How Britain considered transplanting population of Hong Kong to new 'city state' in Northern Ireland during height of Troubles

Proposals in 1983 suggested a chunk of Ulster - between Coleraine and Londonderry - be turned into a new home for Hong Kong’s 5.5m citizens

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.British officials considered transplanting the population of Hong Kong to a new “city state” in Northern Ireland at the height of the Troubles under a plan to deal with the end of Britain’s lease on its Far East colony.

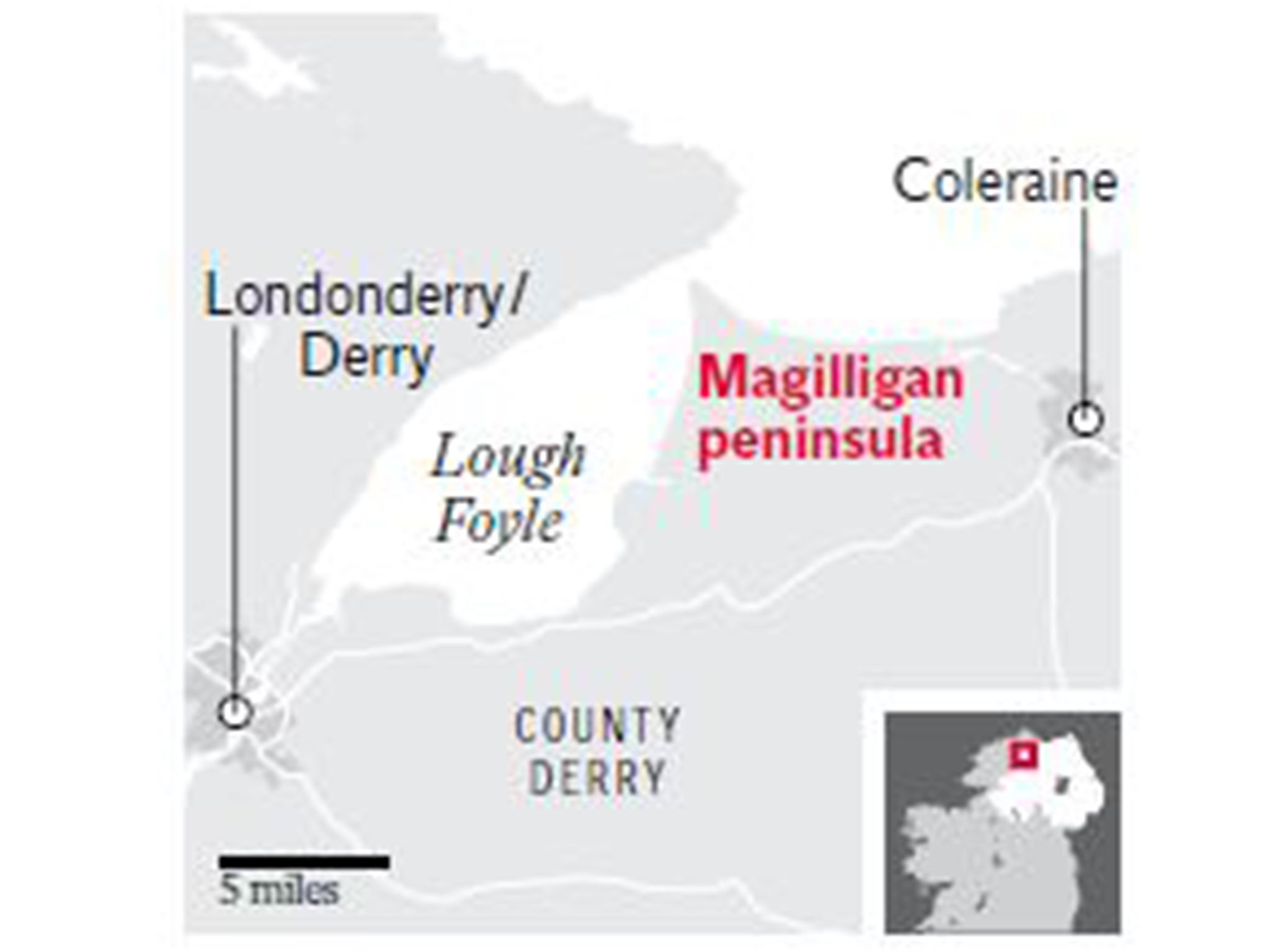

Newly-declassified documents released at the National Archives in Kew, west London reveal how senior civil servants reacted enthusiastically to proposals in 1983 from a University of Reading academic that a chunk of Ulster - between Coleraine and Londonderry - be turned into a new home for Hong Kong’s 5.5m citizens.

The proponents of the plan, which one Northern Ireland office official declared should be “taken seriously”, suggested the mass transportation of Cantonese speakers would have the dual advantage of boosting the Ulster economy while solving Britain’s dilemma over what to do with the millions of Hong Kong residents concerned they would have no future under Chinese rule.

The plans were laid out as London was in the depths of ongoing negotiations with Beijing over the future of Hong Kong as Britain’s 99-year lease on a large part of the territory was due to expire in 1998.

Britain eventually struck a deal a year later with the Chinese declaring Hong Kong as an autonomous “special administrative region” and including supposed safeguards for democracy in the territory.

But the previously unseen Foreign Office documents, which appear to be closer to a lost script from Yes Minister! than the sober machinations of the Civil Service, suggest that Britain was prepared to discuss even the most outlandish proposals to discharge its responsibilities to Hong Kong’s Cantonese residents.

When details of the scheme, floated by sociology professor Christie Davies, appeared in a Belfast newspaper in October 1983, they caught the eye of George Fergusson, an official in the Northern Ireland office.

A memo fired off from Mr Fergusson to the Foreign Office suggested that the mass arrival of Hong Kong natives in a newly-declared territory on a sparsely-populated peninsula outside Londonderry would have the advantage of reassuring Unionists of the “open-ended nature of the Union”.

The document goes on to suggest that Brussels could have few objections to the “plantation” of a new population, noting that a “pilot scheme” which had seen 50 Chinese-Vietnamese families settled in Craigavon had “at least established that the Chinese do not find the Northern Ireland climate objectionable and they can get on reasonably well with the current inhabitants”.

The memo asks whether officials should be preparing to find the same number of square miles of territory occupied by Hong Kong or looking for “an area of the same shape”.

In a final flourish, it suggests that while negotiations take place across Whitehall, functionaries could start taking “precautionary measures” to ensure the likely site for the New Hong Kong is kept free of problematic planning applications.

It added: “At this stage we see real advantages in taking the proposal seriously.”

Unfortunately, the earnestness of the Northern Ireland Office does not seem to have been reciprocated further along Whitehall.

With his tongue firmly in his cheek, David Snoxell, a diplomat in the FCO’s Republic of Ireland department, expressed concern that the arrival of 5.5m Cantonese in the Londonderry hinterland might provoke a large-scale departure of the native population in the opposite direction towards Hong Kong.

The official wrote: “We should not underestimate the danger of this taking the form of a mass exodus of boat refugees in the direction of South East Asia.”

He continued: “On the other hand, the countries of that region may view with equanimity the prospect of receiving a God-fearing, law-abiding people with an ingrained work ethic, to replace those that have left. Arrangements would, of course, have to be made for them to retain their UK nationality.”

The retort seems to have met with approval from other diplomats. One note in the margins reads simply: “Lovely!”

Prof Davies said he never received a formal approach from the Government to discuss his proposals - but hinted to The Independent that his idea may not have been entirely serious in the first place.

The academic, who has subsequently specialised in studying the nature of comedy, said: “I am glad my sensible idea was taken seriously. It was humorous but deliberately ambiguous. My test of a good humorous satire is if a significant minority take it seriously.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments