on 18 May, 21 May and on the afternoon of the attack to be spotted or made impossible.

The failure to recognise Salman Abedi’s return to the City Room as suspicious

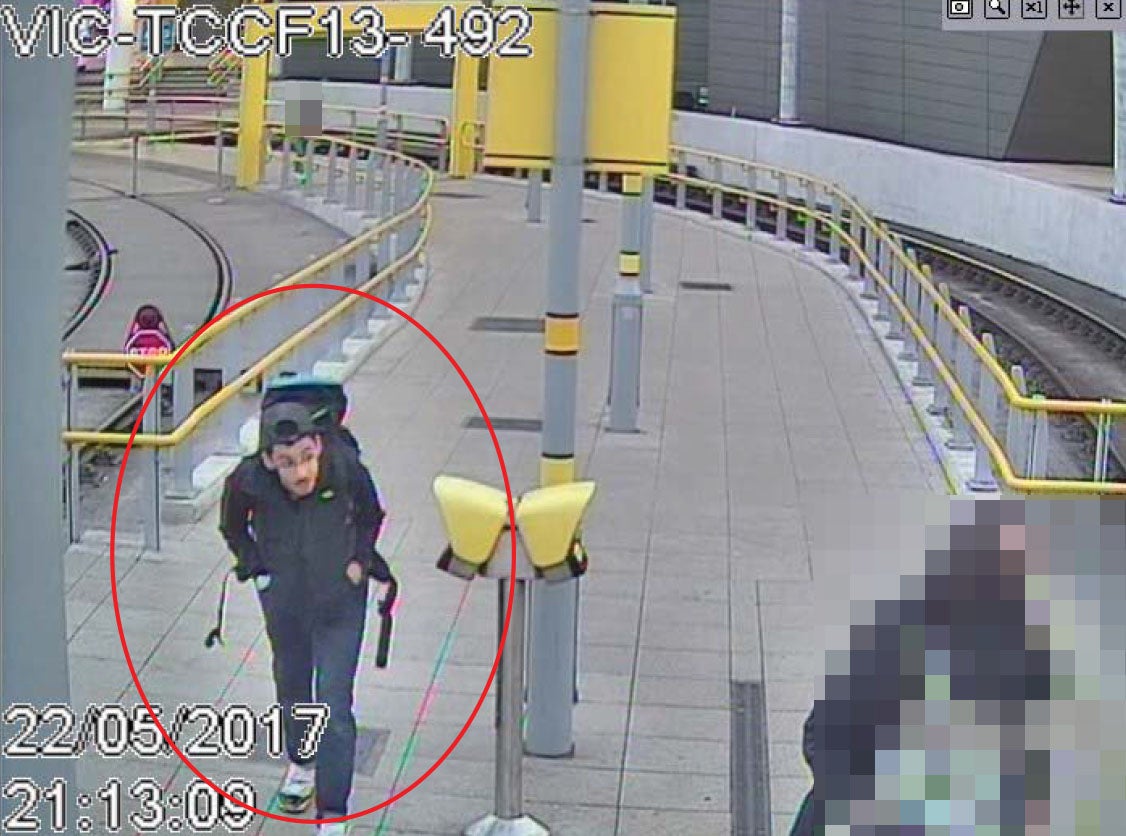

On the night of the attack, the bomber took a tram to Manchester Victoria station and arrived “visibly weighed down” by the 30kg backpack containing the bomb, overdressed for a warm evening and wearing a hat.

At about 8.50pm, Abedi spent 20 minutes in the City Room where he would later launch his attack, concealing himself in a CCTV blind spot that had not been addressed by SMG for several years.

Abedi left the City Room for a short time but remained in the station complex and then returned at about 9.30pm, returning immediately to the blind spot.

The report said Abedi’s return “presented an opportunity for him to be identified as suspicious” by Showsec security guard Mohammed Agha.

Mr Agha was 19 at the time and had worked for the company for a year.

“The fact that Abedi had been there previously was a factor which should have caused Mr Agha to pay him greater attention,” Sir John said.

“Abedi followed the same path in the City Room as earlier in the evening. He again concealed himself on the mezzanine in the blindspot. Had Mr Agha been more alert to the risk of a terrorist attack, he had a sufficient opportunity to form the view that Abedi was suspicious and required closer attention.”

Sir John said the security guard could have flagged Abedi to his supervisor at that point, adding: “Had this opportunity not been missed, it is likely to have led to Abedi being spoken to before 9.45pm.”

He said that if spoken to at that point, Abedi may have been deterred, may have left and tried to return later or may have blown himself up anyway, but “none of these possibilities is likely to have resulted in devastation of the magnitude caused by Abedi at 10.31pm”.

The CCTV blind spot

The report said that Abedi hid in a CCTV blind spot in the City Room for a total of one hour and 20 minutes on the night of the attack – initially for a relatively short period and then for the hour leading up to the bombing.

The terrorist is believed to identified the spot, on a mezzanine level with a good view of the arena doors, during hostile reconnaissance and deliberately concealed himself there.

“Abedi chose to hide in the area of the blind spot because it was the most obvious place to hide in the City Room,” the report said. “It was SMG’s responsibility to identify the existence of the blind spot and take steps to mitigate the risk it posed.”

Sir John said that security staff working at the arena that night were not aware of the gap in coverage.

He added: “Had the blind spot been eliminated either by increased CCTV or by patrols, [Abedi]’s activity would have been identified.”

The security check before Ariana Grande fans left the concert

The report said there was a further missed opportunity half an hour before the bombing, due to the “absence of an adequate security patrol by Showsec at any stage during this time”.

The company operated a system of “pre‑egress” checks, which involved a walk through the City Room.

The supervisor who carried out the check on the night of the bombing, Jordan Beak, said he spent about 10 minutes doing so at 10.10pm, but thought that the focus should be on keeping routes out of the arena clear.

CCTV showed that Mr Beak looked towards the staircases up to the mezzanine area where Abedi was waiting “very briefly” on two occasions.

“He did not consider them a very important part of the check because it was not an egress route,” Sir John said.

“Mr Beak did not go up on to the mezzanine area and so he did not see Abedi. This was a significant missed opportunity.”

The report said that if he had, Abedi would have been identified as suspicious and action could have been taken.

Sir John added: “I accept that Mr Beak was simply following the training he had been given in relation to the pre‑egress check.”

Christopher Wild reporting concerns about Salman Abedi

Sir John said the “most striking missed opportunity, and the one that is likely to have made a significant difference” was the point at which a concerned member of the public raised concerns about Abedi after challenging him.

Christopher Wild and his partner Julie Whitley, who was seriously injured in the blast, were in the City Room waiting to collect her 14-year-old daughter and a friend.

He told the inquiry how they had arranged to meet at the top of the stairs to the mezzanine level, and that Ms Whitley “didn’t like the look” of a man sat behind a wall with a large bag.

Mr Wild said the man now known to be Abedi appeared to be “keeping out of view”, which made him suspicious at a concert aimed at children.

He said he feared that Abedi could be a danger to children or “let a bomb off” and he resolved to talk to him.

“I asked him what he was doing there and did he know how bad it looked, him sitting there out of sight of everybody,” he added.

In a witness statement, Mr Wild described how Abedi did not reply when he asked: “What have you got in your rucksack?”

“He just looked up at me,” he added. “I then said, ‘It doesn’t look very good, you know, what you see with bombs and such, you with a rucksack like this in a place like this, what are you doing?’”

Mr Wild said Abedi initially said he was “waiting for somebody”, but then in response to everything else “he just kept asking what the time was”.

The interaction happened at about 10.15pm and after failing to get a meaningful answer, Mr Wild walked over to security guard Mohammed Agha to raise his concerns.

The report said he told Mr Wild not to worry and effectively “fobbed him off”. Mr Agha made “inadequate” efforts to flag down his supervisor or to pass on the report via a colleague who had a radio.

“This was a missed opportunity,” Sir John said. “Mr Agha did not respond appropriately because he did not take Mr Wild’s concerns as seriously as he should have. Responsibility for this rests on both Mr Agha and Showsec.”

Mr Agha’s report to his colleague

About eight minutes later, Mr Agha verbally relayed Mr Wild’s concerns to a colleague because he had no radio link to the security control room and did not believe he could leave his post, the inquiry heard.

That colleague, 18-year-old Kyle Lawler, said he initially was not suspicious about Abedi but did think there was something wrong, and that the bomber appeared nervous and fidgety.

“Mr Lawler felt conflicted about what to do as he had heard nothing of any potential attack,” the report said. “He stated he was fearful of being branded a racist and would be in trouble if he got it wrong.”

Sir John found that Mr Lawler had tried to use his radio to contact colleagues but that someone else was talking and he did not make “adequate efforts” to get through or contact a supervisor in another way.

“The inadequacy of Mr Lawler’s response was a product of his failure to take Mr Wild’s concern and his own observations sufficiently seriously,” the report added.

“Mr Wild’s behaviour was very responsible. He stated that he formed the view that [Abedi] might ‘let a bomb off’. That was sadly all too prescient and makes all the more distressing the fact that no effective steps were taken as a result of his efforts.”