Britain tried to kill Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1918 with secret RAF bombing raid, reveals archives

Exclusive: 'In Germany it might well have turned the increasingly unpopular Kaiser into a martyred war hero and so perhaps even have saved the monarchy from collapse'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Remarkable unpublished evidence has revealed that in the final year of the First World War Britain attempted to kill Germany’s leader, Kaiser Wilhelm II.

The secret mission failed – but only just.

The evidence – largely unpublished documentation in the RAF Museum’s archives and documents in a private archive in France – show that exactly 100 years ago this Saturday, a squadron of 12 bombers took off from an airfield near Boulogne to bomb a French chateau which, intelligence work had revealed, was being used by the Kaiser as his secret Western Front operational residence.

The full story – partly revealed in a new book just published – started in late March 1918 when the German army launched the first of a series of major new offensives against the Allies.

The massive attacks were initially successful – but nevertheless some German soldiers were captured by the Allies. Some of these German PoWs were interrogated by French Intelligence – and one of them revealed to his interrogators that the Kaiser had just taken up residence at a chateau immediately outside a small French village called Trelon, three miles from the Belgian frontier.

By coincidence, one of the intelligence section’s interpreters on the staff of the famous French general, Philippe Pétain, was the owner of that chateau. In mid April 1918 he was given the job of interrogating the German prisoner-of-war in more detail – and, by using local knowledge, to check the veracity of the revelation.

This interrogator (a French officer named Frédéric de Merode) and his commanding officer then went to tell Pétain what they had discovered.

At some stage – probably in May and presumably in conjunction with the British – an "in principle" decision was taken to bomb the chateau. Indeed, De Merode (the chateau owner) was asked by the French military to give them permission to bomb the building. Patriotically, he agreed.

German sources reveal that the Kaiser stayed there on at least three occasions – from 21 March to 2 April; from 5 April to 15 April; from mid May to 1 June and possibly from around 26 April to around 1 May.

It may well be that British intelligence wanted to learn further details before any final political or military green light could be given to try to kill the Kaiser.

After all, they would probably only get one opportunity. If it failed, he would nevertheless realise that the Allies knew exactly where he was living and he would therefore promptly change his Western Front operational residence.

British intelligence officers in Amsterdam in neutral Holland had frequent contact with an underground espionage network in German-occupied Belgium and northern France called La Dame Blanche (The White Lady). It is known that the LDB had agents in the Trelon area – so it is likely that further information on the Kaiser’s movements was passed on (via Amsterdam) to British intelligence HQ in London. However, there was always a time delay – so information was always slightly out of date.

At the same time that the Allies discovered the precise location of the Kaiser (and more importantly realised that he was within bombing range), the German Spring offensive was giving British and French forces a terrible battering. The Germans were succeeding in pushing the Allies back more than 40 miles.

What’s more, in late May, at the battle of Chemin des Dames, the Germans captured 45,000 Allied troops and 400 field guns. For the Allies, it was a catastrophe. At that stage, even in late Spring, 1918, they must have feared that the Germans might even win the war.

So, it was in those dire circumstances that the French and the British appear to have finally decided to try to kill the German emperor.

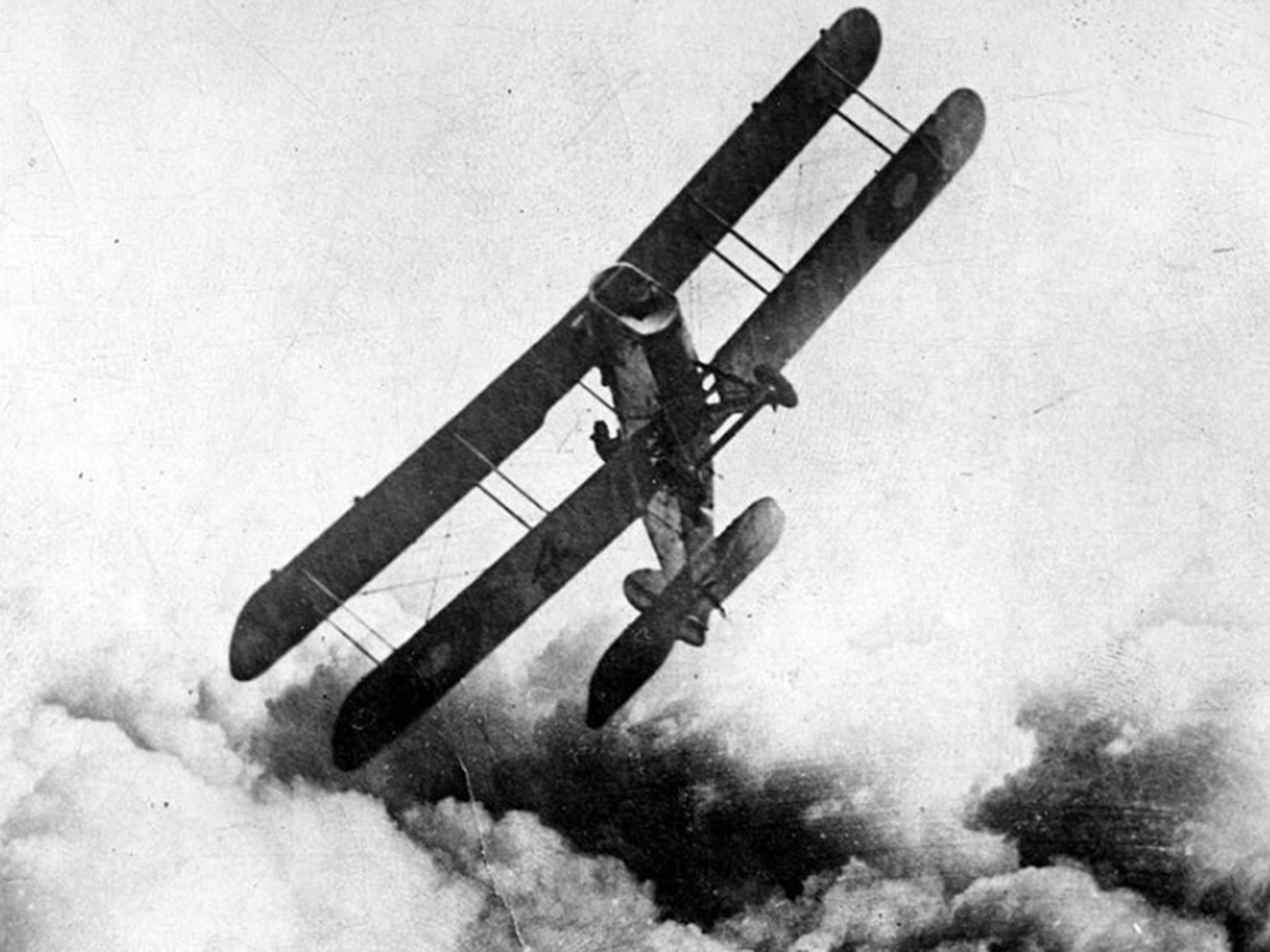

Having taken off from Ruisseauville Airfield (near Boulogne-sur-Mer) at 4.50am on Sunday 2 June, 12 RAF De Havilland-4 bombers reached the Kaiser’s secret Western Front residence at Trelon at 5:25am. They dropped up to a dozen 50kg bombs and up to 24 11kg ones.

However, unbeknown to British Intelligence, the same German military successes that had probably triggered the bid to kill Kaiser Wilhelm, had also led him to leave the chateau to congratulate his generals at the front. As a result, he had left his Western Front operational residence 19 hours before the RAF struck.

What’s more, the British aircraft chose to attack at an altitude of only 500 feet – and to do so in single file. As a result the smoke from the initial few bombs billowed skywards and prevented many of the succeeding pilots from seeing their target.

The chateau itself therefore remained largely unscathed – although the Imperial cars parked in front of the building were destroyed, their petrol filled tanks and rubber tyres no doubt contributing to the, in this case quite literal, fog of war.

However, as the bombing raid unfolded, one of the emperor’s Imperial trains was heading at high speed along the private railway line that led to the chateau’s private station. The British aircraft succeeded in pumping 800 rounds of machine gun fire into its five carriages. It’s likely that a number of people on that train were killed and injured. But the Kaiser was relatively safe and sound – 25 miles away.

But ironically he was not in a good mood. For by the time he had reached the front, the German advance had finally been repulsed. Covered in dust, he confided to his aides just how disappointed and downcast he felt.

Bizarrely, it seems that even four days after the RAF attempt to kill him, nobody had informed him or his aides about the raid on his secret Western Front residence. Indeed, the diary of a senior adviser, records a discussion in which they reflected on how dangerous it was where they were (by the side of a large ammunition store) and how it would be better to return to the safety of the chateau. In the end, however, they just moved a few miles away.

It’s almost certain that the Kaiser must have learned about the raid shortly after that move – for a senior aide’s diary indicates that he never again returned to the chateau at Trelon. Now that the Allies knew he had been staying there, it had obviously become a potentially very dangerous place for him to base himself.

The attack has remained largely unknown since it took place exactly 100 years ago. The British and the French obviously did not want to tell the world about a failed mission – and, of course, the Germans did not want to advertise the fact that their emperor was still alive due only to good luck.

Knowledge of some aspects of the attack lived on in and around the village of Trelon and in the memories of the descendants of some of those pilots and others involved. But it does not feature in any major published works on First World War history or on the early days of the RAF.

The author of the book, The Kaiser’s Dawn, due for release this weekend, found out about the secret raid from the grandson of one of the RAF pilots.

“As president of the Guild of Battlefield Guides, I was leading a tour of the Western Front and became aware of some unpublished First World War RAF documents. I was astonished. I had stumbled across an historically important treasure trove that revealed secrets which have been largely hidden for a hundred years,” said writer, military historian John Hughes-Wilson, a retired colonel in British Intelligence.

But there are still three major mysteries surrounding the attack.

Trying to assassinate your enemy’s head of state, especially a royal one who was the British king’s first cousin, was to put it mildly, a very serious, sensitive and potentially controversial matter. So who was it in Britain who actually authorised the attack?

It’s very likely that the British prime minister, David Lloyd George, would have had to authorise the mission, especially as it involved the RAF. But there is no proof that he did so, or even that he knew about it beforehand. Deliberately trying to kill an enemy head of state was a very rare event in history

it is not the sort of thing civilised governments were supposed to do. After all, it was an accusation of state complicity in the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand – not even of a head of state – that had triggered the war in the first place.

Certainly there is no evidence that Britain ever tried to assassinate a major enemy’s head of state in the many wars of the 18th century, in the Napoleonic Wars of the early 19th century or even in the Second World War. Indeed, the only British plan to assassinate Adolf Hitler was, in the end, vetoed by Britain’s prime minister, Winston Churchill. The raid on Trelon in 1918 is therefore potentially unique – and an aberration from normal political and military convention.

The second mystery is the timing of the raid. Was it triggered by German military success in March, April and May 1918. Was it therefore an act of Allied desperation? Or had it, in principle, been envisaged long before – only to be carried out when appropriate intelligence information came to light?

But the third mystery is a more mundane tactical one – but in a sense equally interesting. Why did the RAF attack in single file, when they might have been expected to realise that smoke would risk compromising a low level single file approach?

The chateau still stands – and is today a popular local tourist attraction. Remarkably, many of the key documents relating to the secret raid – including RAF pilots’ logbooks, a hand-drawn map of the target area and the original French Intelligence report – have survived unpublished in British and French archives.

“This is a sensational revelation and one can only wonder how world opinion would have reacted if the raid had been successful. In Germany it might well have turned the increasingly unpopular Kaiser into a martyred war hero and so perhaps even have saved the monarchy from collapse less than six months later, providing the defeated nation with an element of stability in an otherwise revolutionary situation full of future menace,” said the world’s leading expert on Kaiser Wilhelm II, Professor John Röhl of the University of Sussex.

John Watts, the grandson of one of the RAF airmen involved in the raid, believes that much more information on the raid must still exist in as yet un-studied files in archives in Britain, France and possibly Germany.

“My grandfather’s role was always part of family folklore. The remarkable new details now emerging from sources in northern France and RAF files is at last beginning to reveal what really happened,” said Mr Watts, a West Midlands military history enthusiast.

‘The Kaiser’s Dawn: the untold story of Britain’s secret mission to murder the Kaiser in 1918’ by John Hughes-Wilson (Unicorn Publishing)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments