‘Hangry’ worms ‘make risky decisions’ when they need to eat, study shows

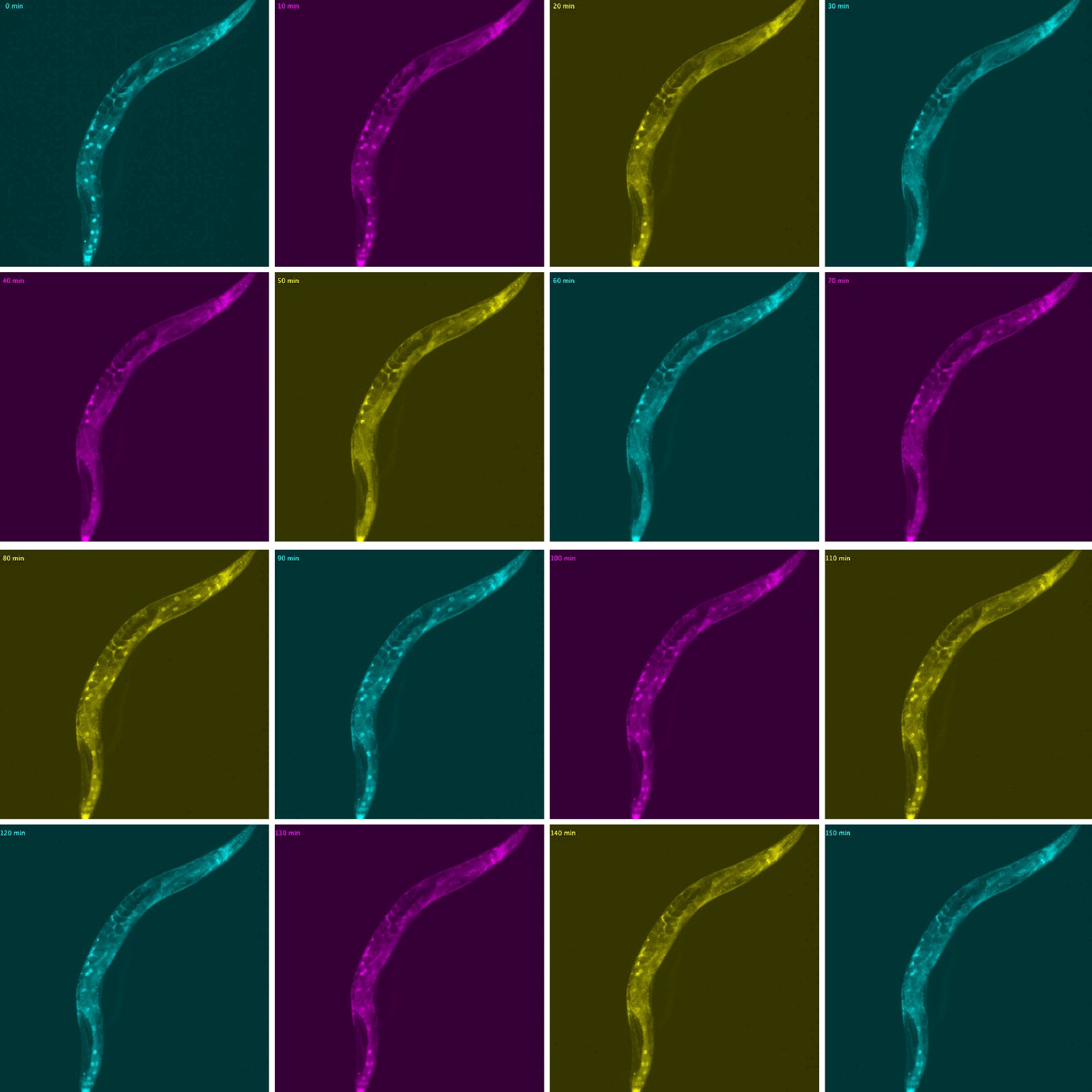

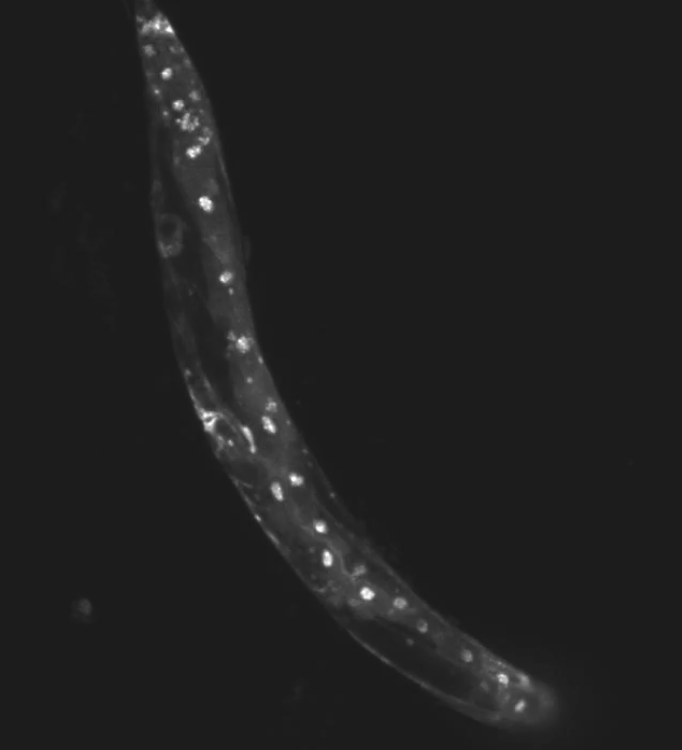

The team used a tiny worm to understand how hunger leads to behavioral changes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have dug deep to find the reason why we act irrationally when we are ‘hangry’- hungry and angry.

Studying worms, the researchers from the Salk Institute discovered that proteins in intestinal cells move dynamically to transmit signals about hunger, which pushes worm to cross toxic barriers for food.

The scientists believe that this finding can also be applied to humans which would explain why we may do drastic things in order to get a meal.

Sreekanth Chalasani, senior author of the study, said: “‘Animals, whether it’s a humble worm or a complex human, all make choices to feed themselves to survive.

“The sub-cellular movement of molecules could be driving these decisions and is maybe fundamental to all animal species.”

The team used a tiny worm called Caenorhabditis elegans as a model to understand how hunger leads to behavioral changes.

In the study which is published in PLOS Genetics, the researchers created a barrier of copper sulphate – a well-known worm repellent – between the hungry worms and their food.

When the worms were deprived of food for two to three hours, they were more willing to cross the toxic barrier to reach the food, compared to well-fed worms.

Using genetic tools and imaging techniques, the researchers investigated the molecular mechanism behind this behaviour.

In the well-fed worms, transcription factors- which are proteins that turn genes ‘on’ and ‘off’ – could be found in the intestinal cells’ cytoplasm.

When activated, however, they move into the nucleus.

But in the hungry worms, these transcription factors, called MML-1 and HLH-30, shifted location back to the cytoplasm.

When the scientists deleted these transcription factors, hungry worms stopped trying to cross the toxic barrier which demonstrates they key role that MML-1 and HLH-30 play in controlling how hunger changes animal behavior.

The researchers also found that when MML-1 and HLH-30 are on the move, a protein called insulin-like peptide INS-31 is secreted from the gut.

INS-31 peptides then bind receptors on neurons to relay hunger information and drive risky food-seeking behavior.

“C. elegansare more sophisticated than we give them credit for,” says co-first author Molly Matty, a postdoctoral fellow in Mr Chalasani’s lab.

“Their intestines sense a lack of food and report this to the brain. We believe these transcription factor movements are what guide the animal into making a risk-reward decision, like traversing an unpleasant barrier to get to food.”

The team believe that in the future, these findings could provide insight into how other animals, such as humans, prioritise basic needs over comfort.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments