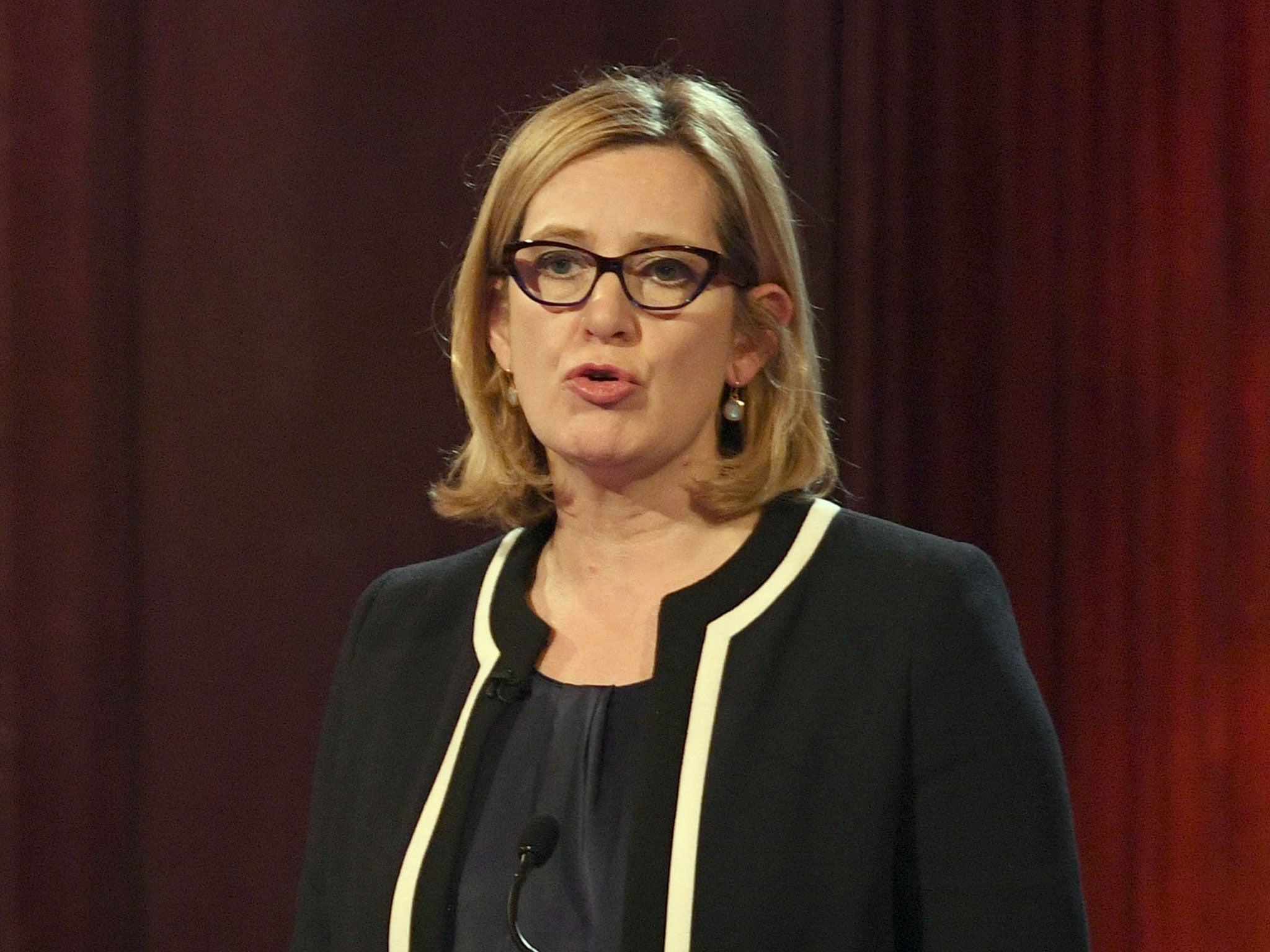

Amber Rudd's push for technology firms to tackle terror only deal with part of threat, experts warn

Analysts say targeting of specific sites and apps only deals with 'current way problem is manifesting itself'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.including Terror experts have warned that the British Government’s proposals to clamp down on extremists’ use of encrypted messaging apps and the internet could push them further underground and away from security services’ monitoring powers.

During a visit to the US to meet with technology giants including Facebook, Twitter, Microsoft and Google, the Home Secretary said there was a “problem” with the growth of end-to-end encryption.

Amber Rudd called on some of the world’s biggest online service providers to use artificial intelligence to prevent jihadi propaganda being posted, and hand over information including metadata to security services to help them trace and monitor suspects.

“They have to make sure that the material terrorists put up gets taken down or, even better, that it doesn’t get put up in the first place,” she told the BBC.

“A lot of the stuff that is getting up there shouldn’t get up there at all – none of this stuff should be online. They need to take ownership of making sure it isn’t.”

Isis has made prolific use of the internet to spread its propaganda around the world in multiple languages, switching from mainstream platforms like Twitter and Wordpress to rapidly shifting websites and encrypted messaging apps as a global crackdown intensifies.

WhatsApp became the target of public concern following the Westminster attack, when it was used by Khalid Masood to send a final message before ploughing his car into pedestrians and stabbing a police officer to death.

Intelligence agencies have since uncovered the content of the message, The Independent revealed, but concerns have risen about the difficulty of intercepting terrorists’ communications.

Jean-Marc Rickli, a research fellow at King's College London and the Geneva Centre for Security Policy, said targeting specific apps and providers was a “bit like whack-a-mole”.

“Since 2014 we had a lot of examples where Isis used platforms and moved to new ones,” he told The Independent.

“At one point they used WhatsApp, then Telegram and now new applications including the video games chat function…these groups are very quick at adapting.”

Dr Rickli said that while large technology firms may cooperate with the Government’s demands, smaller firms may seize upon the business model

“You can tell the big tech companies to do it but other companies will find a business model,” he added.

“If you imagine you are able to shut down all these websites and applications, they would still be able to communicate on the dark web and that would make things even more difficult for law enforcement.”

He also cautioned over the prospect of “censorship” by the pre-emptive blocking of posts, with Ms Rudd failing to detail who would decide what would be prohibited and how.

“It’s not a decision that will solve all the problems, and it could create more than it solves,” Dr Rickli added.

Ms Rudd acknowledged that online radicalisation was not the “whole story” in combating terrorism but added: “It is an important part of it and it’s a part we can do something about.”

Oz Alashe, the CEO and founder of CybSafe, said her proposals regarding pre-emptive blocking and the use of metadata from encrypted apps were both technically possible.

“Whether firms would the Government to access that data remains to be seen,” he added. “I think they would have a job persuading providers to do that willingly.”

Ms Rudd also said there was end-to-end encryption was a “problem for security services and police who are not, under the normal way, under properly warranted paths, able to access that information”.

“We are not asking to weaken encryption at all in terms of its existence now and the services we use, we’re just saying that the organisations that have end-to-end encryption work with us to share certain elements,” she added.

“Like for instance on metadata, they could do much more so that we could use that information to keep people safe.”

Mr Alashe, a former lieutenant colonel in the UK special forces, said data showing what phone numbers were communicating with each other, when and for how long could be instrumental in terror and criminal investigations.

“The reality is that terrorist groups and organised criminals will find other ways to communicate if the ways in which they currently communicate are unavailable to them,” he added.

“That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t make them unavailable, it just doesn’t mean they will eradicate the issue.

“You’re not dealing with the problem, you’re dealing with the current way it’s manifesting itself.“

David Videcette, former counter-terrorism detective in the Metropolitan Police, said metadata would be a useful tool for investigators, as is any move to block online propaganda.

“We don’t want to go back to 2013 when Isis had free reign to do what they wanted and were recruiting people left right and centre, making Syria out to be some fantasy utopia,” he told The Independent.

Mr Videcette, who has written several books based on his experiences investigating the 7/7 bombings and other plots, said there was a “balance” between people’s right to privacy and the needs of security services.

He said something had “obviously gone wrong” in the cases of Manchester attacker Salman Abedi, London Bridge ringleader Khuram Butt and other terrorists who had been known to British authorities but not judged to be an imminent threat.

“Those people were on the radar and the risk assessment didn’t have all of the right information to come up to standard,” he added.

“Those things happen because we don’t know who is talking to who and when…if we had they might have changed the risk assessment and been able to arrest them and save lives.”

Mr Videcette stressed the importance of being able to investigate the wider network of contacts, radicalisers and coaches surrounding terrorists.

“They’re not lone wolves, lone wolves don’t exist and it’s imperative we can investigate and if this data isn’t there we can’t,” he added.

“We need judicial oversight on [intercepting communications] on an individual basis. It shouldn’t be allowed at will.”