Karma Nirvana: Spending a day at the helpline advising terrified girls being pushed into forced marriages

'If it was a British white woman it was happening to, they wouldn’t bother with the word ‘culture’ - they would just say ‘abuse’'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The email was made up of just one line: “I need help asap please : (.”

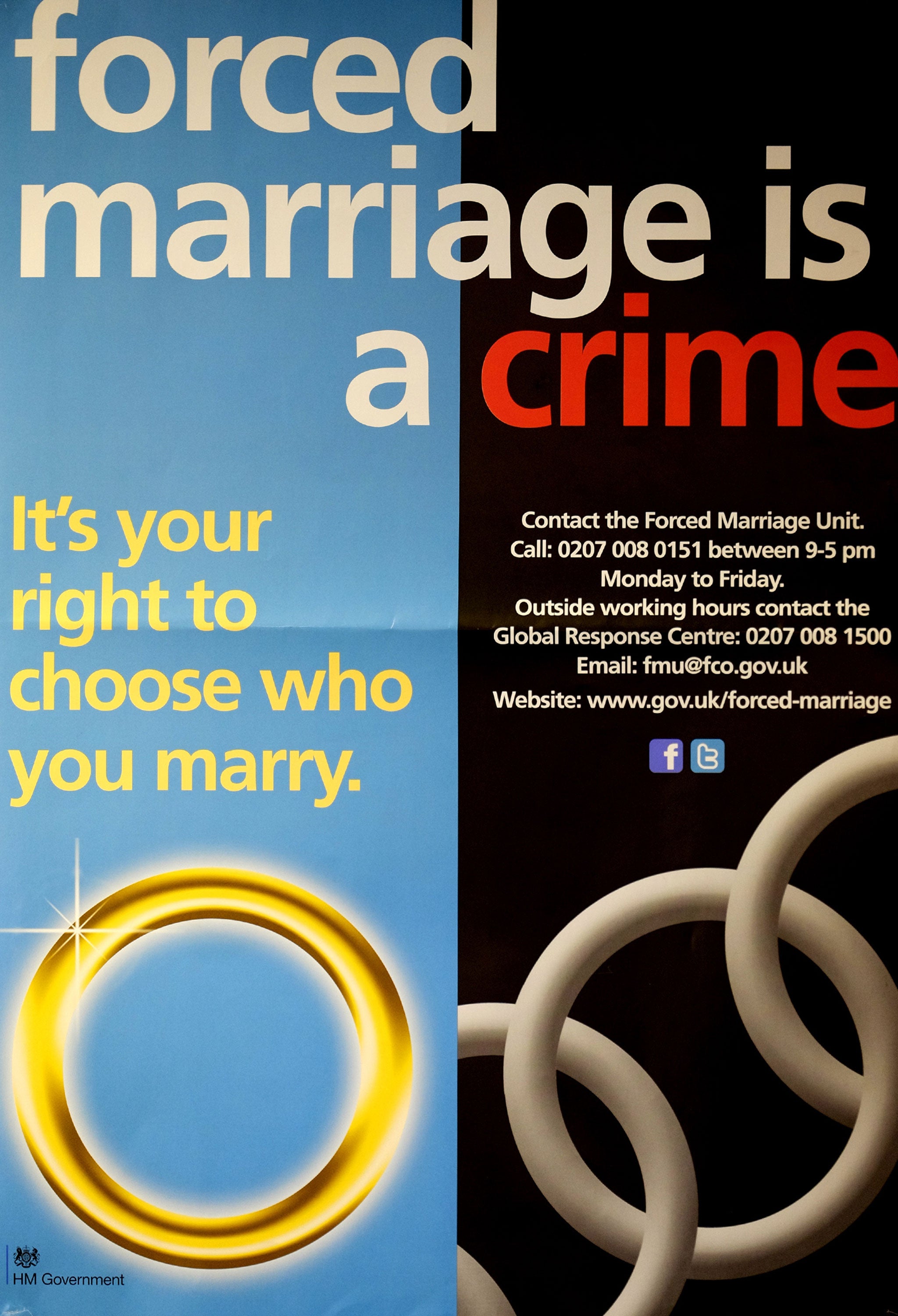

It was the first of many messages sent to the forced marriage and honour abuse charity Karma Nirvana from a teenager desperate to escape home. Over the past few months, in snatched one-line messages – “can’t stay at home any more. Losing the plot” – she has tried to plan her escape with staff at the helpline.

In her chain of emails, she has claimed to be a “punch bag” for the family and expressed fears that her parents will “send her away to get married or worse” if they knew she was planning on fleeing.

When The Independent spent a day at the helpline this week, the young woman was finally able to make telephone contact, sneaking a few seconds alone while her family were downstairs. Softly, she asks if the charity has been able to find a refuge for her in the city she wants to move to. The answer is no: all places are full up for the second day in a row.

The teenager is encouraged by the call handler to try for a refuge in another part of the country but is frightened of going somewhere completely unfamiliar. In the end, she says she will call back – but doesn’t. She will probably call again the next day to see again if a new place has become available.

It had taken her months to get to this point. She has worried about not being able to see her nephew any more – “He’s the only one that loves me; this is harder than I thought,” she wrote in one email. In another, she described her fears that it would be a “big sin in Islam” if she cut ties with her family.

In the top floor of a non-descript terraced house in Leeds, three call handlers sit listening to people unburden their pasts, helping them plan urgent escapes for their future. The small team dealt with more than 8,268 calls for help last year – almost double the number in 2010.

Priya Manota, the helpline manager, says: “It’s been busy here the past couple of weeks because of the start of the summer holidays. We had 57 calls in a day last week. Sometimes, if someone calls for emotional support, it can take an hour or more, but then you’ve still got to help people needing emergency refuge that day.”

Anna Kaur, who normally works in schools training staff to detect honour abuse and forced marriage, is chipping in for the summer holidays. She takes a call from a teenager, who initially seems just to want to know about the charity, asking: “What is this helpline, then?” and “What is honour-based abuse?” But it quickly becomes clear that her interest is not academic. For more than an hour, Ms Kaur listens patiently as a pattern of family control and abuse spills out.

She describes her Bengali father finding mobile phone pictures of her at a dance with her hair down (she normally wears it up in a hijab) and losing his temper. She is constantly being watched – she was chaperoned from college and once when she came back in the evening on the bus alone, a Bengali man she didn’t know spotted her and told her father, who was furious.

She has a male friend and is worried that, if her parents find out how close they are, she will be forced to marry straight away. Marriage is something they always said they would choose for her but she thought she had more time. As the conversation comes to a close. she apologies. “Sorry I’ve been talking so long,” she says, “It’s the first time I’ve been heard.”

Hanging up the call. Ms Kaur says she is pretty sure there is more to the story: “We’re building trust now, but there could well have been violence. I think she’ll call back... another time.”

Sometimes it’s professionals who call the helpline for advice. Earlier this month, a 16-year-old girl who had been assaulted by her father in an honour-based attack and taken into foster care was about to be sent back to the family home and was terrified.

Her father had threatened to force her into marriage or kill her, but the social workers were still pressing ahead with a court hearing to send her home. After a volunteer working with the student called Karma Nirvana for advice, the charity intervened and the court case was scrapped.

Sofina, the call handler who dealt with it, says the disturbing thing with that case, and many others, is the fear from professionals of causing offence. “They didn’t see it was high-risk even though there had been threats to her life. This volunteer said to me: ‘I don’t know culturally what I should say. I don’t want to offend anyone.’ It’s always the word ‘culture’ that they use.

“If it was a British white woman it was happening to, they wouldn’t bother with the word ‘culture’. They would just say ‘abuse’.”