Junior doctors dispute: Five go to war with the Government

On 19 and 20 September, a group of five junior doctors called Justice for Health will be taking on the Government in the High Court. Youssef El-Gingihy hears their stories and how they are coping in a world in which ‘nobody tells the truth’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

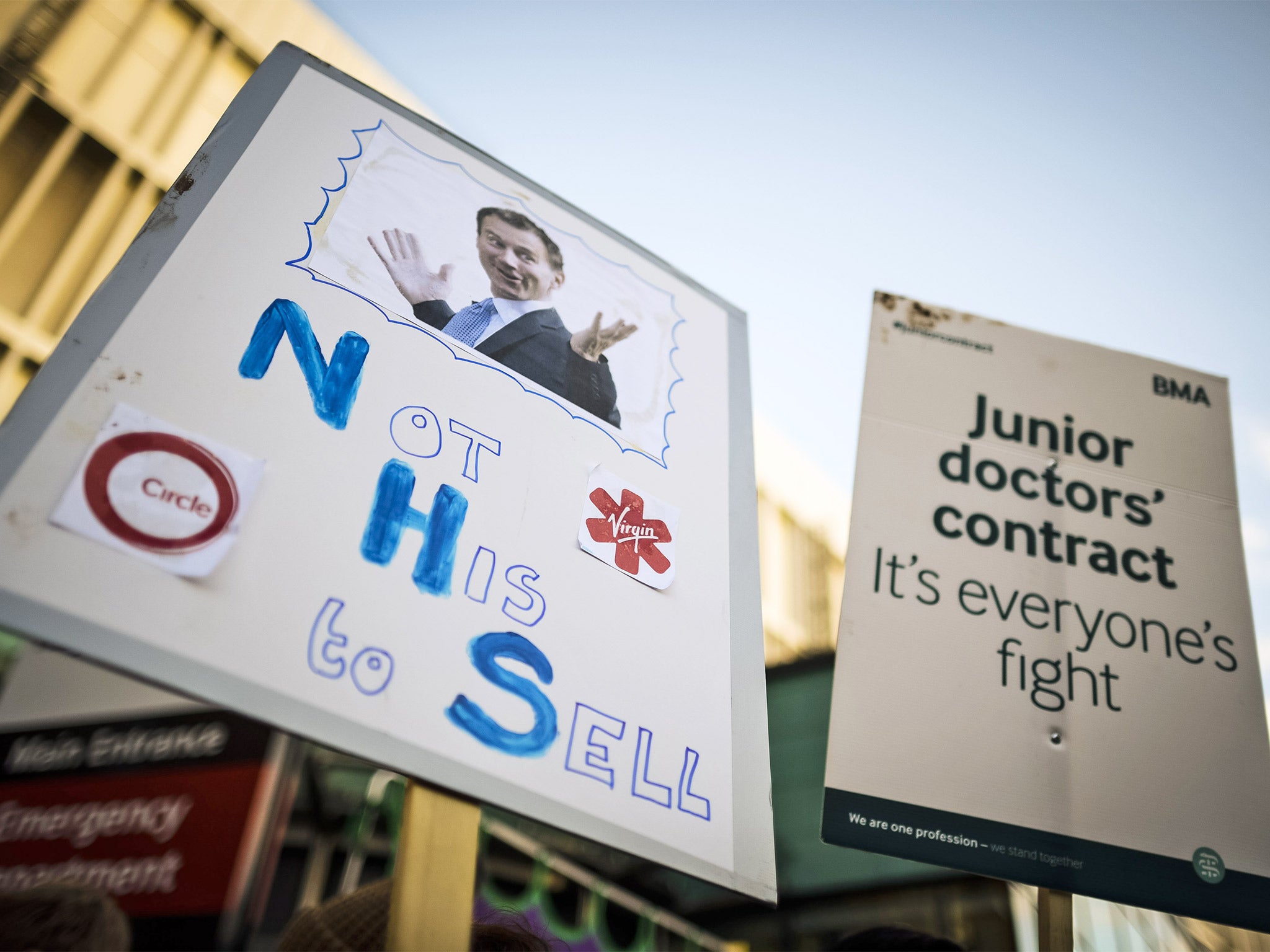

Your support makes all the difference.We are approaching a year since the junior doctor movement kicked off and it is showing no signs of running out of steam. The BMA held a referendum on an amended contract at the end of June. Admittedly, you may have missed this as it was eclipsed by another referendum around the same time. Nearly sixty per cent of junior doctors voted No (to the contract) although this was not exactly a surprise. Jeremy Hunt has effectively stated that he will now enforce the contract.

The BMA has escalated industrial action with a series of unprecedented rolling strikes. There is also the looming threat of further strikes from teachers, rail workers and fire-fighters. The Times and the Daily Mail have gone on the attack describing how “militant” and “radical” trades unionists are bent on toppling the Conservative Government. The more plausible explanation is that public sector workers are uniting against Conservative austerity policies.

On 19 and 20 September, a group of five junior doctors called Justice for Health will be taking on the Government in the High Court. The Justice for Health doctors are Dr Ben White (a medical registrar), Dr Nadia Masood (an anaesthetics registrar), Dr Francesc.a Silman (a GP registrar), Dr Marie-Estella McVeigh (previously an obstetrics and gynaecology doctor but is now training to be a GP) and Dr Amar Mashru ( an A&E registrar). Remarkably, the “NHS five” – as they may come to be known – did not know each other well prior to this. They now describe themselves as “a dysfunctional family” with Amar as the “disapproving father”.

Justice for Health has brought a judicial review over the Government’s right to impose the new junior doctor contract. David versus Goliath comparisons instantly spring to mind.

I meet Ben and Nadia at a central London hotel. Ben shot to fame when he resigned his job live on Good Morning Britain with Piers Morgan and Susanna Reid. It certainly made for a sensational exclusive – Jeremy Hunt was pushing junior doctors over the precipice. And he is not alone. Polls suggest that the new contract could lead to an exodus of doctors.

Ben is softly spoken. He comes across as thoughtful and considered. I get the impression that he deliberates over each phrase. He intercalated in law and ethics, which probably goes some way to explaining this. He confesses that his scepticism sometimes brings him “to the point of paralysis”.

A Manchester United fan born in the city, Ben’s family moved around constantly when he was young. His father is a TV soap director currently with EastEnders, while his mother is a documentary executive producer behind the 35 Up and 42 Up series.

I reckon that the movie star most likely to play him would be Hugh Grant – although as Ben points out, he is 33, single and living with his mum. So I guess it would be more the tentative Hugh Grant of Four Weddings and a Funeral rather than the dashing cad of the Bridget Jones movies.

Nadia carries herself elegantly and has unnerving poise. She candidly admits that she did not have “a political bone in her body”, describes herself as an Essex girl and confesses that she watched trashy TV and enjoyed “living in her bubble”. When she was very young, her family moved to a village in rural Essex, where “not a lot happens”. She attended a Catholic convent school which instilled in her an industrious work ethic.

Her father was self-made. But when Nadia told him that she wished to study medicine, he was not exactly enthusiastic. He worried that it might not suit her temperament as she enjoys her life outside work. Nadia was adamant, though, and went on to study at St George’s medical school in London. The transition from village life to a global capital was certainly a culture shock.

I start by asking them whether the prospect of taking on the Government is terrifying. Nadia replies that it is best not to think about the magnitude of the situation, comparing it to running a marathon in that you only look back at the end.

Justice for Health has demonstrated a remarkable aptitude for fund-raising through the legal crowd-funding site CrowdJustice. At the outset, Ben confidently informed Julia Salasky, the founder of CrowdJustice, that they intended to raise £100,000. He was politely informed that the most anyone had previously managed was in the region of £30,000. They smashed this record by raising £50,000 in the first 24 hours and had reached £100,000 by day 4. As they humbly point out, it just goes to show that there is a remarkable groundswell of public support for junior doctors. It’s also a stark reminder that legal aid cuts have reduced access to justice.

So what was the motivation behind the judicial review? Ben states it is about wanting to live in “a proper society”. It comes down to “"basic things, such as truth”. Nadia tells me it is about fighting something “immoral and unjust... you cannot treat people that way”. In effect, it comes down to a fundamental sense of decency and fairness.

As Ben puts it, it is actually quite straightforward: either policy making is carried out in consultation or it is PR and spin. If we live in a democratic society, Nadia explains, then government should respond to questions posed by front-line NHS staff. It is a reasonable position by any standards.

They are confident that the truth will emerge. In recent months, the Government’s case has been severely damaged by various leaked documents, including the Government’s risk register, which concluded that the 7-day NHS plan is not feasible with current funding, resources and staff.

Ben describes the collision between his training as a doctor and the world of politics. In medicine, probity, honesty and integrity are paramount. It has been eye-opening, he says, to encounter “a whole, new world” in which “nobody tells the truth ... nothing is as it seems ... evidence does not mean anything”.

It is clear that the junior doctor body has been on a steep learning curve. As with the miners’ strikes during the 1980s, they are up against the forces of global capital. Ben frames it as an evidence-based scientific approach versus an economic and political ideology.

A whole generation of doctors has been politicised. Previously, Nadia admits that she felt she did not have any power to influence events. Ben remembers how politics was virtually a taboo subject at work until the strikes commenced. Nadia has worked in jobs with rota gaps while Ben believes that hospitals are falling apart due to underfunding and a lack of staff.

Both are also aware that this is not just about the small print of a contract dispute. I can only agree – the contract is about lowering the wage bill to facilitate privatisation. “The most important thing is not that this hospital saves x-amount of money... it’s that people get seen and it is provided by the state and they do not have to pay,” Ben declares.

There are over 50,000 junior doctors. But only five are taking a leaf out of Mr Smith Goes to Washington and taking the Government to the High Court. How did it all start? Apparently with a tweet, as tends to be the case in the 21st century. The response was staggering. Before they knew it, a meeting had been arranged with “some of the top QCs in the country” in this field. “It was amazing,” recalls Ben, because they did not know if anyone would even turn up to the meeting. He still remembers the dramatic moment when he instructed Saimo Chahal QC like something out of a John Grisham movie.

How did they come by the name of Justice for Health, I wonder? They regale me with how “alternative peer” Lord John Bird, founder of The Big Issue, arranged a meeting in the House of Lords. Three of the group went along, even though only Ben was on the list, and they somehow managed to wangle their way in. Lord Bird inspired them to come up with the name.

This story seems to encapsulate the plucky spirit with which they have approached everything. The journey has taken them to the heart of the establishment. They have been to parliament, live on breakfast television and covered by the broadsheets. Next stop the High Court. It certainly has all the necessary ingredients of a potboiler.

At the height of the junior doctor stand-off, Jeremy Hunt disappeared from public view. Ben was one of many doctors, who manned the vigil outside the Department of Health. He was unexpectedly called in to an impromptu meeting with Hunt, one that lasted a whole hour. When he walked in to the building, he was surprised to find that the personnel already had a name badge prepared.

During the meeting, Hunt admitted that the NHS was under-resourced. But Ben found it difficult to get him to see an alternative perspective. I point out that the Government has not U-turned on the junior doctor contract despite the ferocious backlash. In fact, Theresa May has underlined continuity of policy by keeping Hunt in place.

I find this telling in light of other U-turns. My take is that this highlights the importance of opening up the NHS oyster to global capital. Ben adds that it would set a precedent for public sector pay restraint.

For Nadia, the political and the personal are inseparable. She takes me by surprise and opens up about the death of her older sister when she was very young. I can see that she is struggling to talk about it: “It never leaves you... you always carry it.”

Her sister was misdiagnosed and turned out to have a brain arteriovenous malformation. When it ruptured, she was taken to Great Ormond Street Hospital. Nadia now works at Great Ormond Street, which is evidently difficult. Her memories of this traumatic period are patchy but she still vividly remembers the day when her sister was taken off life support.

I can’t help but wonder if this is why she became a doctor. “Not consciously,” she tells me. Did she go into medicine to stop other families going through what they did? She was “the best big sister you could ever have”. Her youngest sister shares “many of the [same] characteristics... very loving and nurturing”. Nadia wanted to perpetuate these traits in herself and she agrees that this may partly explain her decision to study medicine.

* * *

On a balmy summer evening at the South Bank, I meet with Dr Francesca Silman. Francesca is pretty with mousey hair. She is a GP registrar and will soon be a fully-fledged GP. She strikes me as being prim and proper – exactly the kind of GP one would want.

Technically, she will not be a junior doctor for much longer. However, the contract dispute was never primarily about self-interest. We both agree that the framing of the narrative has focused too much on pay and conditions instead of privatisation. As a result, the message has not been clear enough that this is about patients and the public as much as it is about doctors.

She has seen the NHS provide life-saving treatment for several family members. Having also received life-saving treatment myself over the past year, we have plenty of common ground.

Francesca has an impressive academic background. She graduated from Oxford University, where she studied mathematical physics, human sciences and anthropology. She went on to study medicine at University College London. I’m told that Francesca and Marie-Estella are the PR machine of the operation – they are savvy with plenty of useful contacts.

The case revolves around hoisting the Government by its own petard. Francesca helps me to to get my head round the various intricate legal arguments.

The crux is that the Government’s Health & Social Care Act 2012 has abolished the National Health Service in legal terms. The act axes the responsibility of the Health Secretary for the NHS. It devolves this responsibility to various bodies, including the Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), and undermines the basis of these bodies to provide comprehensive care. It also opens up NHS contracts to potentially unlimited privatisation and enables foundation trust hospitals to earn up to half their income from private patients.

The case will pursue the ultra vires argument that the Government no longer has the legal powers to impose a contract on NHS staff. It is worth noting that some foundation trust hospitals have hinted that they may refuse the contract.

Yet this is a double-edged argument. If the High Court rules in favour of Justice for Health, could this mean the end of the national contract in the NHS? The group believe that the Government is scaremongering having consulted experts. Their case simply highlights the relevant issues.

They hope that the Judicial Review will spotlight for the public that the Health & Social Care Act has abolished the NHS in legal terms and, in turn, provide the momentum for the NHS Reinstatement Bill. This legislation would repeal the Health & Social Care Act and restore the NHS as a publicly provided, owned and accountable system. Jeremy Corbyn has recently announced Labour’s backing for the NHS Reinstatement Bill, a seismic step as it flies in the face of 30 years of NHS policy-making based on neoliberal marketisation and privatisation.

Whatever the outcome, Justice for Health should hopefully have its day in court. Are they confident? Ben remarks that, in public interest law, winning is important but the process is also key as it entails collecting available evidence, which leads to revelations.

I’ll try to keep this in mind as the case unfolds over what promises to be two days of high drama at the High Court.

How to Dismantle the NHS in 10 Easy Steps is published by Zero books – http://www.zero-books.net/books/how-dismantle-nhs-10-easy-steps

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments