Yes, the ‘elitist’ Foreign Office needs a new look - but not by changing the old paintings

As former diplomats lead calls for the elitist department to be replaced, the colonial artworks from an imperialist past are the least of the Foreign Office’s worries, argues Anthony Seldon

Victorian foreign secretary Lord Malmesbury had had a particularly good lunch, but was not amused when he sauntered back to his desk in the old Foreign Office in Downing Street to find that the ceiling had disobligingly collapsed onto his desk.

The whole office was indeed in a sad state. When foreign dignitaries visited the building, they were given to nervously eyeing the plaster, which was being held up by temporary beams. “It is opening up the whole nation to ridicule,” lamented The Times.

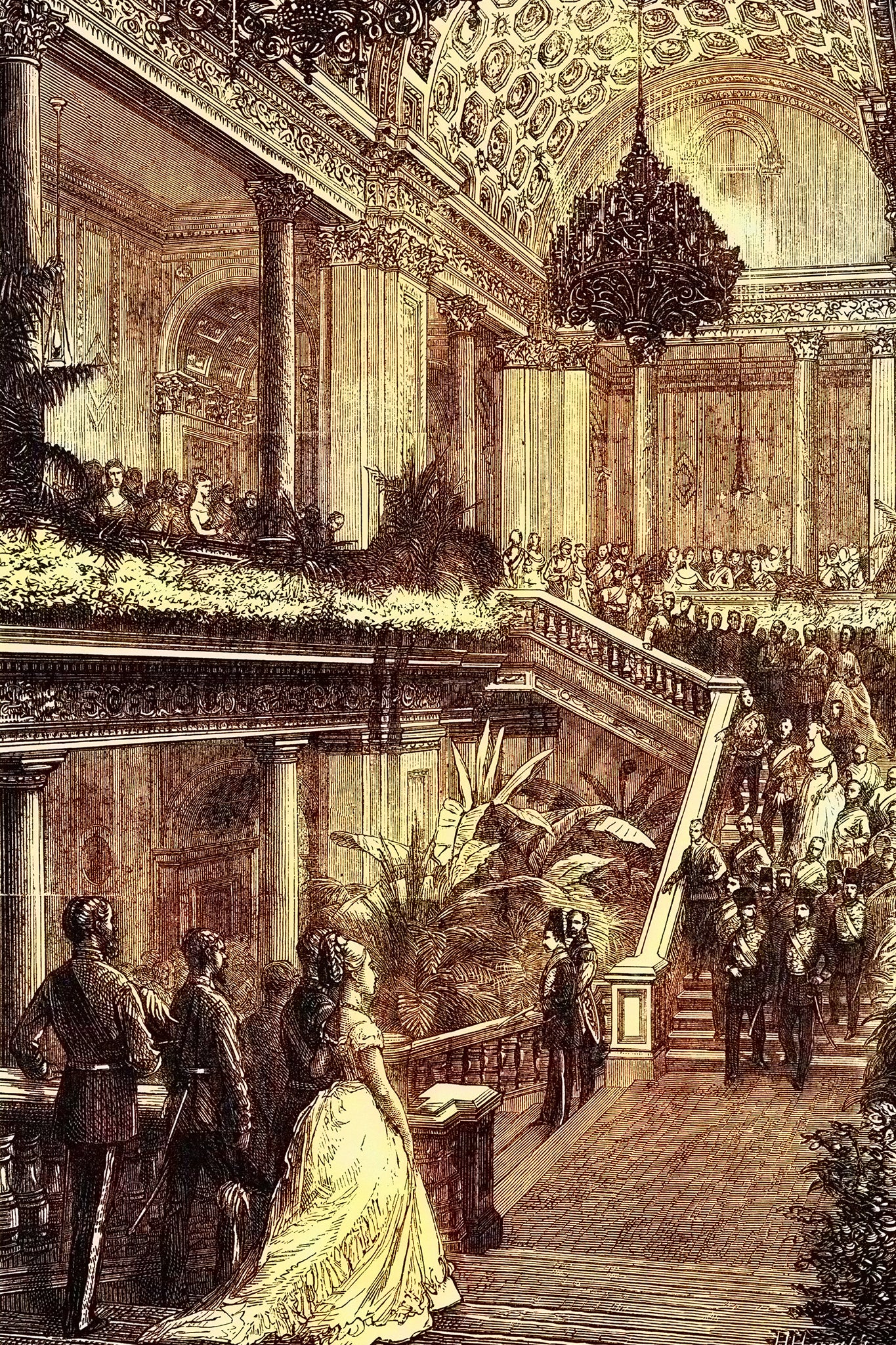

Reputational damage provided the impetus for the current Foreign Office building to be erected at vast expense. The 17th-century terrace houses that had been built at the same time as No 10 and No 11 by rogue property speculator George Downing were razed to the ground to make way for the grand pile designed by George Gilbert Scott, which opened in 1868.

Today, it is the Gilbert Scott building, along with the name of the office and its very work, that is at risk of ridicule in a new report: “The World in 2040: Renewing the UK’s Approach to International Affairs”, written by former cabinet secretary Mark Sedwill, ex-diplomat Moazzam Malik, and Foreign Office high-flyer turned Oxford head of house Tom Fletcher.

Coming as the latest in a long line of diagnoses of “the Foreign Office problem” dating back to the Duncan report of 1969 and before, this document certainly pulls no punches.

The entire Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (to give it its full title) is “anchored in the past” and “struggling to deliver a clear mandate”, it states.

It is insular: “All too often it acts like a giant private office for the foreign secretary of the day”. It is attempting to rely on traditional alliances with the US and Europe, and needs to learn from countries like Canada, Japan and Norway (ouch) about how to leverage its size and independence to be an influence on the world stage, blending Britain’s security interests with its trade, aid, development and climate-change ambitions.

Even the magnificent classical building comes under attack. Erected at the instigation of the politician Lord Palmerston, who did more than anyone to establish the British empire and its premier position in the world, the office gives a backwards-looking impression “with its colonial-era pictures on the wall”.

The author highlights, in an interview on BBC Radio 4, an incident in which an Irish diplomat was visiting the Foreign Office to take part in sensitive talks: “Towering over the meeting table was a portrait of Lord Trevelyan, who was famous for wanting to limit the UK’s financial exposure to the Irish potato famine. The significance of that was not lost on the Irish diplomat.”

The report provides a much-needed shot in the arm. It is not, of course, just the Foreign Office that is housed in a 19th-century building – and trying to run the government in a manner laid down in that century – but Whitehall at large, which a report published by the Institute for Government last month argued is no longer working.

Given the likelihood that a Labour government will be installed following the general election later this year, it is an opportune moment to be considering the question of the way the country is governed and the way in which Britain wants to connect with the rest of the world.

For the hundred years following the erection of the new Foreign Office building in the 1860s, Britain was a major force in the world, and the position of foreign secretary was second only, in the government, to that of prime minister.

But developments in communication technology and the speed of international travel have meant that foreign ambassadors, and the post of foreign secretary, can seem redundant.

Since the 1980s, the prime minister has been the key figure in the conduct of Britain’s foreign policy, and the post of foreign secretary has shuffled down the pecking order – a slippage that the incumbent, David Cameron, is trying to reverse, if only in the short term.

Now is exactly the moment when Britain needs to rethink its government in preparation for a world dominated by AI, climate change, concerns about energy security, and the shift in global power eastwards.

Many of these questions were explored in the seminal Integrated Review of 2021 (revised in 2023), written by Boris Johnson’s best hire you’ve never heard of, John Bew.

His plan included significant investment in AI and cyber capabilities, which would ensure the UK remained one of the biggest defence spenders in Europe. With proper investment, Bew suggests, we could be the convener “of the next 10 largest powers”, pointing to an expansion of the G7 group to a “D10” of democratic powers (G7 plus India, Australia and South Korea).

We certainly don’t need to be trashing Foreign Office diplomats, as governments have repeatedly done. Their quality, along with their judgement, is often far better than that of their political masters. We need, rather, to empower them, and to bring the worthy but tired British Council under their auspices.

British language, history and culture deserve to be much better known across the world. Britain needs to be proud of the times when it has been at its best, in order to balance those aspects of its history of which it should be ashamed. That most certainly means remaining in the Victorian edifice.

Britain has a uniquely important role in the world up to 2040, and long after that. With the progressive loss of moral authority emanating from the United States, whether Donald Trump is re-elected or not, the space is wide open for our nation to provide leadership based on the principles of self-determination, democracy and liberty that Britain has proudly expounded.

To achieve that, it needs to attract the brightest and best young people to join it, and it needs to retain and inspire them with a sense of mission and idealism.

Decamping the office to a drab, modern, open-plan space will do little to achieve that. There is so much to admire and be inspired by in the architecture of the present building.

Much better to let those who work in this office be reminded every day of the sins of the past, and resolve that they will never repeat them – that they are there to do a better job, for Britain and the world.

Sir Anthony Seldon is the author of ‘The Foreign Office: The Illustrated History’, ‘The Impossible Office? The History of the British Prime Minister’ (updated version out now) and ‘Johnson at 10: The Inside Story’

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments