Lego legacy: The 26-year mystery of fantasy worlds lost at sea

The world’s oceans still hide the secret of millions of pieces – and one woman’s fascination with the miniatures became a global award-winning project that’s inspired a book and a film, writes Jane Dalton

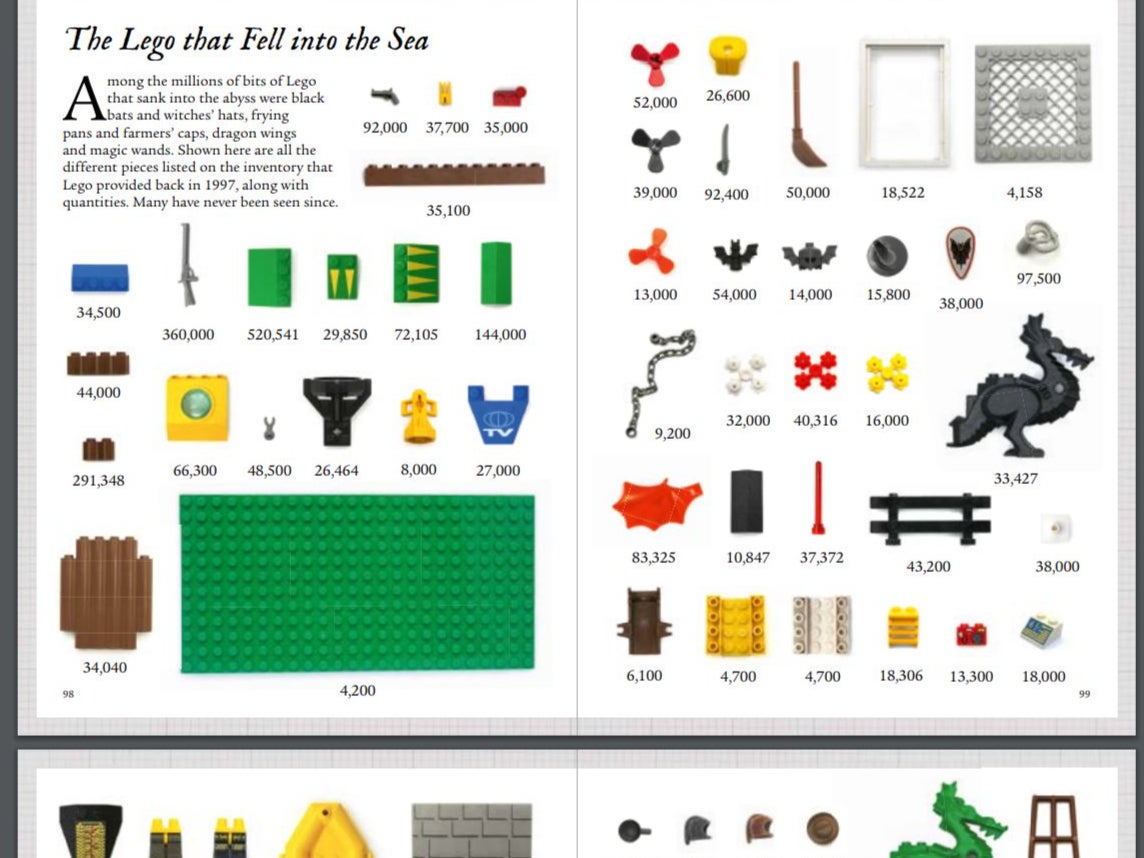

There are black bats and witches’ hats, brooms and frying pans, dragons and magic wands, monster feet and life rafts. There’s even a news crew.

It’s an array of random miniature objects, and together they make up a vast, fantastical, swashbuckling kingdom – but one that has been lost in the expanses of the oceans.

On 13 February 1997, a cargo ship heading from the Netherlands to the USA was hit by a freak storm wave off Cornwall, sending 62 crates crashing into the ocean. One contained nearly five million pieces of Lego, destined to be part of various brick sets.

They were being sent from the company’s home in Denmark, and as chance would have it, much of the Lego was sea-themed.

Only a fraction of the items have ever been recovered, and are still washing ashore to this day – not just in southern England, but also Ireland, Belgium, the Scilly Isles and the Channel Islands, and possibly as far as Australia and the US.

Thirteen years after the accident, Tracey Williams moved to Cornwall. Already a seasoned beachcomber, she started finding 3cm-4cm Lego pieces on the sand.

“I thought it was astonishing 13 years on that it was still washing ashore. So I set up a Facebook page to see who else had found the Lego pieces and where, and that’s how it all began,” Ms Williams tells The Independent.

As word spread, she began documenting pieces of Lego from the stricken Tokio Express, unaware then that her work would snowball into a globally recognised award-winning project, involving oceanographers, and inspiring a book, an exhibition and even a film.

For Ms Williams, a mother of four who is passionate about protecting marine life from pollution, the Lego spill became a full-time preoccupation.

Today the “Lego lady”, as she is known in Cornwall’s fishing villages, still meets trawlers as they come in, and it’s to her that fishermen report findings of Lego miniatures caught in their nets every week.

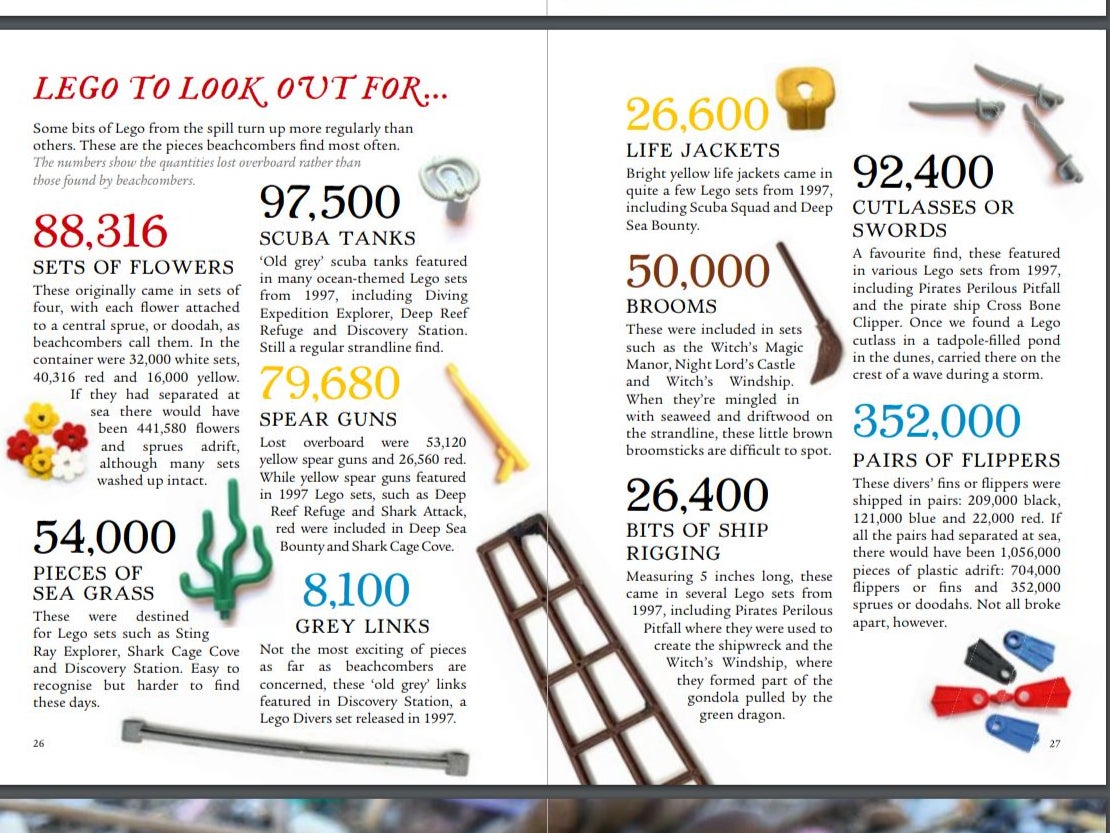

Few of the 4,756,940 miniature replica items lost to the sea were bricks; instead they include 352,000 pairs of divers’ flippers; 97,500 miniature scuba tanks; 92,400 cutlasses; 50,000 brooms; 88,316 bunches of flowers; 26,600 lifejackets and 26,400 pieces of ships’ rigging.

There were also 28,700 life rafts and more than 18,000 pieces for reefs and castle walls that featured in Lego sets such as Witch’s Magic Manor and Pirates Perilous Pitfall.

The 33,941 dragons have captured the imagination of many. Black dragons washed ashore in their thousands but only 514 dragons were green, and only a handful of those have been found.

The most coveted pieces, however, are black octopuses. Only 4,200 were in the cargo.

“It is said that octopuses are masters of disguise, blending into the background to escape detection. Lego octopuses are no different. When tangled in seaweed, they can be almost impossible to spot. I found my first Lego octopus back in 1997 but didn’t discover another for 18 years,” Ms Williams writes in her book, Adrift.

The “Lego lady” says judging how many Tokio Express Lego pieces in all have been found is impossible, because bits had turned up for years before she started logging them, while other pieces found abroad cannot definitively be traced to that container.

“Millions of pieces are still unaccounted for, thought to be lying on the seabed. These are the bricks or elements made of denser plastics, which don’t float, the ones thought to have sunk to the seabed,” she says.

One numerous find is white doorframes. But there were 51,800 sharks, none of which has ever been reported to her as found.

And then there’s the Crisis News Crew, a set released by Lego in 1997 including a cameraman, a female newsreader and two cameras. There were 59,500 pieces, but Ms Williams has only ever seen one.

Mini-flippers have been reported in Australia, although even with serial numbers it’s impossible to prove they came from the 1997 sinking.

Just this week, someone in South Carolina asked whether the Lego octopus his mother found on a beach there in the early 2000s could be from the spill.

For beachcombers, coming across a Lego piece from the accident 20 miles off Land’s End is like finding treasure, and some do a “happy dance”.

“One of my favourite finds was a little tiny tool wheel. Only one has ever been found, and I often wonder whether all the Lego men in the shipping container use them to escape,” Ms Williams says.

Scientists she has worked with have calculated Lego can last up to 1,300 years underwater.

Lego the company, which said it would love to turn back the clock to prevent the spill – although it was beyond its control, sent an inventory of the container contents to oceanographers.

One, Dr Curtis Ebbesmeyer, predicted at the time that ocean currents would carry the Lego past Norway into the Arctic Ocean and Alaska. Some, he said, might even reach Japan and across the Pacific Ocean to western Canada and California.

The Lego spill and other ocean plastics have come to dominate Ms Williams’s life. “I was fascinated by objects washed up by the sea and the story behind them,” she says.

“Every morning I check the tide times. I get up early and go to the beach at 5am then work around the tides, combining work and beachcombing.”

Asked whether pieces have become valuable mementoes, she says it’s illegal to resell them, as they must be reported to the government Receiver of Wreck.

Her Lego Lost at Sea project, which won the Rescue Project of the Year title in this year’s Current Archaeology Awards, is the subject of a new exhibition at the Royal Cornwall Museum.

While the Tokio Express limped back to Southampton for repair, the fate of the Lego container itself – whether it broke up or is on the seabed, still guarding its horde – remains a mystery.

Now Ms Williams is working with an independent film crew. “We’re interested now in finding out whether the container still exists. All the Lego pieces we’ve never seen. The 50,000 sharks, for instance – are they still trapped?” she says.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks