London riots, ten years on: ‘There was looting but it was a protest and we need to remember that’

‘The conditions that gave rise to unrest ten years ago are still prevalent today’, activist tells Nadine White

Anthony Smith* attended the UK riots of 2011 after being frustrated with being frequently stopped by the police.

“London was at boiling point; things had gone too far. I was getting harassed by police everywhere I went – it was humiliating, it was embarrassing; I was being stopped at shopping centres, high streets, main roads, in school uniform, during the weekend, everything,” the 28-year-old told The Independent.

“It was at the point where my mum was going to make a formal complaint to the local police station and I began writing down the badge numbers of police and community support officers and bringing it home. I used to have a stack of slips detailing the encounters.

“I started to experience the institutional racism (evidenced through encounters with police officers) as a young, Black male.”

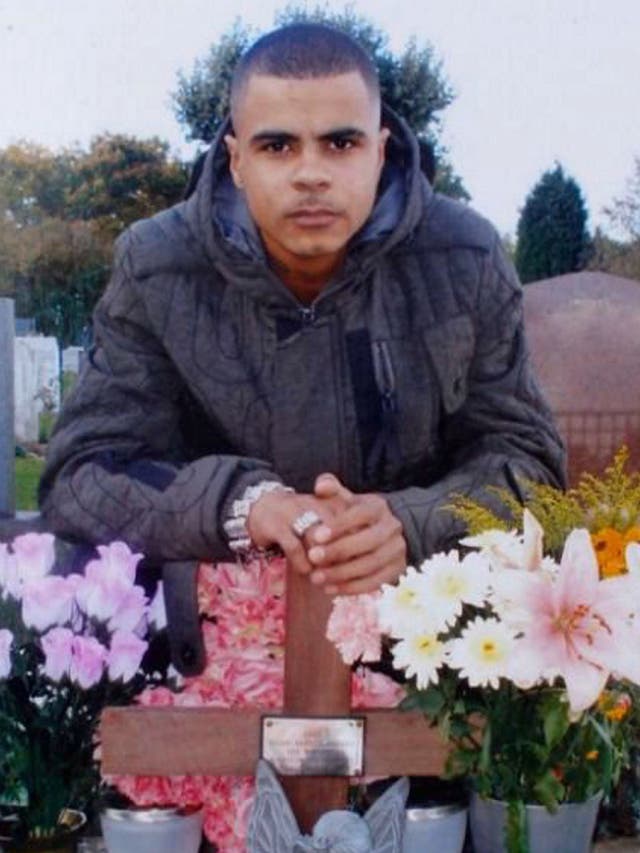

When Mark Duggan, a 29-year-old, unarmed mixed race man, was shot and killed by the Metropolitan Police in 2011, peaceful calls for answers went ignored.

The unrest that followed started in Tottenham, where Duggan grew up, and soon spread across the rest of the country in over 66 different areas including wider parts of London, Birmingham and Bristol; shops were looted, buildings set alight, stand-offs with armed police officers ensued.

Mr Smith described the chaotic scenes which unfolded in West Croydon and Brixton across south London; over five days around 15,000 people participated in the unrest, five people died and the financial cost to the country was around half a billion pounds.

“Everything was crazy, there were so many people, so much happening, so many sounds, different smells. The harm that came to people, there were really some long-term businesses that suffered, some went up in flames; those things are always unjustified and I’m not going to sit here and try to justify them.

“But you have to look at cause and effect. What leads to this happening in our society where people have no other way to make themselves heard to the point at which they have to go out and make a physical stand for what is right?”

Pointing to austerity, social deprivation and the rise in university tuition fees, Mr Smith said the atmosphere was thick with anger and resentment.

“It was a powerful moment for a place like the UK where people came together. We come together for carnival and for things to celebrate; but I don’t think, in my living memory, I’ve seen such a mass movement come together at a time (to tackle) some serious issues” he said.

“The media always focus on the people who were opportunistic; it doesn’t matter where you are, who you are or whatever you’re doing – there’s always people who are opportunistic. There was looting (...) but it was fundamentally a protest and we need to remember that.”

“More civil disturbances are almost certainly going to happen in the near future; all of the conditions that gave rise to unrest ten years ago are still prevalent today,” leading race equality activist Lee Jasper told The Independent.

“We’re going to have a tragic and completely avoidable repeat of history, given the deterioration of confidence in the police plus rising discrimination across a range of sectors like education, criminal justice, health and employment, which has been gravely amplified as a consequence of austerity.

“I’m deeply concerned about the fire next time.”

As Mr Smith echoed, the disturbances were also underpinned by a growing sense of frustration among Black communities around policing tactics namely stop and search tactics which disproportionately targeted Black men.

This was cited as a major source of discontent and many reported that these searches were often heavy-handed; figures at the time showed only about 10 per cent of more than a million searches led to an arrest.

Fast forward a decade and the new Beating Crime Plan (BCP) will grant police officers the power to stop and search people without reasonable suspicion in areas where serious violence could break out and roll out Section 60 orders with greater ease – a move that campaigners have called “ineffective and racially disproportionate”.

Moreover, the widely-contested Policing Bill will create legislation which allows police to create criminal offences for demonstrators who cause “serious annoyance.”

In the wake of the 2011 unrest, the then-government commissioned a Riots Communities and Victims Panel to investigate key issues around the event. Among other things, it recommended the Met improve their relationships with Black communities.

But little has changed. Now: trust in policing is 20 per cent lower in the Black population compared with the average while, just days ago, a Home Affairs Select Committee found that “unjustified” racial disparities in policing including recruitment and use of stop and search remain more than two decades after the landmark Stephen Lawrence Inquiry.

Around the time of Mr Duggan’s killing, ongoing cases of deaths in police custody rest heavy on the consciousness of Black communities around Britain.

For example, reggae artist Smiley Culture died from a single knife wound to the heart during a police raid on his Surrey home in March of the same year.

Over the ten years since then, more Black men have died in police custody including Dalian Atkinson, Kevin Clarke and Simeon Francis; fresh data from the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) said Black people are three times more likely to die following police contact than their percentage of the population.

Just weeks ago, the United Nations published a report which highlighted that in the UK, and globally, Black people have borne the brunt of racist state violence.

It is the view of the Network for Police Monitoring (Netpol) that conditions have worsened to some degree since the riots of 2011.

“In many ways, conditions that exist today in Britain seem worse than they were a decade ago before the riots in 2011. New police powers as a result of the Covid lockdown restrictions resulted in widespread abuse and the disproportionate targeting of Black and Brown communities,” a spokesperson from the organisation said.

“Even after around one in four young Black men were stopped and searched in London in early 2020 under the cover of the Covid lockdown – and even after Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests erupted onto the capital’s streets – the Metropolitan Police Commissioner Cressida Dick is still refusing to accept that institutional racism exists in her force.

“One east London police chief, Robert Tucker in Newham, has stereotypically stated ‘we stop a lot of Black children and young Black men because this is the high risk group’; the new Policing Bill, meanwhile, will massively expand the police’s ability to stop, search, and surveil people. As soon as the police get new powers, they abuse them. In this context, the new powers in this bill look like a powder keg.”

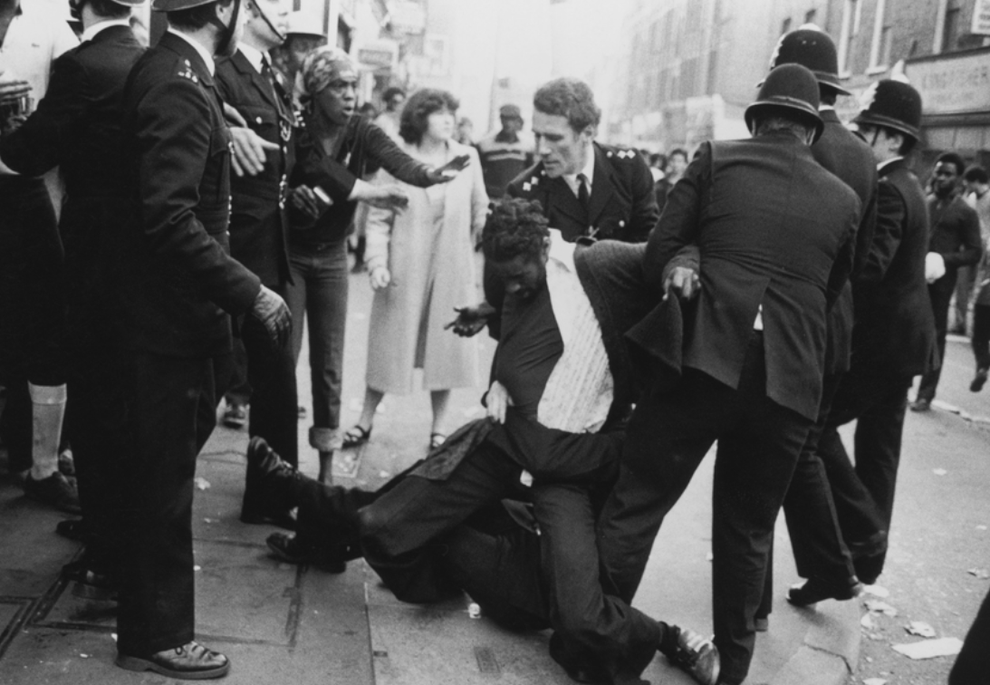

Speaking to The Independent, commentators have quickly drawn comparisons between today’s Britain, 2011 and 1981 which saw the infamous riots across Brixton and Handsworth, Birmingham.

Indeed, there are parallels between the “Sus” laws of yesteryear and the disproportionate stop and search rate within present-day Britain.

Moreover, just as unemployment among Black people was markedly higher than their white counterparts in April 1981 and 2011, recent analysis from The Independent of data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) recently revealed that the UK’s unemployment rate for Black people (13.8 per cent) is triple the unemployment rate for white people (4.5 per cent).

Referring to the 1981 unrest, the Netpol spokesperson added: “The police are just as violent (now) but even less accountable than ever, and their powers are rapidly expanding. Riots are never inevitable: they are almost always a reaction to a chain of oppressive choices taken by the police and the state. What is surprising about this is that neither the police nor the Government seems particularly inclined to care about the consequences of their decisions.

“At the same time, we face another decade of intensive economic hardship that will make life so much harder for everyone but the wealthy, yet this time is combined with the likelihood of a growing climate crisis.”

Based in north London, the 4Front Project is a youth organisation which “empowers young people and communities to fight for justice, peace and freedom”.

The initiative’s co-founder Temi Mwale explained that there’s still a long way to go in achieving justice for victims of police violence.

“Since the 2011 uprisings, the (police’s) so-called war on gang culture has had a detrimental impact on Black youth and really exposed our communities to increased surveillance, violence and systemic racism and abuse,” she told The Independent.

“You can track all of that back to the killing of Mark Duggan, and the ultimate lawful killing verdict which basically said that you can be shot by police while unarmed and that be lawful in this country.

“Policing is an inherently violent institution. Today, the fight to dismantle systems of punishment that inflict harm, trauma and pain on not just individuals but families and whole community, that goes on.”

But there are some glimmers of hope, some say. One commentator said the recent resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, following George Floyd’s murder, has seen progress in the anti-racism cause.

“Where there’s life, there’s hope; that’s the story of our journey as a people,” Mr Jasper said. “The struggle against racism is a bit like the stock market – it has its ups and downs – but continual resistance, engagement and mobilisation means that sometimes slowly, sometimes very quickly, we’re moving the dial forward.”

A spokesperson from Black Lives Matter UK said: “Today we see that Black Lives Matter protests emerging to resist the very same issues that we saw leading to the riots of 2011 because very little has changed in terms of state racism.; if anything things have gotten worse.

“But one thing that we do think has changed since then is the scale of youth-led resistance to racist police violence. The protests saw the emergence of Black-led grassroots youth organisations all over the country including Justice For Black Lives and All Black Lives Matter.

“It’s this strength of organising and action which can make us recall the events of 2011 not as a moment in history but as a continuum of Black struggle against police racism and violence.”

Deborah Coles, director at Inquest, said: “Ten years on we see the impact of growing racial and social inequalities and a culture of denial of systemic racism from an authoritarian government that wants to criminalise protest and bring in laws that will further exacerbate racial disparities in the criminal justice system. But we have also seen the energy of family and community justice campaigns and protests both to honour those whose lives were cut short and to demand structural change.”

Halima Begum, director of the Runnymede Trust, told The Independent: “Although structural racism and disproportionate socioeconomic inequalities are still prevalent and relatively unchanged in British society over the past ten years, what we have seen is a shift in Britain’s will to address disparities and host honest and open conversations about how to eradicate racial inequality.

“This week Abimbola Johnson, a highly respected barrister, was selected by the National Police Chiefs Council (NPCC) to lead an independent police oversight board, which has been welcomed by officers nationwide who themselves understand the urgent work that must be done to eradicate racist practices within the force.

“Rank and file police officers, businesses and the British public have all shown their commitment to the transformations that would eradicate structural racism. We now need updated policies to enable this shift. Such pragmatism would be a welcome measure to ensure confidence in a police service whose officers contribute enormously to society, but in which the faith of many minority ethnic Britons is still too frequently shaken.”

(*) This name was changed to protect the interviewee’s identity

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks