Human trafficking: How a charity is rescuing the victims the authorities knew nothing about

The work of Hope for Justice highlights a gap in law enforcement for one of Britain’s most hidden crimes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The stocky middle-aged Polish man was sweating nervously when he turned up at the soup kitchen in Birmingham with no possessions and no English to articulate his distress.

Workers at the homeless centre initially suspected mental illness. With the aid of a translator and a series of one-word answers, the man finally revealed that he had been brought to Britain, housed, and put to work by Polish Roma. Staff suspected human trafficking and called in the experts.

But they did not turn to the police to investigate a potential international crime, one that the Home Secretary Theresa May has declared a top priority for law enforcement. Police have stopped their once regular visits to the centre, Sifa Fireside, according to the officials.

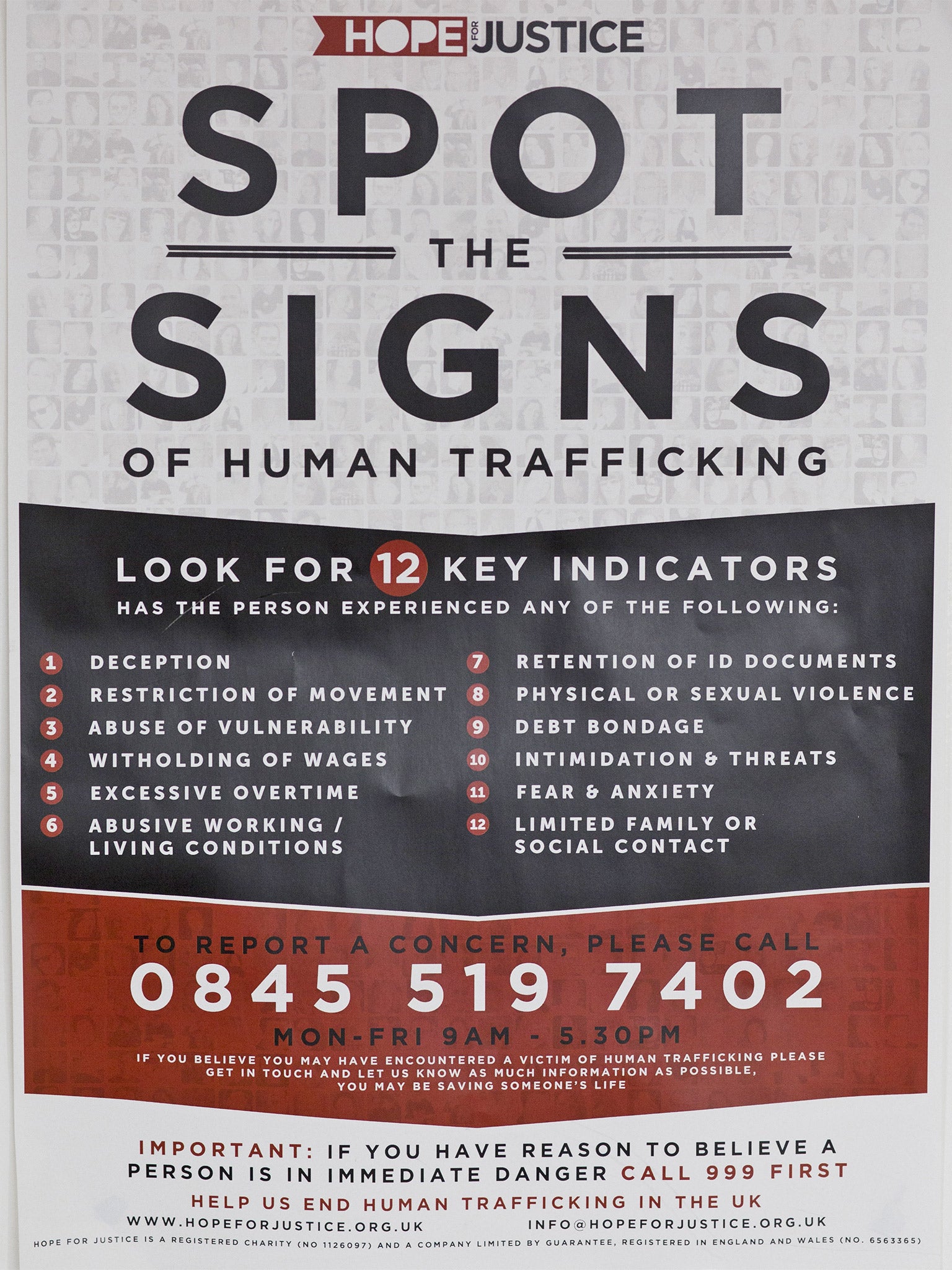

Instead they called a Christian charity, Hope for Justice, which supplied the training and the posters on the wall detailing the 12 tell-tale signs on how to spot victims of trafficking. With its small team of six investigators, the West Midlands branch of Hope for Justice has rescued 82 people so far this year. Many of those were unknown to police, highlighting a gap in law enforcement for one of Britain’s most hidden crimes.

Fewer than 10 of the 43 forces in England and Wales have specialist anti-trafficking teams, says Kevin Hyland, the Government’s anti-slavery commissioner, and few cases of modern slavery have gone through the criminal justice system. Only 130 cases that involved human trafficking were successfully prosecuted in 2014-15, representing just one prosecution for every 100 potential victims, according to Home Office statistics. Mr Hyland, a former policeman, argues that conviction rates must increase. Charities, such as Hope for Justice, appear to be partially filling the gap.

The charity – which also operates in Cambodia, the US and Norway – is thought be unique in the number of ex-officers it employs to carry out inquiries. They do not have the powers of search, arrest and intrusive surveillance, so prosecutions rely on working with the police. Investigators for the charity in the north of England helped to secure convictions last year in cases where people were living in cramped conditions while being forced to work long hours for very low pay.

In the West Midlands – the charity’s second and newest operations centre – investigators at the charity say that since the start of the year they have dealt with people forced into crime, domestic servitude and the sex trade, and in one case, a man who claimed to have been a targeted by traffickers for his organs after being drugged and forced to paint himself in iodine before fleeing from a bathroom window. Police – who interviewed the man – doubt his story, but Hope for Justice staff say his claim to be trafficked is currently being assessed.

The staff in the West Midlands operate from a nondescript, unmarked office. The bulk of their work is responding to calls for help from soup kitchens and food banks where they have trained staff. The former police officers now working for the charity – whose specialisms include undercover policing and financial investigations –have conducted surveillance work, including on girls working at a nail bar that they suspected of being victims of trafficking.

On getting the message from the soup kitchen about the mysterious Polish man, the charity sent a former undercover officer, Richard, and his Polish colleague Piotr. While dozens of homeless men ate curry and rice, the pair took the man into one of the small private consultation rooms to try to unravel what has happened to him. After 30 minutes of mistrust and fear, he finally spilled out his story.

The man told them that he had been approached by Polish Roma in April in his home city of Poznan who offered him work in Britain for £250 a week. He had just been made homeless, and was mourning the recent death of his mother, so he jumped at the chance. According to his account, he was put on the 44-hour bus trip to Birmingham with a fellow Pole where he was collected by a member of the gang. He was taken to a squat in a disused factory with no heating and a mattress on the floor.

For three weeks he did not work, but one of the traffickers helped him to open four bank accounts, he told Richard and Piotr. Eventually, he was put to work at a factory in Worcestershire, taken there by his trafficker and brought back again. He was given £50 a week in cash.

Working at the factory he broke his arm, but traffickers refused to take him to hospital, and he fled with the arm healing without any medical attention. Homeless again, he was picked up by unrelated Polish Roma from the city centre and offered a job in landscape gardening and was paid a fifth of what he was promised. When he challenged his wage, he was threatened and he fled back to the streets.

For Richard, it was a familiar story. The modus operandi suggested that he had been targeted by one of two main organised criminal gangs identified by the investigators as operating in the West Midlands. Criminals view the trade as high-profit combined with a low risk of getting caught. A minibus of vulnerable trafficked men forced into labour represents £10,000-£15,000 a month to the traffickers.

The police will say: anyone here who has been trafficked? The soldier will say: of course not, we’re all working, it’s fine, no problem at all

The technique of one of the Polish Roma groups is to approach vulnerable men at railway stations in their homeland, recruit them and bring them to Britain. The criminal leaders keep their distance and activities are usually controlled by a “soldier” – another victim of trafficking – but who becomes trusted, and acts as the eyes and ears of the gang. He collects documents and, with a grasp of English, deals with the police.

“We’ve had cases where we have had victims who were present at an address where there was police intervention,” said Kevin, another ex-officer working for the charity. “The police will say: anyone here who has been trafficked? The soldier will say: of course not, we’re all working, it’s fine, no problem at all. The police have withdrawn and the traffickers will then move all the victims to another address.”

They have learnt of cases where a person has dressed up as a policeman and assaulted one of the trafficked men to emphasise their vulnerability, and where a cat has been drowned in front of them. The implication is clear: do as we say, or you’re next. “It’s mental rather than physical control,” said Kevin.

While the Polish man recounted his story, he was physically shaking and sweating, said Richard. “He was constantly looking outside the door,” he said. “The traffickers were chasing him on the streets this Monday, but he managed to get away.”

The investigators took him in their car to identify the places where he was taken. He pointed out the squat at the factory, which appeared to be under renovation and being turned into flats.

130

Cases that involved human trafficking were successfully prosecuted in 2014-15

Despite his providing details of landmarks – a supermarket and a swimming pool – they were not able to find the house where the main trafficker lived. Richard will feed the information back to the West Midlands Police which is investigating the gang based on the victims that the charity has found.

The Polish man was found somewhere to stay for the night. Hope for Justice arranged for him to meet police the following morning to give a statement about his plight. They later discover that he did not go. Investigators said that less than 10 per cent of people go the police, a fact played on by the traffickers. That increases to nearly 90 per cent once they are in the national referral mechanism (NRM), the network of safe houses that provide a haven for up to 45 days.

“We used to get people drive by, stop and ask our clients if anybody wanted some work,” said Mary Mantom, facilities manager at Sifa Fireside.

“The vulnerable adult has always been a target market for the people that want to exploit them.” She said a police team used to come in regularly and speak to the men to find out what was happening on the ground. “That’s stopped now, we’re not getting any police presence. I think their structure has changed or their priorities have changed. I suppose Hope for Justice is meeting our requirements.”

West Midlands Police, which referred only 37 people to the NRM in 2014, says it works closely with the charity to provide intelligence from people wary of going to the police. It does not have a dedicated trafficking team, though it has ramped up its efforts and was in line to treble that number this year.

Detective Chief Inspector Tom Chisholm, who heads West Midlands’ anti-trafficking efforts, said the force had got better at spotting the signs of trafficking and the number of people referred had increased sharply. “In the past, reports of groups of Eastern European men coming and going from a property may have been wrongly labelled as an anti-social behaviour issue when, in reality, trafficking could be the root problem.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments