Terminally ill ‘Dr Death’ Gunther von Hagens wants his corpse displayed in exhibition of dissected human bodies

Parkinson’s-sufferer behind new London museum asks to have his hand outstretched to greet visitors after his death

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The creator of a controversial new exhibition of dissected human body parts has reiterated how he wants his corpse to be posed in its entrance with his hand outstretched to greet visitors.

Gunther Von Hagens spoke to The Independent ahead of the opening of the Body Worlds exhibition in London, which will put on permanent display human limbs, organs and skeletons preserved through the “plastination” process he pioneered.

Dr Von Hagens was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease 10 years ago, leaving him with reduced motor skills and limited speech. With the help of gestures, he was still keen to communicate with those visiting his exhibition.

He strikes a pose as his son and commercial director, Rurik, laughs next to him.

“He is always changing his mind about where he wants to be displayed,” Rurik von Hagen says. “Before, he wanted to be cut into slices because he liked the idea of being in multiple places at once.”

Dr Von Hagens’ Body Worlds has attracted controversy, acclaim and more than 47 million visitors as it toured the world over the past 23 years, but this weekend will see it take up permanent residence in the London Pavilion in Piccadilly Circus.

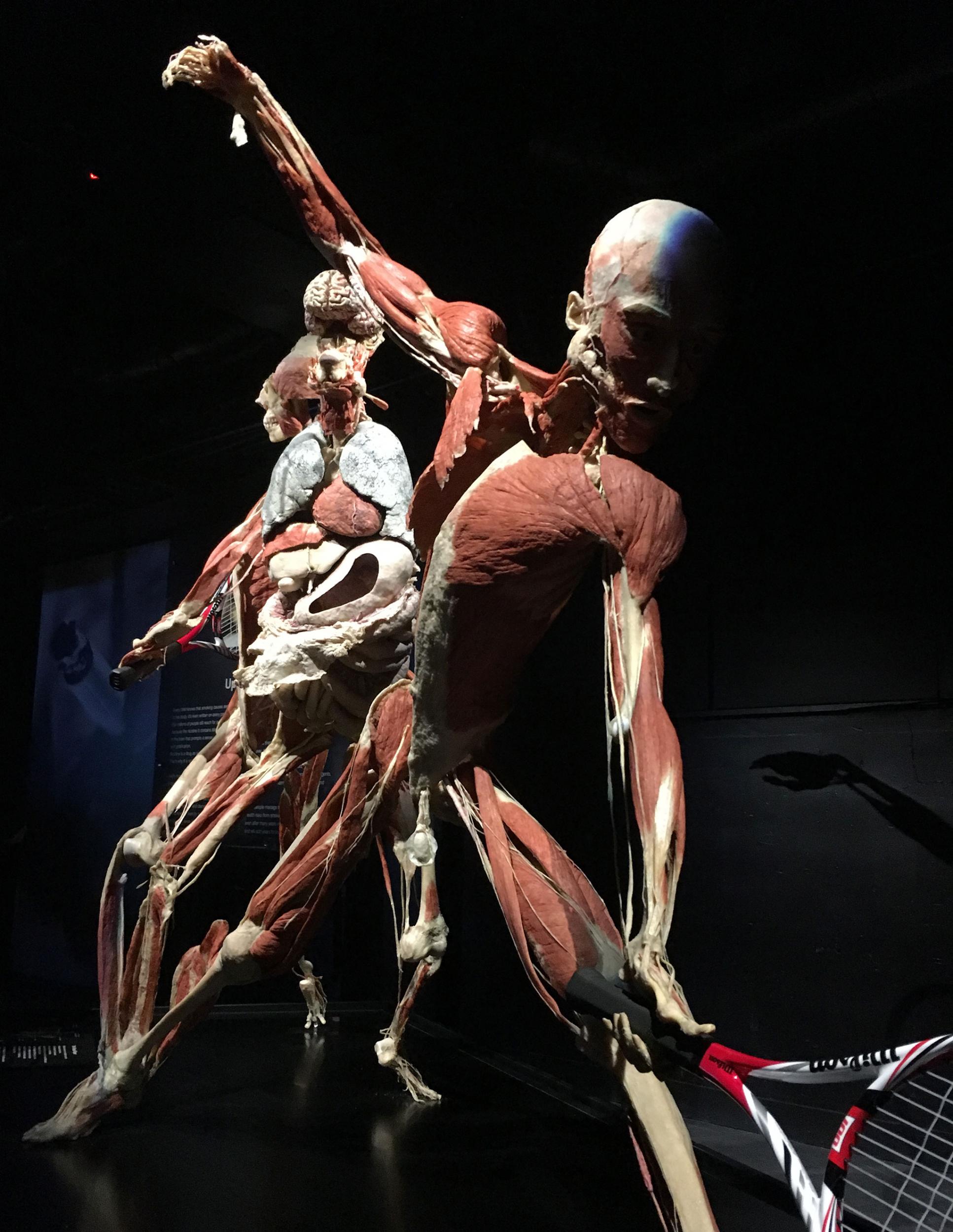

The exhibition is an uninhibited exploration of the human anatomy, made up entirely of body parts preserved using “plastination”. Once skin and tissue have been removed, the remaining muscles, organs, blood vessels, nerves and bones are fully preserved. The body parts themselves are then positioned in unnervingly lifelike poses – reminding the onlooker not just of the miraculous mechanisms people take for granted every day, but also the fact that the clock is ticking on their own mortality.

The London Pavilion now houses deceased tennis players, dancers, gymnasts, and even a group of bodies engaged in a poker game, inspired by the James Bond film Casino Royale. The centrepiece of past collections, consisting of a rearing horse with two riders – one holding his own brain in one hand –has maintained its place as a centrepiece. Some exhibits are blessed with their muscles and skeletons, others have been left with only an intricate web of blood vessels or nerves.

“We are anatomists and we want to show the body interior in a very dramatic way, and in a very lifelike way,” says Dr von Hagens’ wife and head curator, Angelina Whalley.

“I would say this is our flagship. We have never accomplished an exhibition of this magnitude, it’s really huge.”

The new, permanent exhibition places a new weighting on the importance of food, exercise and happiness to overall health. The aim of the project has always been preventative healthcare, Dr Whalley adds.

One gallery shows a comparison between healthy lungs and the blackened lungs of a smoker, while another contains a dissection of cancerous bones. A thinly sliced brain allows viewers to identify the dark stain of a stroke. In one section, paramedics encourage visitors to practice their CPR skills on a dummy, while a nearby cabinet displays a pair of bodies, one seemingly attempting to revive the other.

It all adds up to a sobering experience. According to its website, Body Worlds leaves 68 per cent of visitors with “valuable incentives for a healthier lifestyle”, while 79 per cent feel “deep reverence for the marvel of the human body.”

“People come with hesitations, they might not have ever seen a corpse before,” says Dr Whalley – while her husband imitates the shocked face of a visitor.

“We are physicians, we are so used to it, we don’t even recognise what a privilege it is to have a look at a real human body interior, but when you walk through the exhibit you can feel it.”

The German couple, who met in a dissection class at Heidelberg University, have collaborated on Body Worlds since its beginning in 1995.

“Gunther is the inventor of the technology,” says Dr Whalley. “He is the creator of all these beautiful specimens. I took them and put them into an exhibition environment.”

“We very much pay attention not only to the anatomical dissection but also try to come up with very lifelike poses so people can relate to them, and also to make the specimens more beautiful. Because if something is beautiful you do not necessarily shy away from it.”

Mr Von Hagen developed the process of plastination in the late 1970s, originally as a means of providing anatomical education props for universities. After he ran out of space in his Heidelberg laboratories, he rented several garages around the city to expand his plastination project. His son accompanied him as a child on trips to check on the “plastinating” organs.

“He always liked to think big,” Mr Von Hagens said. “Some people have toolkits in their garages, my father had plastination.”

The arduous plastination process begins with the injection of formalin, a tissue fixative, to stop the process of decay. Time is then needed to perform an dissection to remove skin and fatty tissue, while working out the muscles and the nerves and deciding which part of the body to prepare for show.

The body is bathed in acetone to remove any soluble fats before the central phase, in which a complicated vacuum process allows the water within each individual cell to become replaced with polymer, a form of silicone.

Before the body hardens, it must be positioned for display. A muscular male might be chosen for a sports pose, while a delicate female body might be positioned as a ballerina.

“The specimen speaks to you,” says Dr Whalley. “Faces are also extremely crucial for our specimens because we are so trained to look at peoples faces, and when you watch the visitors they also look at people’s faces, so they need to be appealing. They should not look ugly.”

A body donation programme established by Dr Von Hagens in the early 1980s, before the creation of Body Worlds, has supplied the couple with plenty of subjects. Similar to an organ-donation system, those wishing to participate in the programme register their intention to donate their body for the purposes of training and education after their death.

One full-body specimen will take around one year to complete, or 1,500 working hours. The extent of their preservation depends of the cause of death, the amount of decay that might have already taken place before the body reaches in institute in Heidelberg, and the diseases a donor might have suffered during his or her lifetime.

“We always consider that these specimens hold more or less forever, so these dissections need to be perfect, they need to look breathtaking,” says Dr Whalley.

Her husband gave her a smile and she added: “He always likes to say that they will last longer than the mummies of the pharaohs!”

Despite his difficulties walking and speaking Dr Von Hagens continues to research the means of body preservation, exploring methods that would allow “plastination” without the need for acetone, which is difficult to store.

When asked if he would ever stop working and retire from the project, his wife shook her head: “His heart is in plastination. He wouldn’t stop.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments