Manchester attack: Salman Abedi ‘made bomb in four days’ after potentially undergoing terror training in Libya

Attacker reportedly met Isis militants linked to Paris attacks ringleader Abdelhamid Abaaoud

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Salman Abedi may have built the bomb that killed 22 people at the Manchester Arena in under four days, it has emerged amid reports he met Isis-linked militants in Libya.

Police said the attacker purchased parts for the bomb after flying back from the country on 18 May, while experts confirmed terror training would have enabled Abedi to build it in 24 hours.

The 22-year-old had made numerous trips to Libya after his parents returned to live there during the country’s bloody civil war, possibly fighting against Muammar Gaddafi’s soldiers alongside his father.

Islamist groups swiftly gained power in the conflict, where Isis has seized the opportunity to gain a foothold amid warnings the country could become a primary launch pad for terror attacks in Europe.

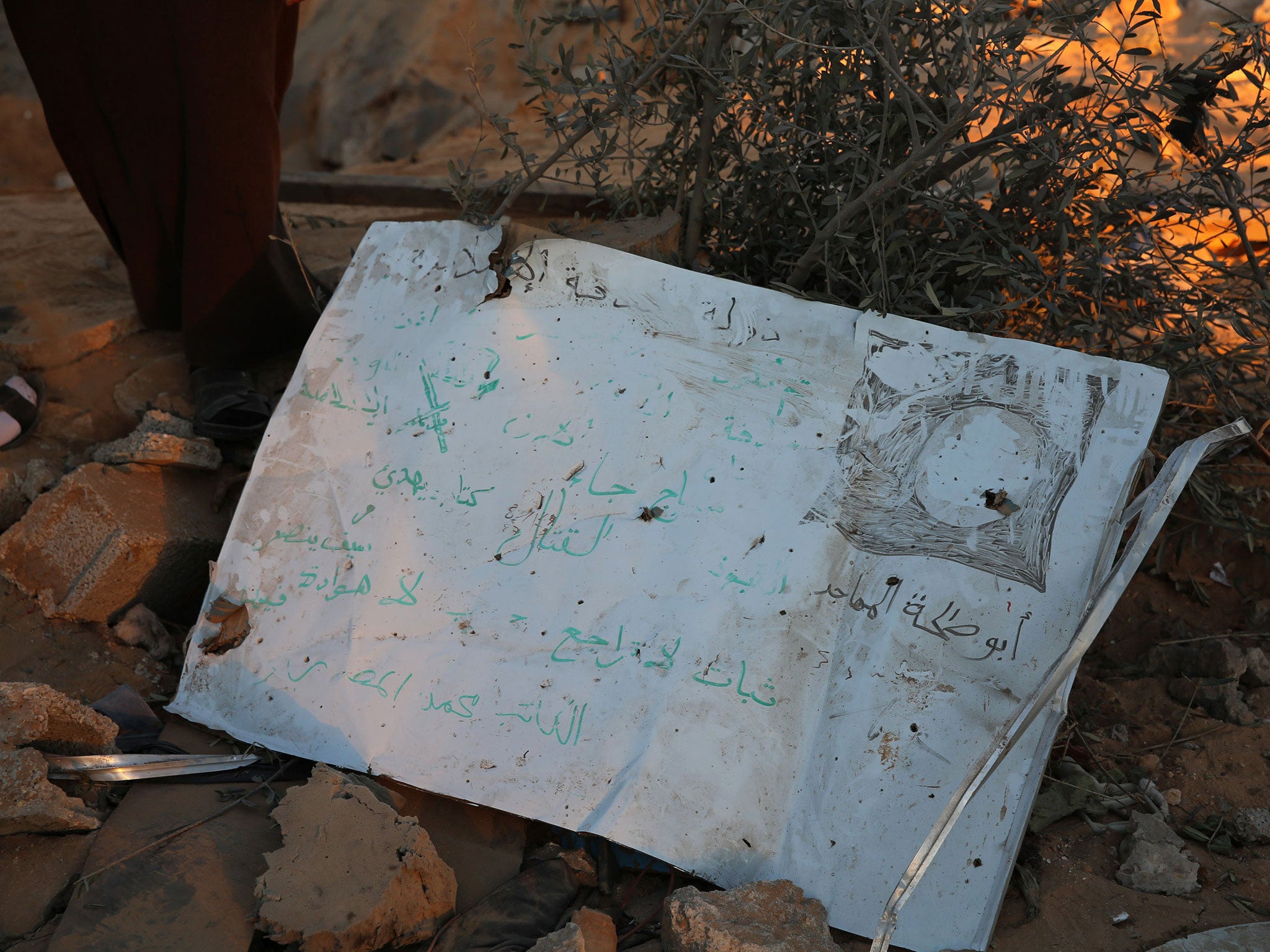

Among the countless militias battling in Libya is Katibat al-Battar al-Libi, an Isis special operations unit whose operatives are said to have met Abedi during his visits to Tripoli and the coastal city of Sabratha.

A retired European intelligence officer told the New York Times that Abedi kept in contact with the militants after returning to Manchester.

“When Abedi was in the UK, the contacts happened sometimes by phone,” he said. “If the content of the call was sensitive, he used phones that were disposable, or dispatches were sent from Libya by his contacts to his ‘friend’ - living in Germany or Belgium - who then sent it to Abedi in the UK.”

British intelligence agencies are working with their Libyan counterparts to piece together Abedi’s activities in the country, which is split between rival governments and thousands of militias.

Katibat al-Battar al-Libi was originally formed by Libyan jihadis fighting in Syria in 2012, and attracted Belgian, French and Tunisian foreign fighters.

Among them was the Paris attacks ringleader Abdelhamid Abaaoud, who was also linked to terror attacks at the Brussels Jewish Museum, the Thalys train attack and several failed plots.

Research by Cameron Colquhoun, the managing director of corporate intelligence consultancy Neon Century, found that many of the Battar brigade’s members moved back to Libya and set up terror training camps, focusing on mass murder, weapons training and bomb-making.

Among the terrorists to have gone through training by affiliated fighters in Sabratha is the Isis gunman who killed 30 British tourists on a beach in Tunisia in 2015.

Isis training camps used by “plotters actively planning operations against Europe” on the coast have been targeted by US air strikes, which have killed commanders.

The first concrete link between Libya and terror attacks in Europe came in December, when a failed Tunisian asylum seeker rammed a lorry into a Christmas market in Berlin.

Investigators found that the attacker, Anis Amri, had been communicating with Isis fighters in the group’s Libyan stronghold of Sirte using an encrypted messaging app.

Europol has warned that as the so-called Islamic State loses swathes of territory in Syria and Iraq, it will adopt new tactics to attack the West as defeated jihadis return home to Europe or move into other conflict zones.

“Libya could develop into a second springboard for Isis, after Syria, for attacks in the EU and the North African region,” said a report.

“Since mid-2015 Libya has become a major destination for Isis fighters in its own right and is believed to having become a hub for EU foreign terrorist fighters who, on returning to Europe, plan further terrorist attacks.”

Europol warned that jihadis in the country might have been driven out of Sirte but still possess stockpiles of weapons and “unlimited places in which jihadists could be trained for future terrorist attacks”.

If Abedi underwent terror training in Libya – or in Syria as some officials have suggested – he is likely to have been instructed on bomb-making.

Greater Manchester Police have said he made “core purchases” for the device detonated at Manchester Arena alone, and in the four days between when he flew back from Libya and launched the attack.

Like those built by Syria-trained Isis militant Najim Laachraoui for the Paris and Brussels attacks, the Manchester bomb used the homemade explosive triacetone triperoxide (TATP).

It has become a hallmark of Isis attacks and plots, being found mid-manufacture by supporters in Germany and France, and can be made cheaply from commercially-available chemicals.

Dr Sidney Alford, an explosives engineer, said making a lethal quantity of the explosive could take just 24 hours.

“It’s simple,” he told The Independent. “It takes only about a couple of hours to make, then you need to filter it and wash it and dry it.

“How long it takes to dry depends on your facilities but in a normal house with a radiator or something to stand it on, you could leave it overnight.”

Dr Alford, the chairman of Alford Technologies, said TATP is volatile and activated extremely easily, describing it as “sensitive”.

“I’m quite sure that a person who has been on a terrorist course will be instructed by people who will know how to arrange things so that the possibility of killing yourself [during manufacture] is quite low,” he added.

“I’m guessing that Abedi was given experience in doing it.”

He is believed to have packed the explosive in powder form inside a bag, surrounded by screws and nuts intended to inflict maximum death and injury.

Dr Alford said evidence from the scene of the blast suggested Abedi had a device to activate the bomb himself, but that there may also have been a secondary detonator capable of receiving a radio signal from a phone anywhere in the world.

The possibility would chime with Isis propaganda statements issued shortly after the attack, which claimed that a device had been remotely detonated and did not describe the atrocity as a suicide bombing.

Greater Manchester Police said Abedi made many movements alone in the four days between arriving back in the UK and launching the attack, moving around Manchester with a blue suitcase they are trying to trace.

A “significant” car was discovered in the Rusholme area, where he made several visits in his final days, was discovered on Friday, with a 24-year-old man being arrested.

Greater Manchester Police said he is one of 11 men, aged between 18 and 44, who remain in custody on suspicion of terror offences.

Officers have been stepping up security in the city ahead of a fundraising concert by Ariana Grande, who has visited fans injured in the attack in hospital.

Anyone with information is asked to call the anti-terror hotline anonymously on 0800 789321 or send images and footage to police by visiting the UK Police Image Appeal website.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments