Hanged for murder: Fiftieth anniversary of last people to be executed in UK

An unheralded walk to the gallows that proved a milestone for justice

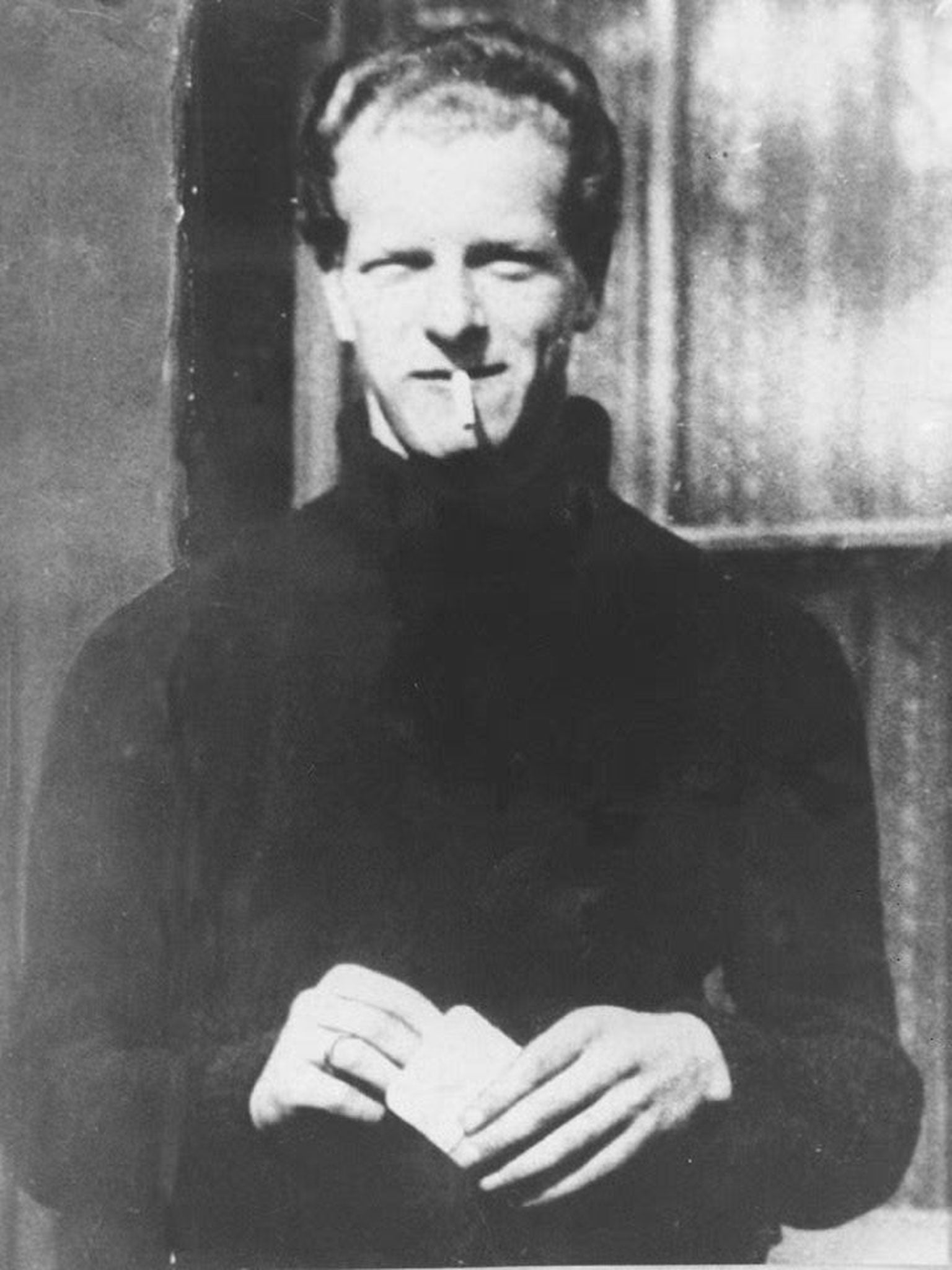

When, at 8am on 13 August 1964, Peter Allen and Gwynne Evans took a short walk to the gallows to be hanged for murder, the deaths of two hapless petty criminals were little mourned and little noticed.

The executions merited only a few lines in a couple of daily newspapers. Everyone expected more hangings would follow.

Instead Allen and Evans became the last people to be executed in Britain. Wednesday this week will be the 50th anniversary not just of their deaths, but of a major milestone in the history of British justice.

The death penalty for murder was suspended for a trial period the year after they were executed. In 1969 it was abolished altogether by a vote in the House of Commons, which won an overwhelming majority and loud cheers from the public gallery.

So a killing characterised more by incompetent desperation than anything resembling cold-blooded calculation acquired a significance few could have imagined at the time.

Needing money to pay off magistrates fines of £10 imposed on them for earlier thefts, the two jobless men had driven to the home of Evans’ former workmate John West, 53, in Seaton, Cumbria, to request the loan of “a few quid”.

Mr West refused to give them any money. His stabbed and battered body was found the next day. Tracing the two suspects was hardly difficult. Evans had left his raincoat at the scene, with a medallion inscribed with his name.

Letters from both men’s mothers begging the Home Secretary Henry Brooke to grant clemency had no effect.

At Strangeways, Manchester, Evans, 24, was led from his cell by Harry Allen, who always wore a bow tie for the job as a sign of “respect” and once claimed he “never felt a moment’s remorse” for his executions.

Thirty-five miles away in Walton Jail, Liverpool, Allen, 21, shouted “Jesus” as he was led to the gallows by his executioner Robert Stewart.

Former prison officer George Donaldson who witnessed the execution, told the makers of the ITV documentary Executed: “At the last minute he seemed to make some sort of effort to throw himself, but he didn’t get the chance. The lever dropped, the door opened and down he went. It was all over. “

From murder to double execution had taken just 18 weeks. It was too late for Evans and Allen, but an abolitionist campaign that dated at least as far back as the formation of the National Council for the Abolition of the Death Penalty (NCADP), in 1923 – after the dubious execution of Edith Thompson – was beginning to bear fruit. It was fuelled by cases like that of Derek Bentley, a 19-year-old with a mental age of 11 who was hanged in 1953 for the murder of a policeman, despite not having fired the fatal shot. The officer had told Bentley’s accomplice to hand over the gun, and the teenager had uttered the highly ambiguous phrase: “Let him have it.”

Also in 1953 it was discovered that the Rillington Place serial killer John Christie had been the real murderer of Beryl Evans and her baby daughter Geraldine. Mrs Evans’ husband Timothy had been wrongly hanged in 1950.

Mr Evans’ sister Maureen Westlake told the Executed documentary, to be broadcast on Tuesday night: “The last time I saw him, he did look like a 10-year-old. His face was all pale. He waved and said, ‘cheerio’.”

“It’s the Government that murdered Tim. Not killed him. Murdered him.”

In January this year, a poll found that 54 per cent of British people want the return of the death penalty.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks