The human cost of cheap highs: a journey into Britain's most addicted city

Special report: Described by some as being more addictive than heroin, legal highs are not going to be legal much longer. And amid warnings a Government ban will only make things worse, Adam Lusher travels to Newcastle – the epicentre of Britain's growing addiction

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.James is pacing the room. He's agitated and suffering withdrawal symptoms from the newest drug in town that can turn him into “a bomb ready to detonate”.

“It’s called ‘Insane’,” he says. “Everyone’s on it, and it’s knocking everyone daft. Everybody’s like a zombie in the town.”

He's talking about the latest legal high – of many – to hit the streets of Newcastle. Because Newcastle seems to have become the epicentre of Britain’s legal high problem.

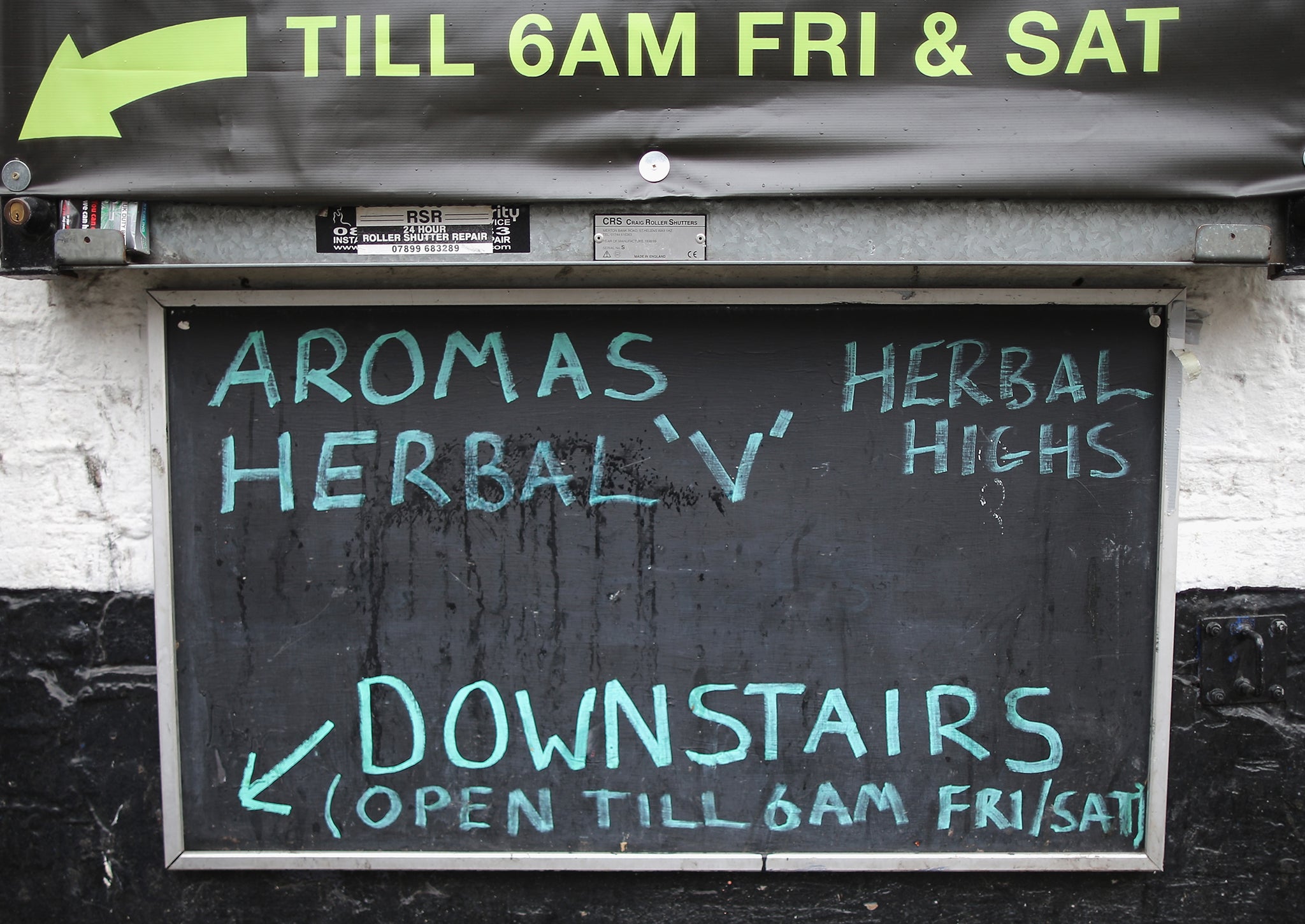

Designed to mimic the effects of banned drugs while sitting outside the scope of current drugs law, legal highs, known to officialdom as New Psychoactive Substances (NPS), can now be found nearly everywhere in the UK – sold in some of the country’s 250 head shops, but also online, in convenience stores and petrol stations.

In a bewilderingly short space of time, they have become a multi-billion pound industry. From almost nothing in 2008, within five years a total of 670,000 15 to 24-year-olds in the UK had snorted, smoked or swallowed a legal high at least once. And by 2013 the UK had, according to the UN’s World Drug Report, the largest legal high market in the EU.

And with fat profits for makers and distributors came an ever-rising death toll for users – from 10 legal high-related deaths in England and Northern Ireland in 2009 to 68 in 2012.

“It may be called fake weed,” insists Harry Shapiro, chief executive of the drugs information charity DrugWise, referring to synthetic cannabinoids, now probably the UK’s most commonly used legal high. “But it bears no relationship to the actual plant at all. This stuff puts you in hospital. It causes all sorts of mayhem.”

The active ingredient is sprayed on to plant matter and then packaged up and sold on, producing a potency succinctly described by Newcastle user Steven Southam, 31.

“It’s like cannabis,” he says, “With the effect of heroin.”

The only difference is that with legal highs, the effects can be so dreadful that heroin addicts switching to them as a cheaper alternative have been known to return to the Class A drug in the belief that, actually, it is the least damaging option.

Users talk of paranoid delusions, sudden collapses and “body popping” – fitting, with frightening regularity.

“Half those [ambulance] sirens,” says James, “Are for legal high heads.”

And there have been plenty of sirens sounding in Newcastle.

By 2015, according to a report by academics at Northumbria University, the Newcastle office of a national drugs agency was reporting a higher ambulance call-out rate for NPS-related incidents than anywhere else in the country.

“Professionals,” one Newcastle support worker told the researchers, “Are seeing this as a really serious epidemic.”

And James, 24, a homeless beggar with a long history of abusing other substances, could almost be the epidemic’s everyman.

Because you can forget about well-heeled clubbers – they soon worked out that legal highs were ‘cheap and nasty’ and spent their disposable income elsewhere.

In the words of one drugs worker based in the North-east: “It’s filtered down to the most vulnerable, the most ostracised.”

James, not his real name, started “chasing the buzz” after being introduced to legal highs by a 13-year-old.

Soon he was “waking up, taking a legal high, going to sleep, waking up, taking another legal high, going to sleep again. I wasn’t eating, I wasn’t associating…”

“I’m not allowed to see my three-year-old daughter now because of the legal highs,” he says. “I’ve been in and out of jail for the last three years because of legal highs.”

He finished his last jail stretch three weeks ago: “But I’ve had that much legal highs I can’t remember what the offence was. It would have been assault. Aye, my five previous convictions have been assaults. If I wake up and the legal highs aren’t there, I’m flipping, a bomb ready to detonate.”

While some users need two or three £10, 1g packets to get through the day, James says his daily spend can “easily” reach between £60 and £90. He can take up to 12g of Insane every day, not to get high any more, “just to keep myself on a level.”

He has been on cannabis, valium, drink “all sorts.”

“But the biggest addiction I have been through is legal highs. You can’t get out of it.”

Not even with prison detox.

“I’ve gone to jail and found there were more legal highs inside than outside.”

HM Inspectorate of Prisons found much the same thing, reporting in December that legal highs were now “the most serious threat to the safety and security of the prison system.”

Indeed, James’ story, told in the offices of The People’s Kitchen, a charity offering food and friendship to Newcastle’s vulnerable and homeless, holds no surprises for fellow users.

“I’ve seen kids this big using it,” says Mr Southam, indicating the height of a child who could easily be at primary school.

And 13-year-old boys introducing grown men to legal highs is no big deal. Even if that 13-year-old is now a 19-year-old user who, according to James, “has had two kidney failures off it and is walking round town like a little tramp.”

As for addictiveness, Kyle Rowntree, 23, may be clean now, but he can still recall: “I died off it. Someone had to bring us back to life with CPR. And as soon as I got out of hospital, I took some more. Even though it has killed me. Because that’s how addictive it is.”

Something, it seems, must be done.

And the Government is doing something. On 26 May the Psychoactive Substances Act will come into force, introducing jail sentences of up to seven years for anyone making or supplying any substance intended for human consumption that is capable of producing a psychoactive effect (with exemptions for alcohol, caffeine and tobacco).

Possession will not be an offence on the outside, but inside jail it could add a further two years to a prisoner’s sentence.

The act, Home Office Minister Karen Bradley has promised, will “end the open sale on our high streets.” It will send the clear message: “So-called ‘legal highs’ are not safe.”

And yet.

Not everyone is entirely convinced – although it will certainly help Government ministers look tough on drugs.

“Politically, they are low-hanging fruit,” says Harry Shapiro. “The easiest thing for any Government to do is to stop people buying these things from shops next to Mothercare. But don’t imagine it’s going to solve the problem.”

Or, as James puts it: “100 per cent, people will carry on dealing and taking.”

It’s just that when it comes to the sellers, the local head shop owner might be replaced by the neighbourhood crack dealer. As experience already suggests.

Police forces have already used anti-social behaviour legislation and Trading Standards officers have already used existing consumer safety regulations to stop shops selling legal highs - to such an extent that critics claim the new act is unnecessary, in practical, if not political terms.

In Blackburn, Lancashire, for example, the local authorities persuaded head shops to stop selling legal highs in late 2014.

The result, according to Professor Fiona Measham, of Durham University, who researched what happened next, was that “Synthetic cannabinoids shifted from head shops to being sold by the local crack dealer – a particularly obnoxious character who sells to any age, offering small pocket money’ deals.

“Young people were stealing their parents’ clothes in exchange for synthetic cannabinoids. The homeless were selling hostel bedding.”

The crack dealer was eventually arrested, but, Prof Measham says, his actions showed that: “Whatever you think of head shops, I don’t think any rational person would consider moving from them to street dealers a good result.”

Newcastle, too, has stamped out the head shop and convenience store trade. In January, Newcastle Police teamed up with trading standards to establish a NPS Task Force.

“You used to see drugs, drugs, drugs,” says James. “Now the shops have been closed down.”

But where there is a will and an addiction-driven market, there is a way.

“It’s [still] in Newcastle,” insists James. “Big sources are coming through with it, big packages, boxes and boxes and boxes…”

Perhaps tellingly, he refuses point blank to comment on who these new kingpins of Newcastle’s legal highs trade might be. But he does add: “I’ve heard lots of people say that’s where the money is. [Because] everyone is on it now.”

It's a view that is pretty close to that of Professor David Nutt, former Government drugs tsar and outspoken opponent of the Psychoactive Substances Act.

“The contents of the head shops will be brought up by black market dealers, and on May 26 everything will be underground.”

It might, for now, be impossible to say whether Professor Nutt’s prediction will prove accurate - but it is striking how many UK legal highs websites now carry slogans like “Stock your favourites for the last time.” Perhaps helpfully for the black market dealer, they are also offering “huge discounts when you bulk buy.”

Professor Nutt talks of the creation of “a scary market”, of head shop owners being replaced by ruthless street dealers eager to get legal highs customers on the more profitable crack and heroin.

He cites the example of Ireland, which banned legal highs in 2010. After the ban closed the head shops, one user told the BBC: “People started selling it on every street. It was even easier to get.”

European Commission figures suggest that post-ban, between 2011 and 2014, Ireland experienced Europe’s second largest increase in legal high use among 15 to 24 year-olds.

In December, Ireland’s own National Drug-Related Deaths Index showed that the number of drug poisoning deaths in which legal highs had been taken (sometimes with other substances) increased from 6 in 2010 to 28 in 2013.

Those policing the streets of Newcastle, however, disagree. Strongly.

Superintendent Richard Jackson, of Newcastle’s NPS Task Force, scathingly dismisses the “myth” of the relative safety and caring hippy ethos of head shops.

“The loving attitude of the head shops,” he says. “We didn’t see it.

“One or two might have shown some duty of care, but not around health risks. It was just age or wanting a clientele that wouldn’t cause them problems. Their overriding motive was commercial benefit.

“They were selling products that they knew were putting people in Newcastle close to death’s door. We were getting calls to collapsed 14-year-olds.”

It’s certainly hard to get dewy-eyed about some of Newcastle’s former legal high outlets. One convenience store was, according to the owner, selling only to adults seeking “relaxation”, but was doing so opposite a primary school. The local newspaper reported emergency services being called to the area 90 times in one week to deal with people suffering the effects of legal highs.

So if Superintendent Jackson admits that “what’s been left behind is the traditional back street network of drug dealers,” he’s also adamant that: “Taking away the head shops has not made things worse.”

He says Newcastle’s rate of ambulance call-outs to legal high-related incidents has dropped from 297 for the month of January, when the task force was formed, to about 100 every 28 days – roughly what you would expect for other drugs like heroin or cocaine.

As for fears about street dealers luring users into trying cocaine or heroin: “Legal highs are far worse, far more addictive.”

At the People’s Kitchen, when James finishes telling us about the misery inflicted by Insane, we get yet another glimpse of how bad those bad experiences can be.

A healthcare worker, we learn, has visited to collect some toiletries for a man in his twenties, a legal highs user, who has just been sectioned.

“It’s definitely hurting us,” agrees Mr Southam. But no ban will stop him using.

He shrugs, wearily.

“There’s always going to be something that kills you.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments