The decision not to lift Jon Venables’ anonymity order shows judges will not give in to the internet

Analysis: James Bulger’s killers may evoke little sympathy but, as Will Gore explains, they remain vulnerable to being killed themselves if their new identities become widely known

It should really come as no surprise at all that the family court on Monday ruled against varying the injunction that prevents the new identity of Jon Venables from being made public.

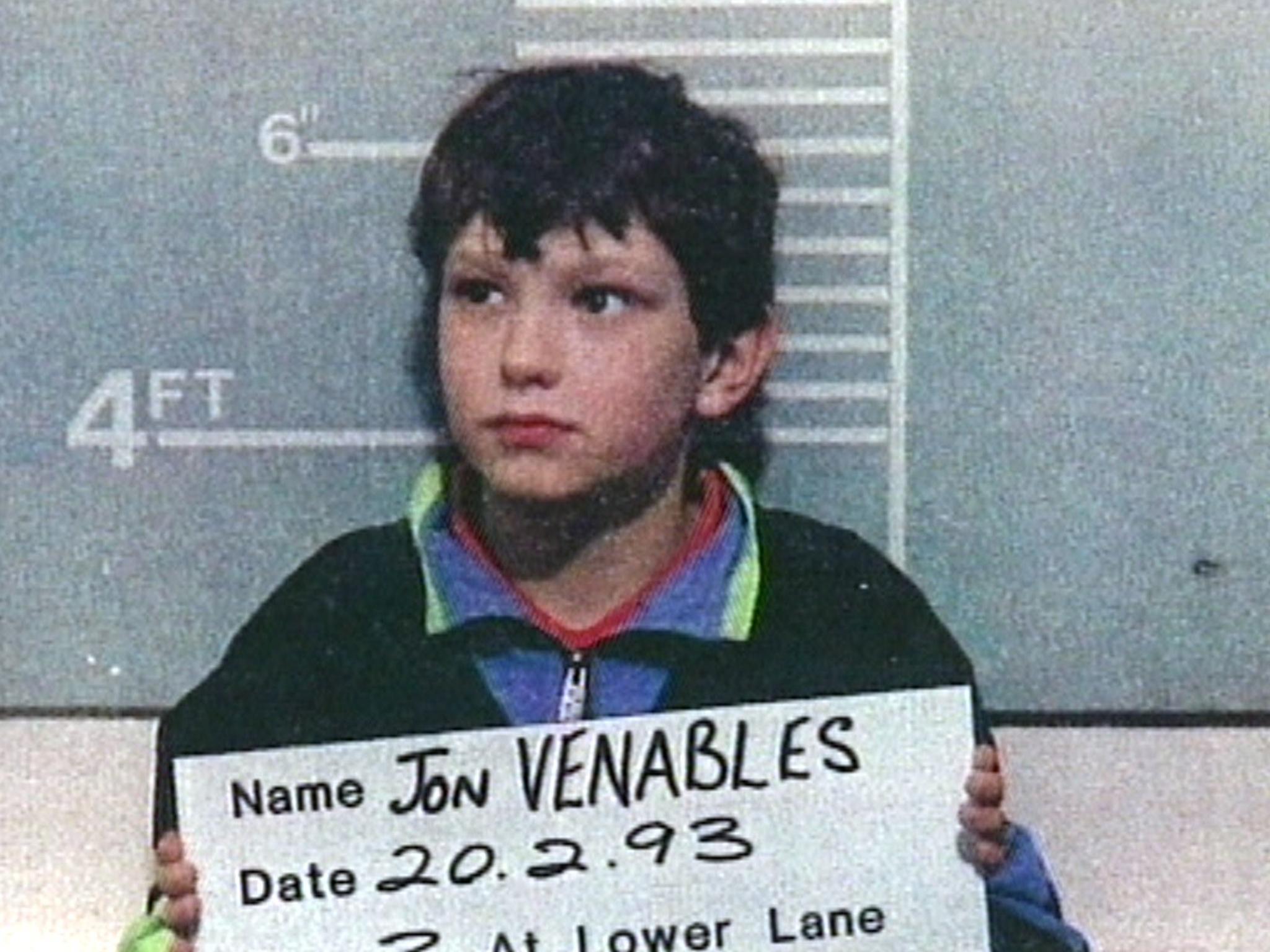

Venables was 10-years-old when he and Robert Thompson murdered the toddler James Bulger.

The sadistic killing in 1993 left the two-year-old’s family devastated and caused widespread revulsion, with Thompson and Venables becoming the youngest people to be convicted of murder in England in modern times.

The killers were sent to a young offenders’ institution, where they stayed until they were 18, receiving extensive rehabilitation along the way.

On their release in 2001, the boys were given new identities, protected by a lifelong anonymity order.

While Thompson has not re-offended, Venables has – convicted in 2010 and again last year in relation to making child abuse images and possessing a “paedophile manual”.

James Bulger’s father, Ralph, had sought to persuade the courts that the original anonymity order in respect of Venables was no longer sustainable, such was the extensive circulation of details regarding his new identity.

However, Sir Andrew McFarlane, the president of the family division, was not persuaded.

He noted that there remains “a strong possibility, if not a probability, that if [Venables’] identity were known he would be pursued, resulting in grave and possibly fatal consequences”. Given that the purpose of the 2001 order was to prevent Thompson and Venables from being “put to death”, the judge’s ruling is a slam dunk.

It was also inevitable.

There may be occasions when information is so widely known that maintaining a legal injunction makes little sense. But that is not the case here.

Moreover, the impact of Venables’ new identity becoming known is – as Sir Andrew made clear – potentially deadly. It is not equivalent to the revelation of a person’s love life (see Ryan Giggs), where the consequences of an injunction being breached are distressing but not fatal.

It is true to say that the internet has changed the game when it comes to preserving the sanctity of a court order. Such is the ease and speed with which information can spread, judges must occasionally feel like they are fighting a losing battle.

In the end though, that makes it all the more important that judges stand firm. If jurors think it’s OK to look up online details of the case they’re adjudicating on, and if people who wish Jon Venables harm can look up information about his new identity with impunity, the dam will be breached – and the integrity of our criminal justice could easily be washed away.

Sir Andrew was at pains in his judgment to underscore the point that his decision did not reflect on the applicants themselves (Ralph Bulger and his brother, Jimmy), “for whom there is a profoundest sympathy”.

Sure enough, the fact that Bulger is still wrapped up in legal processes 26 years after the appalling murder of his son, sadly serves to highlight how the tragedy visited on his family is never ending.