Historic hunting ponds uncovered in Kent marshes

Historic England announces discovery of a remarkably well-preserved example of this 400-year-old harvesting technique

For the 17th-century landowner who had everything it was the ultimate accessory for the new culinary craze for wild game - a decoy duck pond to harvest one’s waterfowl.

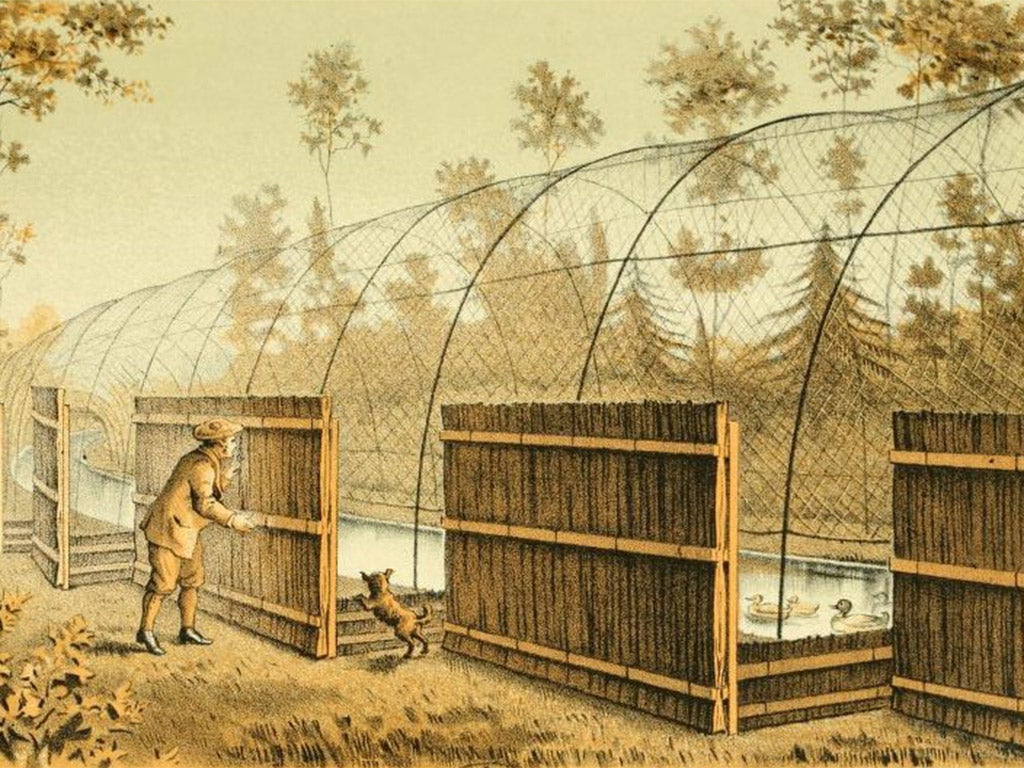

Some 200 of these starfish-shaped structures, consisting of a large pond with curving off-shoot channels down which hapless birds were funnelled into netted enclosures, once dotted eastern England to feed the gentry’s growing appetite for duck and other prey.

Most have long since disappeared but Historic England has announced the discovery of a remarkably well-preserved example of this 400-year-old harvesting technique on a windswept marshland in Kent barely 30 miles from London.

The wildfowl trap, which dates from at least 1698, is one of a number of sites on the Hoo Peninsula which are today given the protection of listed status following a survey of the area by the conservation body, formerly known as English Heritage.

The duck-trap pond at Halstow Marshes, near Gillingham, was one of dozens built across East Anglia from the early 1600s onwards after the idea was exported across the North Sea from the Netherlands - and in so doing gave the English language the word “decoy”.

The idea of trapping birds by driving them towards netting had existed in Britain since medieval times but the Dutch technique represented a significant refinement by covering a number of spur “pipes” to form curved, narrowing tunnels. Dogs were then used to startle the birds down the channel to a point where they could be caught and killed.

The Dutch word “eendenkooi” or duck cage was shortened and anglicised to become the English word “decoy”.

Ed Carpenter, who conducted the survey of the site for Historic England, said: “The Halstow Marshes pond is very well preserved, quite possibly because of the remoteness of the Hoo Peninsula itself. These ponds were brought into existence because the aristocracy wanted to have wild ducks on the dinner table but they soon became more commercial - some of the larger ones were catching up to 2,000 birds per season.”

The pond, one of just a handful that still survive in Britain, is not the sole example of the art of subterfuge discovered on the peninsula jutting out between the Thames and the Medway.

The study also found evidence of a decoy of an altogether different variety in the shape of a false oil installation designed to fool the Luftwaffe in the Second World War.

The bombing decoy site at Allhallows was part of a national network of hoax installations, from dummy airfields to whole towns, built with the aim of drawing Nazi aircraft away from genuine targets.

Researchers found the remains of the decoy site some three kilometres from a large complex of 100 genuine oil storage tanks on the Isle of Grain, used to fuel the Royal Navy.

Built by the Petroleum Board in 1941, the newly-listed dummy terminal consisted of five clay structures which were filled with oil and woodchippings to be set ablaze during attacks to trick pilots into believing that they were above their intended target.

Historic England said the findings showed that life on the once-boggy peninsula was far richer than many have assumed.

Sarah Newsome, a senior investigator for the organisation, said: “These historic sites represent so many aspects of human activity, from putting food on the table to the preservation of life itself during the Second World War. Through this project, we have revealed that the Hoo Peninsula has a complex history that goes beyond the familiar Dickensian idea of a low-lying land of misty marshes.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks