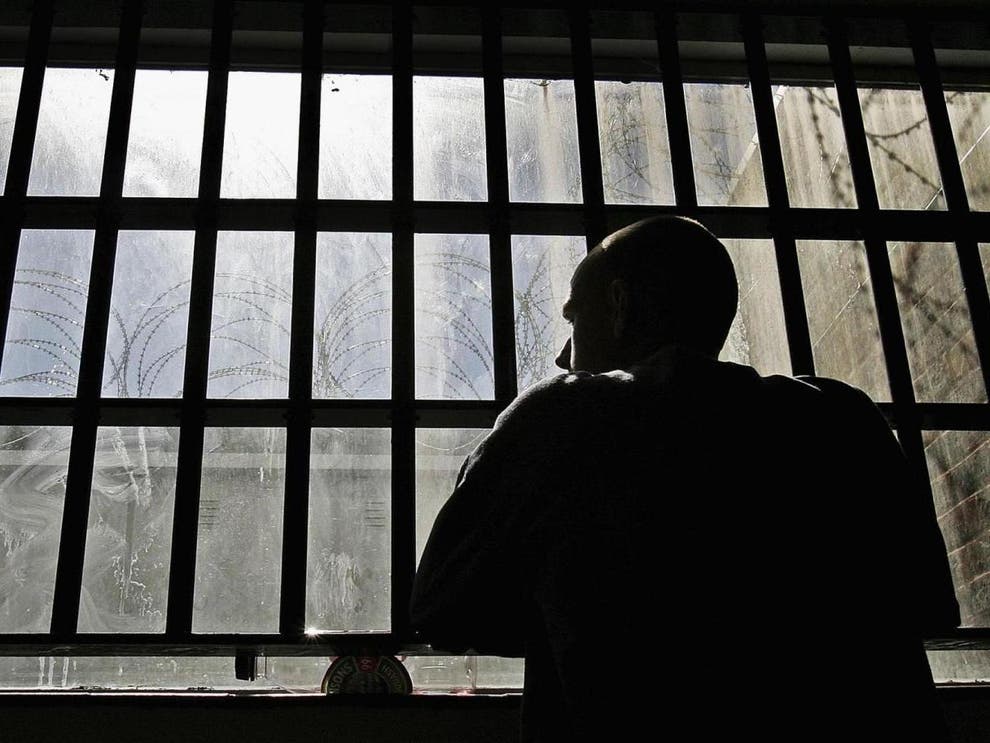

‘It’s psychological torture’: Immigration detainees tell of being locked up for up to 24 hours a day during pandemic

Men held under immigration powers in jails reveal the dark realities of Covid restrictions in prisons – and how the indefinite nature of their detention exacerbates the torment of spending whole days in a small cell, May Bulman reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“The days and nights blur together. I can barely sleep at night but when I do, I experience nightmares. I feel like I’m being stripped of my identity, that my personality is being broken down. It’s psychological torture.”

Richard*, 23, speaks from a prison cell he has been locked in for more than 22 hours a day since March 2020. Some days he has only stepped out of the small, stuffy room for a mere 30 minutes.

The Portuguese national, who has lived in the UK since he was six, is not doing time for a crime. He served a jail sentence for drug offences, but that came to an end in February 2021. Now he is detained purely based on the fact that he isn’t British.

He is one of around 570 immigration detainees currently held in prisons in the UK – a 70 per cent increase compared to March 2019.

Non-British nationals who are sentenced to jail for longer than 12 months in the UK, such as Richard, are liable to be deported, and can be detained under immigration powers at the end of their custodial sentence pending their removal from the country, which could be at any time.

They are usually transferred to an immigration removal centre, where conditions are less restrictive and they have better access to legal advice.

However, since the start of the pandemic, the Home Office has sought to hold fewer people in removal centres for Covid-19 safety reasons, placing many in prisons instead.

At the same time, restrictions in jails have been severely tightened. Since March 2020, inmates have been held in their cells for 22 to 24 hours a day to contain the spread of Covid-19.

When you’re doing a sentence you know your release date, but when you’re detained it can be two days, a year, or never

A new report from the Bail for Immigration Detainees (BID) and charity Medical Justice, seen by The Independent, raises concerns that these conditions and lengths of isolation amount to prolonged solitary confinement, which may amount to a breach of inmates’ human rights.

The findings, based on interviews with detainees and casework, show that such conditions can exacerbate existing mental health conditions and precipitate the onset of new ones – made worse by a “concerning” lack of medical support available to people confined in prisons.

While this applies to all prisoners, the report states that solitary confinement is particularly damaging for those detained under immigration powers, as their imprisonment has no end date, “exacerbating feelings of helplessness, in comparison to finite sentences”.

Richard – who before entering prison at the end of 2018 already suffered from depression and PTSD stemming from a past experience of torture – now suffers from nightmares and flashbacks, and is reliant on medication.

His testimony from inside jail was featured in the report. Now, having been released on bail in May, he tells The Independent he still feels traumatised by the long periods of time he was locked up alone in his cell.

The young man, who is now trying to fight his case to remain in the UK, where all of his family are settled, says that while in jail he was stripped of his identity and that his personality was slowly “broken down”, to the point where he is now struggling to integrate back into normal life.

“In prison, I started feeling nervous to go outside, to the point where I wouldn’t take my daily exercise. I didn’t like the sunlight so I had my curtains down in [my] cell. It’s like my brain was tormenting me,” he says.

“The first days being out of prison, I didn’t know what to do with myself. There was so much I wanted to do, but I couldn’t. I’m still not back to normal. Doing basic things like going to the shop or sitting on a train doesn’t feel right.”

The 23-year-old says that being in jail became dramatically more difficult when he came to the end of his sentence and was detained under immigration powers.

“It suddenly became much harder because of all the unknowns. When you’re doing a sentence you know your release date, but when you’re detained it can be two days, a year, or never, and they might come and put you on a plane at any point. It was awful,” he adds.

Another immigration detainee, Omar, has been held under immigration powers since his jail sentence for robbery ended in October 2020. This is despite the fact that he agreed to return to his home country in January 2020.

He tells the report’s researchers that being locked alone in his cell for between 23 and 24 hours a day – sometimes not able to leave it at all, preventing him from showering and exercising – had a profound impact on his mental health, driving him to have suicidal thoughts.

“Every day is like torture. I feel suffocated and feel like I want to hurt myself or end my life because there is no other escape,” says the 47-year-old.

“I wake up in the middle of the night, struggling to breathe. My body starts to shake by itself and I feel like I’m going to die.

“I didn’t go into prison with any mental health problems but now I experience anxiety, very low mood, panic attacks and insomnia.”

I honestly don’t understand why the government is spending money on keeping me in prison

Omar was released on bail this week. Speaking to The Independent days later, still in the UK and living in a shared house he was placed in by the Home Office, he says was having panic attacks every night and felt fearful of going outside.

“I feel scared, I don’t know why. I was very healthy, but now I feel like I’m lonely and feeling down all the time,” he says.

Omar says he was shocked that the Home Office kept him in prison for 17 months after he had agreed to return to his home country.

“Initially it was because of Covid, but there has been a lot of time now when I could have flown back to my country. I honestly don’t understand why the government is spending money on keeping me in prison. It must be costing the taxpayer so much and it’s completely unnecessary.”

Annie Viswanathan, director at BID, says: "I hope this report causes the people with the power to take stock and reflect on the continuing use of a barbaric practice that shames our society.

“This cruelty needs to end and people should be released so that they can be supported in the community.”

Emma Ginn, director at Medical Justice, echoed her remarks, saying the charity’s clinicians had witnessed first-hand the “devastating” effect solitary confinement has on immigration detainees, describing the practice as “profoundly disturbing”.

“That this imprisonment extends beyond a criminal sentence means severe harm is being inflicted during, and because of, a period of entirely unnecessary and purely administrative detention – we need to question if this is civilised or in fact gratuitous,” she adds.

“It is certainly the biggest scandal most people have never heard of.”

A government spokesperson says it took the welfare of detained individuals in its care “very seriously” and that some individuals had been placed in prisons rather than immigration removal centres to prevent the spread of Covid in those centres.

They add: “We are responding to the unique circumstances of the Covid-19 outbreak and the decisive action we have taken during the pandemic, backed by Public Health England, has meant thousands of immigration detainees, officers and prisoners have been kept safe.”

*Not his real name.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments