Magna Carta: New research sheds light on the church's role in publishing world-famous charter

This week marks the document's 800th anniversary

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.New research suggests that Magna Carta may have been published predominantly by the church – rather than the Royal government of the day.

The revelations – announced as Britain prepares to commemorate the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta – shed remarkable new light on the politics behind the issuing of the charter.

The research suggests that early 13th century England’s King John was so reluctant to publicize the now world-famous document that the church had to step in to ensure that sufficient copies were made and distributed.

A new investigation into Magna Carta, carried out by scholars from the universities of East Anglia, Cambridge and King’s College London, has revealed, for the first time, that England’s bishops actually placed their own scribes inside the government’s civil service specifically to make copies of Magna Carta – so that every region of the country could have one.

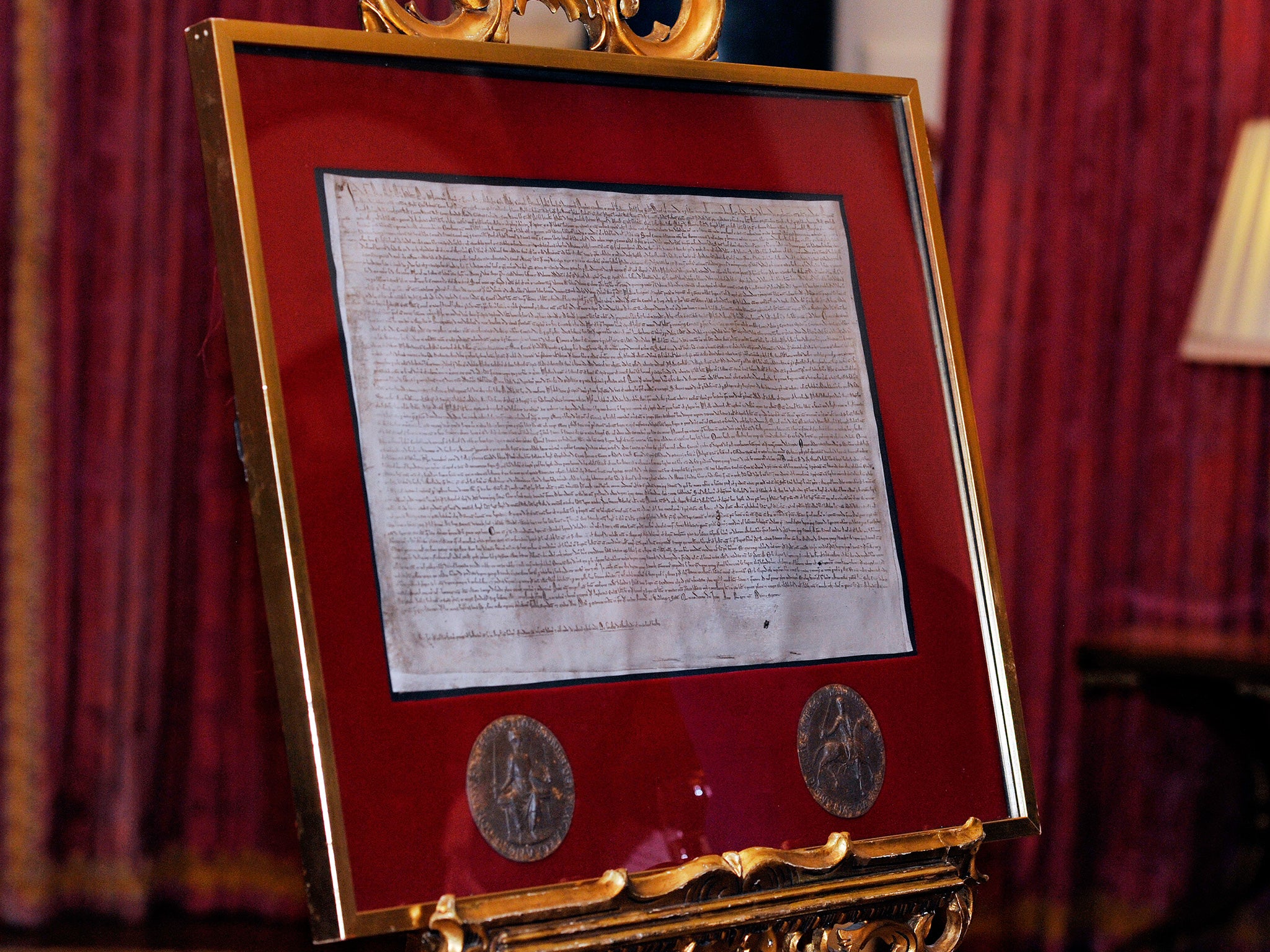

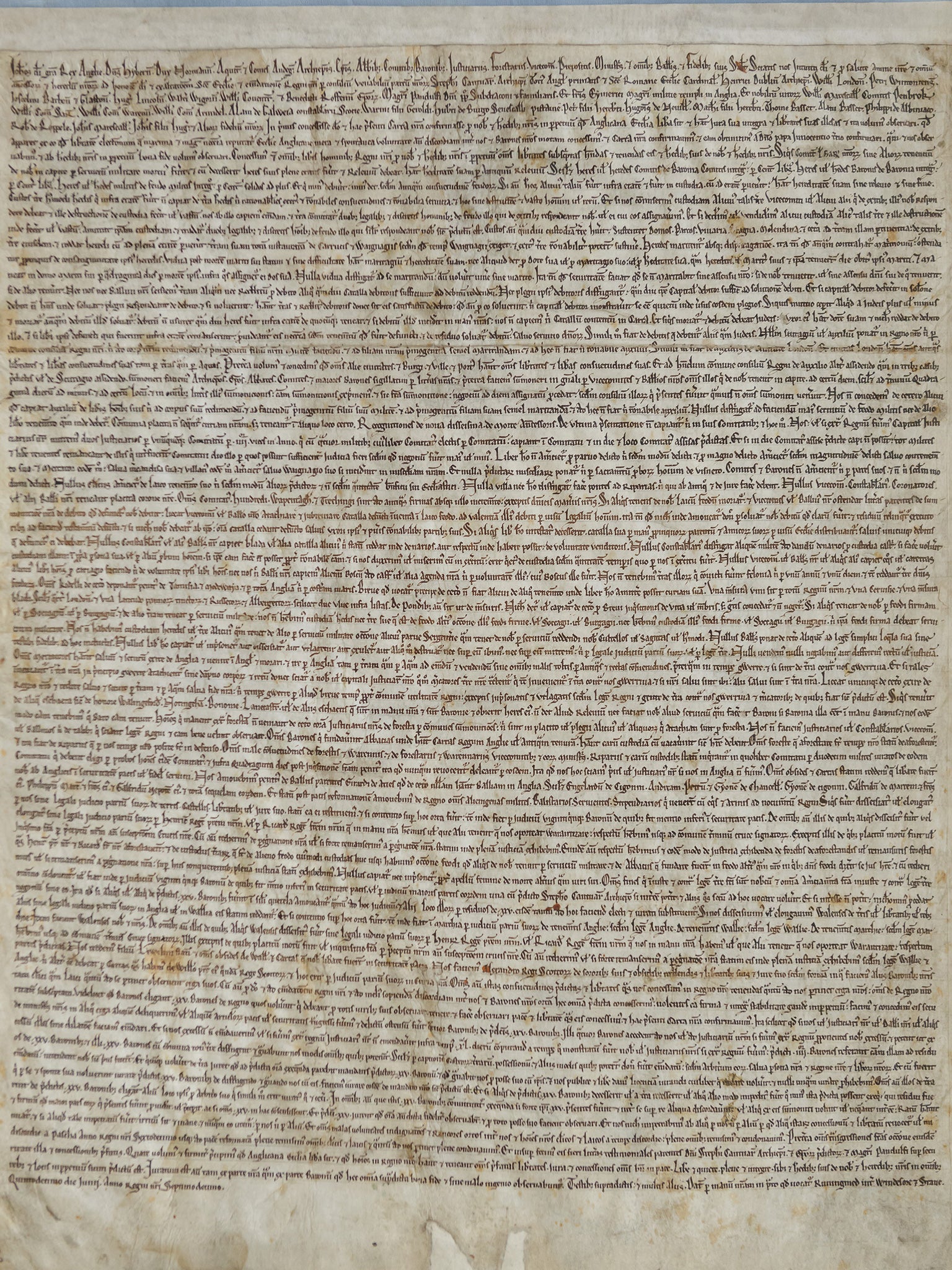

Only four original copies of the great charter survive – and the new research has now revealed that at least two of them were made by scribal representatives of English bishops, not by royal scribes.

What seems to have happened reveals King John’s reluctance to publicize what he had just been forced to agree to by the barons and bishops.

It had been the bishops who had been instrumental in bringing the king and the rebel barons together – and who had helped force the king to agree to and issue Magna Carta. The bishops had been present at Runnymede with the king and the barons during the negotiations there – and on 15 June, 1215 when the great royal seal was applied to the charter.

Now it seems that the bishops’ involvement simply continued – with their scribes being inserted into the royal chancery to ensure that the king did as he was told, that copies of the charter were made, that they were sealed with the royal seal and that they were then distributed.

The two copies that have so far been identified as having been produced by episcopal scribal representatives, inserted into the royal chancery, are those from Lincoln and Salisbury cathedrals.

The researchers – Professor Nicholas Vincent of the University of East Anglia and Professor David Carpenter of King’s College London – made their discovery by comparing the hand writing of scribes responsible for royal documents still surviving in English and French archives and ecclesiastical documents surviving in English cathedrals and in the National Archives.

The research has even identified the potential identity of the particular scribe who wrote Salisbury Cathedral’s copy of Magna Carta. The evidence suggests that he may well have been a senior clergyman at the Cathedral, William of Wilton who worked for the dean and chapter of the cathedral and potentially even for the bishop himself, Herbert Poer (or Poore), who had been involved in the Pope’s excommunication of King John.

Other recent research has also revealed that Canterbury Cathedral once had its own copy of Magna Carta. Professor David Carpenter of King’s College London has discovered that one of the copies of Magna Carta, currently held by the British Library, was originally the property of Canterbury Cathedral. Other research – by Dr. Sophie Ambler of the University of East Anglia – has revealed that another ecclesiastical institution, the Cistercian Byland Abbey in Yorkshire, also had one, probable given to it by one of northern England’s greatest medieval barons, William of Mowbray, one of the magnates who had forced the king to issue the charter.

The new research has “important historical implications,” said the University of East Anglia’s Professor of Medieval History, Nicholas Vincent.

“King John had no real intention that the charter be either publicized or enforced,” he explained.

“It was the bishops instead who insisted that it be distributed to the country at large and thereafter who preserved it in their cathedral archives,” said Professor Vincent.

He now believes that those aware of Magna Carta in the 13th century “would have seen not a royal charter, but something produced, published, preserved and even physically written by the English church.”

“What contemporaries would have seen in Magna Carta, both as texts and as physical artefact, was an ecclesiastical document.

“This serves as an important reminder of the ways in which our modern ideas of freedom, democracy and the rule of law emerged from a close co-operation between church and state,” said Professor Vincent.

King’s College London’s Professor of Medieval History, David Carpenter, believes that the new revelations are “exciting discoveries”.

“We now know that three of the four surviving originals of the charter went to cathedrals – Lincoln, Salisbury and Canterbury. Probably cathedrals were the destination for the great majority of the other original charters issued in 1215,” he said.

“This overturns the old view that the charters were sent to the sheriffs in charge of the counties. That would have been fatal since the sheriffs were the very people under attack in the charter. They would have quickly consigned Magna Carta to their castle furnaces.

“The church, therefore, was central to the production, preservation and proclamation of Magna Carta. The cathedrals were like a beacon from which the light of the charter shone round the country, thus beginning g the process by which it became central to national life,” said Professor Carpenter.

The new research has been funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

Magna Carta: Law, Liberty, Legacy - a unique exhibition on the great charter is being held at the British Library until September 1. Tickets £5-£12.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments