Looking for an award-winning pet? Maybe it’s time to consider... a rat

Believe it or not, rats were once the pets of choice for well-bred ladies, Beatrix Potter being among them. In his new book, Joe Shute looks at why our relationship with these clever rodents became so difficult and talks to the people who organise ‘Crufts for rats’, hoping to change our minds…

Holding my pet rat Molly one evening in my lap as she devoured a chip of dried banana, her little heart pumping against my thigh, I wondered how many beats she had left.

She was by now just over two years old and beginning to show her age (rats live until three if they are lucky). Normally so immaculately groomed, her soft grey fur was increasingly unkempt. Her tail drooped behind her like a loose shoelace.

Her sister, Ermintrude, was also visibly ageing. A few months previously she had developed a small lump on her chest. Female rats are prone to fibroadenomas (benign tumours in their mammary glands), which are also common in humans. The lump was giving her no obvious discomfort and she was as energetic and affectionate as before, still able to groom.

We needed expert advice. I had previously been in touch with the National Fancy Rat Society (NFRS) about attending one of their shows.

According to their events page, one was coming up at a community hall in Scawsby, Doncaster, not far from where we lived. While we supposed our two ageing rats would not pass muster under the scrupulous gaze of the show judges, we thought it would be a good place to meet some breeders and to canvas opinions about how best to care for Molly and Ermintrude in their dotage.

The National Fancy Rat Society was formed on 13 January 1976, and today the NFRS is the Crufts of the rodent world, celebrating the cream of Britain’s rats.

The society hosts shows across the country at which a judging panel awards rosettes for the health, vigour and beauty of various breeds based upon strict criteria.

The Scawsby show is one of the less high profile in the NFRS calendar, but when we arrive the community hall is nonetheless busy with people – and rats.

The entrants are lounging around in plastic boxes on a generous bed of sawdust with scraps of cucumber to nibble (and keep them hydrated). The judges occupy a seat at the head table, studiously inspecting the rats before them.

Stalls selling rat-themed clothes, jewellery and soft furnishings to adorn cages are dotted about the room. We buy a new bed for our rats with a pocket stitched into it to enable them to hunker down together inside.

The world of the fancy, as enthusiasts call it, is a small one, with almost all of the 50 or so people inside the room appearing to know one another. We sit and start talking to one breeder, Julie Oliver, who has just been presented with two rex rats, known for their ruffled fur and curly whiskers.

Julie, a primary school teacher, is a veteran of the rat show scene. She has been breeding since 1998 and at any one time, estimates she has an adult population of around 50 rats living in a converted garage in her Cambridgeshire home. She has previously displayed a couple of gold championship rats and says she has several plastic boxes at home filled with rosettes from previous shows.

On the eve of a show, Julie carefully clips the claws of the rats she is intending to enter. Some of the paler varieties require having their tails cleaned using a toothbrush and washing-up liquid.

Otherwise, the meticulous personal grooming of rats means she does not need to intervene with their already glossy fur. The condition of the fur, she explains, is down to their diet. Julie feeds her rats four different types of breakfast cereal, seeds and a rabbit food base.

There are no breeds in rat shows, just varieties. This is because the diverse array of pampered rodents luxuriating in their cages before me, their fur ranging from silver to a rich cinnamon to a deep steel blue, all belong to one single species – the common sewer rat.

The roots of this curious genesis lie in 18th-century Japan where during the Edo period breeding rats to produce different coat colours was a popular pursuit.

So popular, in fact, that several guidebooks on the subject were produced. The most famous text is the Yosotamanokakehashi, published in 1775. As the earliest known text on breeding rats, the book is a bible of the fancy.

There are illustrated descriptions of various types, including the “red-eyed white” (an ancestor of the modern-day lab rat) and the rare “black-eyed white”, prized as a portent of prosperity.

Other varieties featured in the book are the “bear rat” (black with a white crescent on its chest) and “fox rat” (with a white belly and ruddy back). The book ends with a list of five pet shops that traded rats in what is today the city of Osaka, four of them located on a single street. Evidently, the trade in rats was popular enough for money to be made.

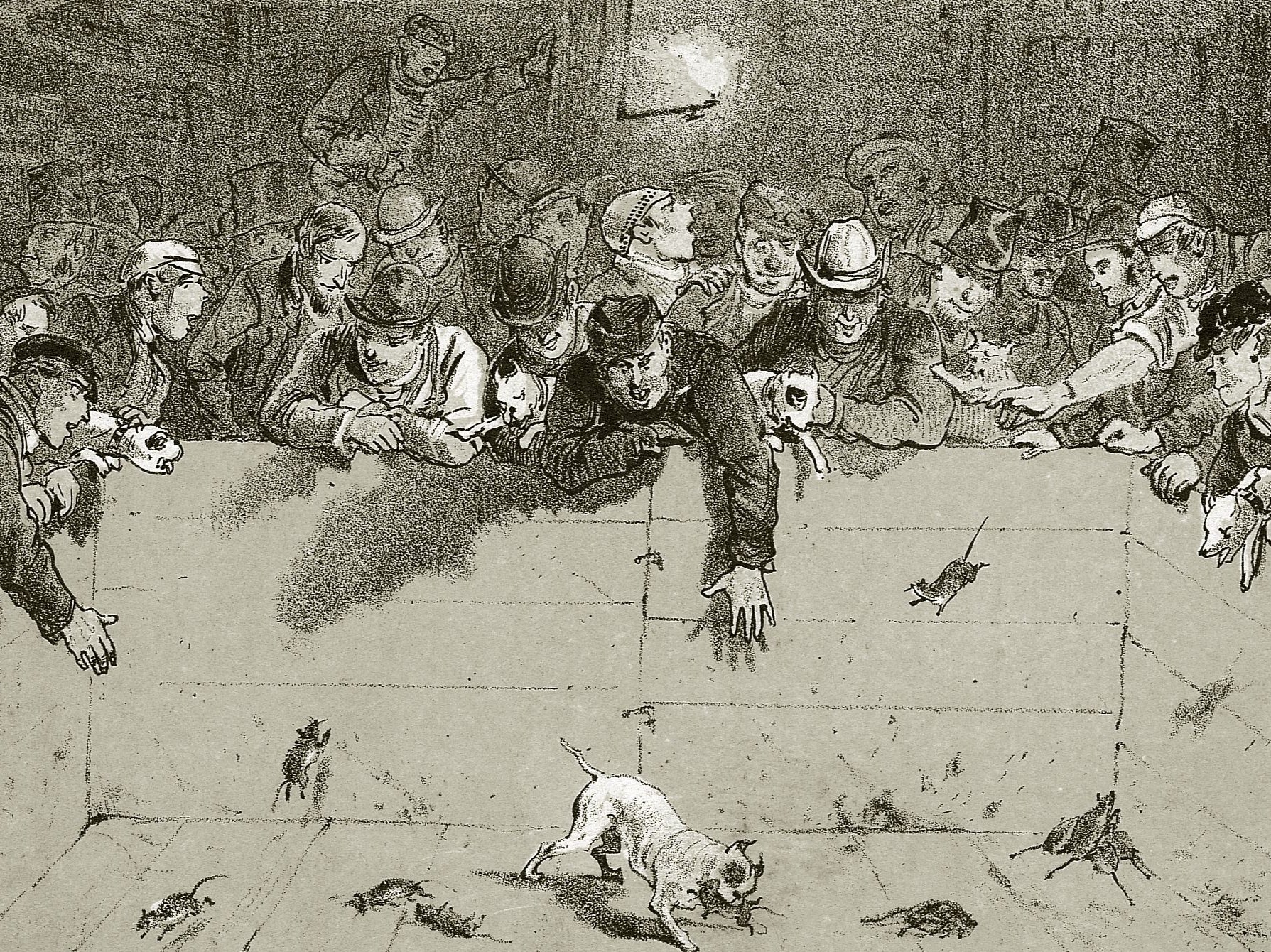

The story of rat breeding in the West is a darker one, which speaks to our troubled relationship with rodents. The first real evidence of it dates back to the rat pits of the mid-19th century – miniature colosseums constructed in pub back rooms where drinkers would set dogs on rats and gamble on how many they could kill.

Such was the thirst for the blood sport that a constant supply of rodents was required to be killed in front of the baying crowds.

Changing the negative popular perception of rats is a preoccupation of all those involved in the NFRS

It was presumed that country rats were far less disease-ridden than their urban counterparts, whose bites could lead to unpleasant infections, and domesticated ones were even better.

Rat breeding soon led to a trade beyond the pits. Following the first scientific trial involving rats in 1828, from the mid-19th century, they were increasingly used in laboratory experiments. A pet rat also became something of a sought-after accessory among the upper classes. The ratcatcher Jack Black, who operated his own breeding programme, boasted that he would sell them to “well-bred young ladies in squirrel cages”.

Among those to own a pet rat was the author Beatrix Potter, who had an albino called Samuel. Potter, who was in her early forties at the time, adored her rat, to whom she dedicated her 1908 book, The Tale of Samuel Whiskers.

She also produced a number of drawings, named “Studies of a tame rat ‘Sammy’ from life”. One of the drawings, now held by the Victoria and Albert Museum, she entitled, “The peculiar dream of Mr Samuel Whiskers, upon the subject of Dutch cheese”.

Around the time Beatrix Potter took ownership of Samuel, the earliest rat shows were being held in Britain. According to Ann Storey, the club’s current president, the first time fancy rats were displayed was on 24 October 1901, by a woman called Mary Douglas at the Aylesbury Fanciers’ Show.

There were apparently 15 different rats exhibited in one class and Mary won with a black and white hooded variety.

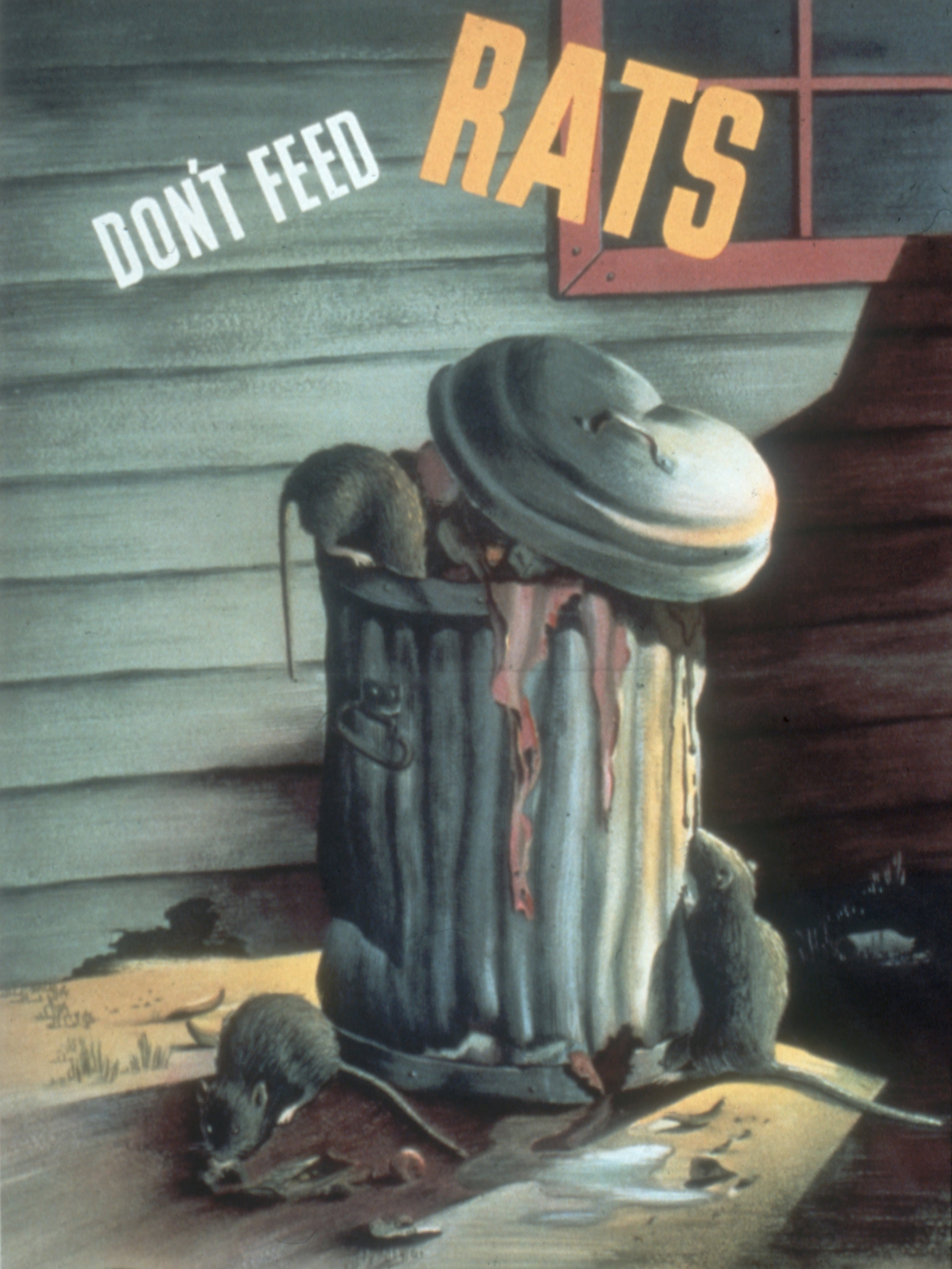

Following the end of the First World War, however, the rat fancy fell out of favour. Stories of horror from the trenches and the declaration of national war on the rat ushered in the Rats and Mice (Destruction) Act, which was passed in 1919.

With politicians and campaigners calling for the rat to be obliterated, it must have been difficult, if not considered heretical, to continue a society celebrating the beauty and gentle nature of such a demonised creature.

Changing the negative popular perception of rats is a preoccupation of all those involved in the fancy rat circles. As well as attending shows, today’s NFRS members also serve as public relations officers for rats.

They attend agricultural events around the country, attempting to introduce farmers to a different side of the rodent. Julie Oliver has previously put in a shift at county fairs.

So too, Kate Rattray, a fellow rat breeder who also works as a GP. Given her profession, I ask her about rat bites. She admits that she has been hospitalised before from a particularly nasty nip, but blames herself entirely.

Otherwise, she and the fellow breeders I talk to say a rat bite is extremely rare. When she used to work as a junior doctor on hospital wards, Kate says, people were far more likely to come in with other animal bites.

According to figures released under a freedom of information request to Scotland’s local health boards, between 2011 and 2014, of the 10,953 animal attacks that left people requiring hospital treatment, 7,731 involved dogs and 41 cases involved rats. And yet we are, broadly speaking, a nation of dog-lovers and rat-haters.

Perhaps it was naive of me to assume we would visit the show and not return with a stowaway, but word soon gets around the Scawsby community hall that we are in need of some more rats. The best thing to keep a rat young, we are continually told as we chat with the breeders, is to introduce new blood.

We are introduced to a Sheffield breeder, Lily Hoyland, who as we speak produces from behind her chair a cage containing two young rats. They are sisters, although markedly different. One is a silky black with a white belly and diamond marking on her face, and the other an agouti – the breed that most closely resembles a wild rat with chestnut, almost golden hair and a pale belly.

They will keep our elderly rats company, Lily says, and are ours for free. It doesn’t seem like we have much choice in the matter. As we leave, I wonder how many people walk out of Crufts with a couple of gifted dogs?

Lily hands over our new pets and gives us some advice on how best to introduce them. When we get home we carefully follow her instructions, thoroughly cleaning Molly and Ermintrude’s cage to remove traces of their scent and then putting all four rats together in the smaller carry cage to become habituated to each other.

We hold our breath as they first race up to each other and paw one another frantically as well as rubbing their snouts close to their fur.

Content that no blood is going to be shed, we decide to leave them overnight. The following morning all four rats are piled up together in a sleeping huddle, a mass of coiled tails and multi-coloured fur. Somehow, I realise, we now have a colony.

This is an extract from ‘The Disreputable Exploits of the Rat’ by Joe Shute, published by Bloomsbury and released on 12 April

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks