Hillsborough disaster: The story of Arthur Horrocks, one of the 96 victims

"It was when the stadium first came into view, at 2.30pm, that something seemed different and not quite right"

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

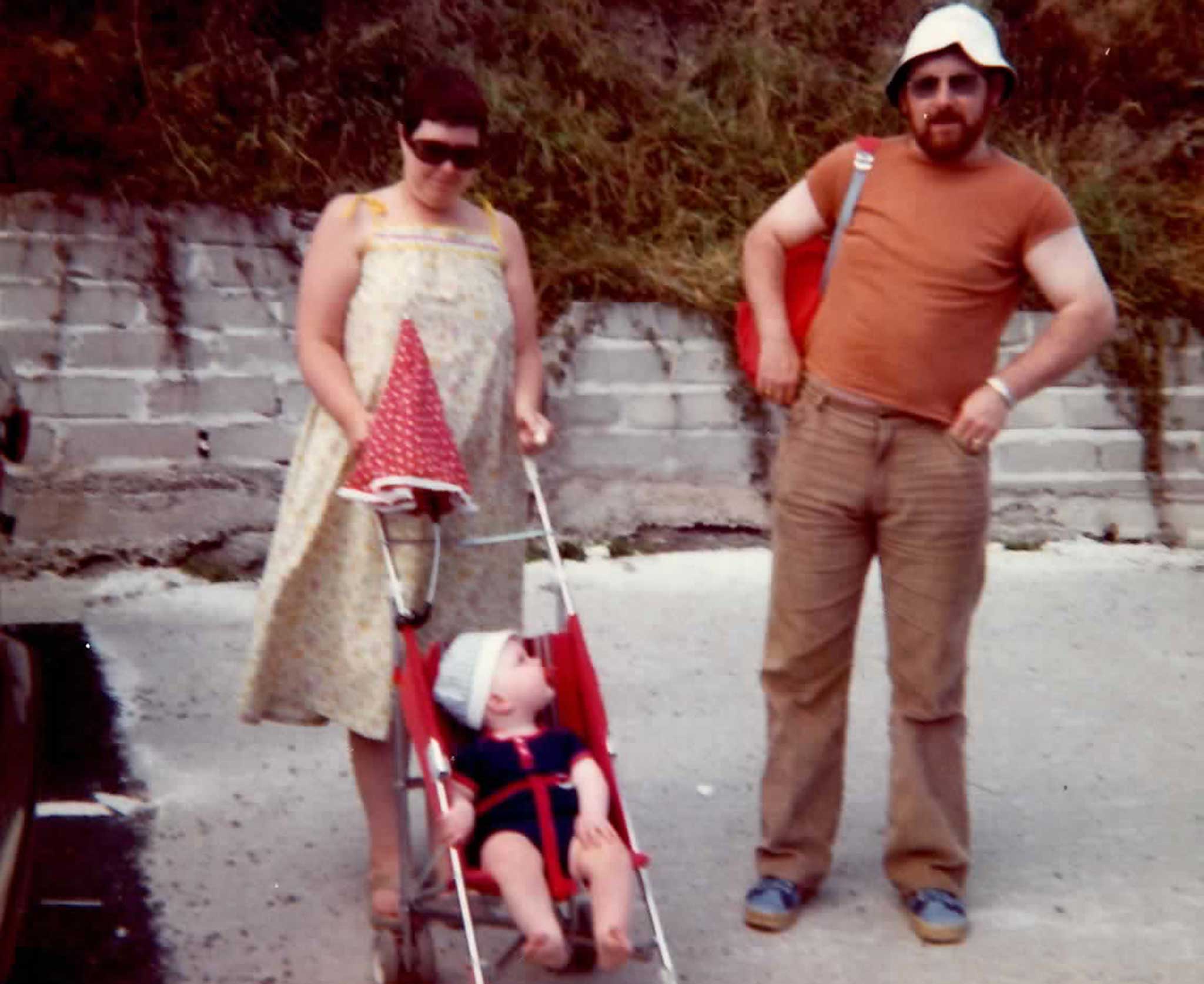

Your support makes all the difference.Arthur Horrocks was not the kind to shout about it, but he could reflect that he was making strides in the world on the warm Saturday morning in April 1989 when he packed up his yellow Triumph Toledo and set off for a day of football, leaving behind his wife, their young sons, and their home in middle class suburbia.

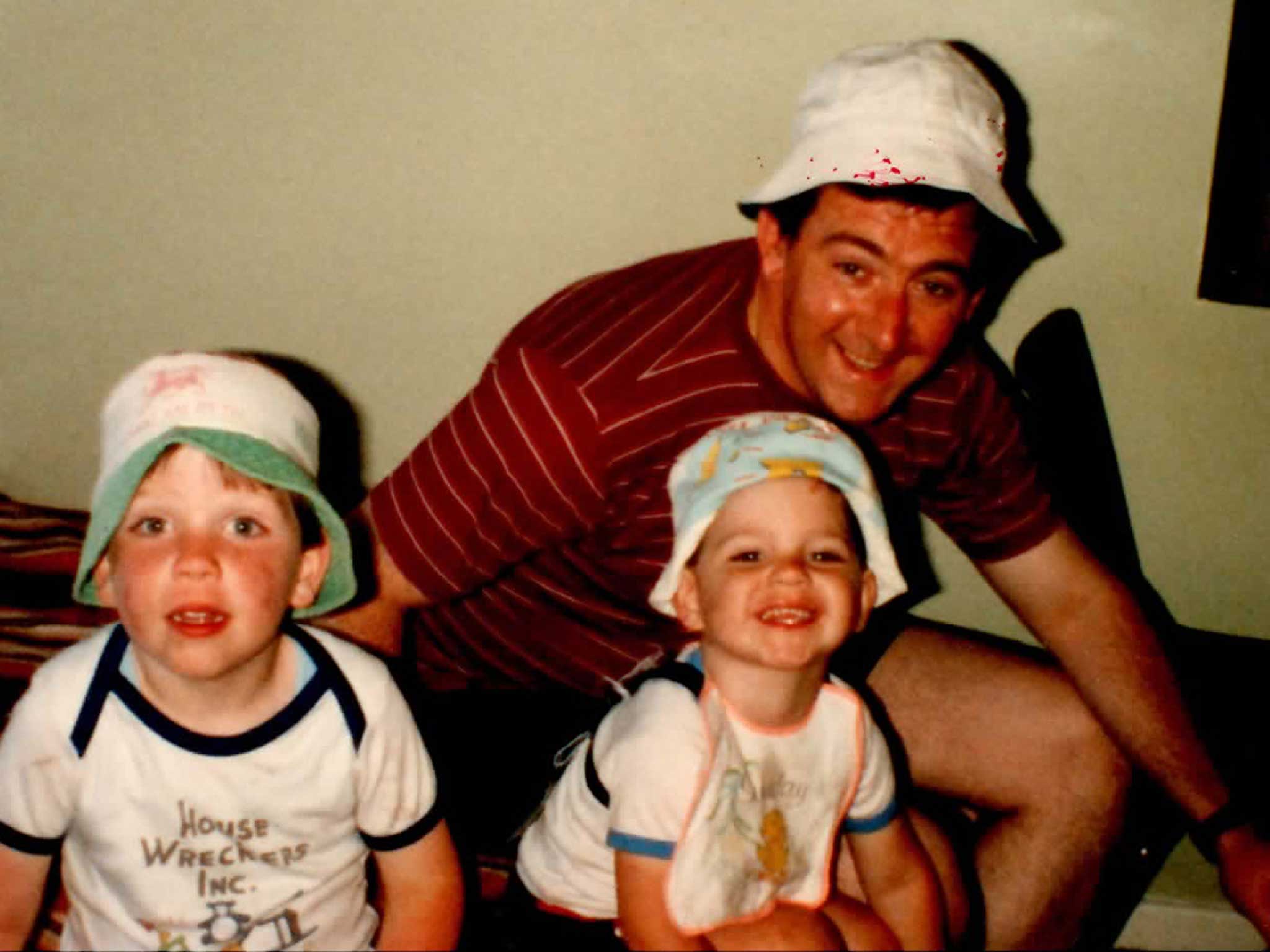

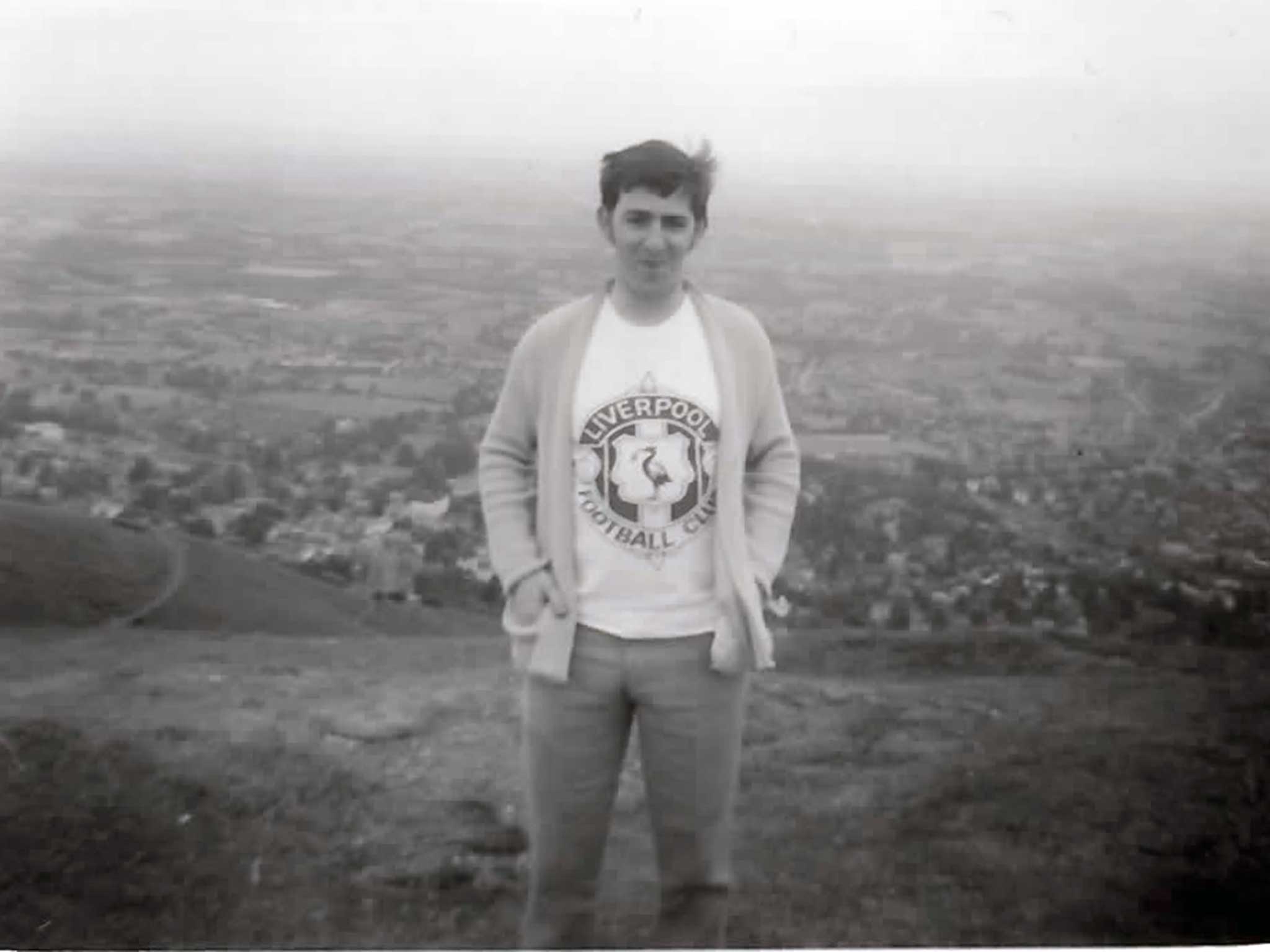

The car was as much the 41-year-old’s pride and joy as the redbrick house – Town Lane, Bebington, Wirral – for which he and Susan had moved out of Liverpool to settle and bring up their children - Jamie and Jon, aged eight and six on the morning he left. The comforts had not come easy. Arthur had swapped the familiar working routine of a life on the Liverpool Corporation buses – the same job he’d watched his brothers do, with plentiful overtime accruing – for a career selling insurance and pensions for the Prudential. He’d already been the ‘man from the Pru’ for about 10 years on the day he set off for Hillsborough. Intimate and companionable though that role in life might sound, he’d always worried that he was not “a salesman”, as he once told his nephew, Dave Golding, who, because a mere 10 years separated them in age, became one of his closest friends. “How can you ask for money from people who haven’t got it?” he asked Golding.

The rounds he undertook to collect his customers’ weekly cash payments – no standing orders and bank accounts for many of them – attested to the challenges. He was beaten up and robbed one night at the Sir Thomas White Gardens flats. It knocked his confidence and left him asking Golding to accompany him on his next round. He would see those who couldn’t pay hastily draw their net curtains when he approached and not answer his knock at the door. A woman in her 80s had offered him her poodle as a payment in kind on one occasion and, because she was struggling to handle it anyway, he accepted. The dog, Pip, was lively but it became a part of their lives. “Typical of Arthur to have been willing to take it,” says Golding.

They gathered early that Saturday morning as they often did before the Liverpool. Golding’s brother, Keith, was providing the transport to Sheffield with his works Transit van. Six of them piled in - Horrocks, his brother Malcolm, the Golding brothers, Keith Golding’s girlfriend Nicola and Dave Golding’s friend Alan Pybis. They were over the Pennine Woodhead Pass - which connects England’s North West with Sheffield – by 11.45am; early enough to spot a place for lunch at The Pheasant, at Oughtibridge village five miles outside Sheffield.

Horrocks passed on lunch, despite his companions’ encouragement to join them. The bacon sandwich Susan had made him, enjoyed on the way in the van, was enough, he’d insisted. They’d parked up outside the Oughtibridge Kitchens showroom and the publican told him they should leave the van there and catch a bus from the top of the road. It was a five minute drop into the city. They couldn’t believe their good fortune.

It was when the stadium first came into view, at 2.30pm, that something seemed different and not quite right. Golding had been here the previous year, when Liverpool had also played Nottingham Forest in the semi-final, and though there’d been crowds at the same time on that occasion, it had been orderly. This time a disorganised mass of people lay before them. They edged around to the flank of the crowd, inching forward until, against much expectation, they were through the turnstiles and inside Hillsborough before kick-off. They briefly separated to use the toilets and then ventured down under the dominant sign above a tunnel - ‘Standing’ – which pointed them to the terrace.

Briefly, it seemed like the usual football routine. The tunnel they inched through felt uncomfortably full but they made it out on onto the terrace and headed diagonally down to the front of what they would later know as Pen 3. Malcolm Golding said something in the tunnel about a “gate opening” behind them but they weaved their way between the gathering groups. They were about half way down the sloping terrace when they found they could get no further. At first they were being cast around on the swell of the crowd - “Left, right, down, back…” as Golding remembers it. Then all lateral movement stopped.

It was a desperate kind of paralysis. They were stationary, with an incremental tightening of the space and a growing sense of helplessness. Golding was able to shout an instruction to his brother and to Nicola. “Keep your arms up.” He thinks it was probably Nicola who began to feel the crushing first. His fragments of memory include the changing colour of her face, reddening in her mounting crush and escalating panic. Arthur was the main concern, though. He didn’t seem to be responding and he seemed to be motionless. “My brother could see him better than me,” says Golding. “From where he was, he could look back and see him and talk to him. But to me it looked like he had just fallen asleep. He was standing up, his eyes were shut…”

They’d been in this suspended horror for perhaps five endless minutes when a crash barrier, a foot in front of them, sheared off under the pressure. The landscape suddenly changed. People were plunged forwards. Others were being hauled out of the terrace behind the Horrocks group, and as the spaces opened up Golding fell between people into one, cracking his head on the concrete terrace. He lost his training shoes, which were squeezed from his feet in the melee. It was as he staggered to his feet, concerned about being submerged and with his ankles already trampled, that he saw Horrocks had fallen too – and was half-buried within a heap of bodies which had accumulated in that section of terrace.

He made for him and, with two supporters, lifted him up over the radial 6ft fence which divided their pen from a freer adjacent one. There was no time to try to speak to him in the pandemonium and in that instant, with the enormity of all this not dawning, it did not strike Golding that the older man was limp and unreactive. “I thought he’d fainted in the heat,” he says.

Golding had been helped out onto the pitch himself and ushered by a policewoman into a van which had doubled as a TV outside broadcast vehicle when he saw his uncle again - immediately identifiable by the arm of his distinctive leather jacket, hanging from a St John’s Ambulance collapsible trolley being wheeled across the edge of the pitch. He made to stand up and head for him, though the policewoman told him Horrocks was in safe hands and would be fine. She drew the curtains across the van’s front window.

Horrocks was placed at the side of the pitch where an ambulance crew, with their own trolley, collected him. That much was unknown to Golding who, taking the policewoman’s words at face value, was driven by ambulance to the city’s Royal Hallamshire Hospital and treated for a suspected broken ankle. There, on one of the afternoon’s countless random encounters, he saw his brother Keith and Nicola in the corridor. It was when Golding received his brother’s desperate and uncontrollable response to the question: “Where’s Arthur?” that reality struck. Perhaps traumatised, shutting out the events which have defined all of their lives, Malcolm Horrocks has never been able to discuss what happened, across the course of 27 years.

The events of the afternoon would puzzle Dave Golding and nag away at his mind for all that time. Why had no one tried to save Arthur? Or had someone? Why did he allow himself to be talked into retaining his seat in the van? Could he have made any difference? Did he imagine the van? The original inquest into Arthur Horrocks’ death was concluded in precisely two hours, with minimal witnesses and a simple conclusion: accidental death.

There had been a stoic acceptance of that. Susan Horrocks missed her husband desperately but did not join either of the two groups who have campaigned for the facts - the Hillsborough Family Support Group and Hillsborough Justice Campaign. It was after the ordering of new inquests that the family established contact with solicitor Ruth Bundey, of Ison Harrison, and barrister Terry Munyard of London’s Garden Court Chambers, who is a founding member of the INQUEST charity.

Bundey and Munyard began the task of helping the family to fill the gaps. The parallel Operation Resolve, a criminal investigation into the disaster, pointed them towards newfound BBC colour footage which they had never seen. It captures Horrocks being laid on the football touchline and followed out of the pen by his brother Malcolm – unmistakeable by his unusual gait and bright green jumper. St John’s Ambulance officers move towards the pair, attempt to resuscitate Horrocks, while his brother kneels beside him, takes his hand and speaks. All to no avail.

Night had set in before Malcolm Horrocks was taken back to the football ground to identify his brother - who was, and would be known in years of subsequent correspondence, as ‘No 92.’ Golding had gone his own way – by bus to a local Boys’ Club where he was told families were gathering in search of lost friends and relatives. It was a Godforsaken place – a hot, oppressive, windowless shell remembered by Golding for the unbearable noise within. Police officers provided tea and biscuits and then got around to their key question: asking relatives how much alcohol they and the individual they mourned had consumed that day.

Eventually Golding’s thoughts drifted back to the van and the friends with whom he’d set out that bright day. “I’ve got to get back,” he thought and took a bus to Oughtibridge. It was there that the owners of the kitchen showroom, Sue and Steve Hill were looking out. “Your group are upstairs,” Sue Hill said, opening the door as he approached, and it transpired that the flat above the shop had become a sanctuary for them all.

Only in the past two weeks has it emerged that Hill, who had connected the parked Transit van to the catastrophe unfolding down in the city, had offered another form of help. He approached the first of the group to return – Golding’s friend Alan Pybis – and took him to the ground to find the others. They located Malcolm Horrocks. Hill took him to the stadium to identify Arthur Horrocks, whose funeral the Hills would later attend. The families have since met each April for a number of years.

Other members of the Horrocks family joined what was a vast exodus of vehicles from Liverpool to Sheffield that Saturday night, to bring home the survivors. Keith Horrocks was too devastated to drive the works Transit van. A smaller group returned to Arthur’s sister’s home in Liverpool’s West Derby district, where they began to come to terms.

It has been testament to the quiet resolve of Susan Horrocks that she returned to work in time and picked up a life as a single mother, raising sons who have done well, with careers in computing and retail. She remarried, though only briefly, and in time was able to leave that home they had made, moving six miles across Wirral, to the village of Bidston. She was in court to hear yesterday’s judgement delivered and evidently felt some sense of an ending at last. “It draws a line for us,” says Golding. “It gives us some answers. It won’t bring him back though. He always grabbed life and loved it and we’ll never know what might have lay ahead for him. We still miss him enormously.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments