Denmark Place arson: Why people are still searching for answers 35 years on from one of the biggest mass murders in our history

The site of an attack that killed 37 people in August 1980 is to be demolished

Weeks from now, a demolition team will advance on 18 Denmark Place in central London. Part of a row of doomed houses on an alley off Charing Cross Road, the three-storey address will be consumed by the vast Crossrail development at Tottenham Court Road. As it crumbles, the last physical evidence of a forgotten disaster – one of the worst crimes of the 20th century – will turn to dust.

For Agnes “Paddy” Crossin, the house was a home from home, although she never knew its number. On a mild Friday night in August, 1980, the Belfast-born Londoner was drinking at a pub down the road in Soho, after a long day working as a cook on a building site.

“My friend Alex was out. Oh God, he was such a character,” she recalls. “In those days, after 11 was the end of drinking. Alex was like, ‘eh, we’ll go on up to the Spanish Rooms’. I said, ‘No, I’m too tired, I’m going home.’ So of I went, and off he went. It’s broke my heart for the past 35 years.”

The Spanish Rooms, also known as El Hueco (“the hole”), was an unlicensed bar on the top floor of No 18, which backs on to Denmark Street, the strip of guitar shops and music studios known as London’s Tin Pan Alley. It drew a mixed crowd – Brits, Irish, Jamaicans, a Libyan. For many, it was an escape from the rougher edges of London life. “Nobody had a second name,” says Paddy, who was 29. Now 64, she has come back to Soho from her home in south-east London to recall the night of 15 August. “You went up there, you called yourself what you wanted.”

Below the Spanish Rooms, and above a ground-floor store for hotdog trolleys, a separate club known as Rodo’s or El Dandy was popular with Colombians, many coming off shifts at restaurants and hotels to relax and dance salsa. Police were planning to shut down both clubs, which patrons accessed by shouting up for a key. But more than 150 people filled the rooms that night, talking and dancing behind boarded-up windows and locked fire escapes.

Not long after 2:30am, on 16 August, John “The Gypsy” Thompson, a Scottish-born small-time crook who fancied himself as an East End gangster, accused the Spanish Rooms barman of overcharging him for a drink. After a fight, Thompson took a cab to an all-night petrol station in Camden, 20 minutes away. He came back to Denmark Place with a can of petrol, poured it through the letterbox, and lit a match. Minutes later, 37 people were dead.

Paddy estimates she knew about 17 of the victims, 24 of whom died in the Spanish Rooms. “A few years ago I saw the fire brigade photos of the bodies,” she says. The pictures are horrific, showing a charred mass next to a blackened bar. Beer bottles stand without tops, their contents turned to steam. Only the skulls indicate the presence of people. “I’m looking at them thinking, oh God, is that Alex?”

If you have never heard of John Thompson, one of Britain’s worst mass murderers, or the Denmark Place fire, which remains the deadliest in post-war London, you are not alone. Even if it rings a distant bell after 35 years, you will not know the names of any of the victims, which have never been published in full. Here are three of them: Alejandro Vargas, Diana Coward, who was 18, and Alex Reid, who Paddy says went back inside to try to save a pregnant woman.

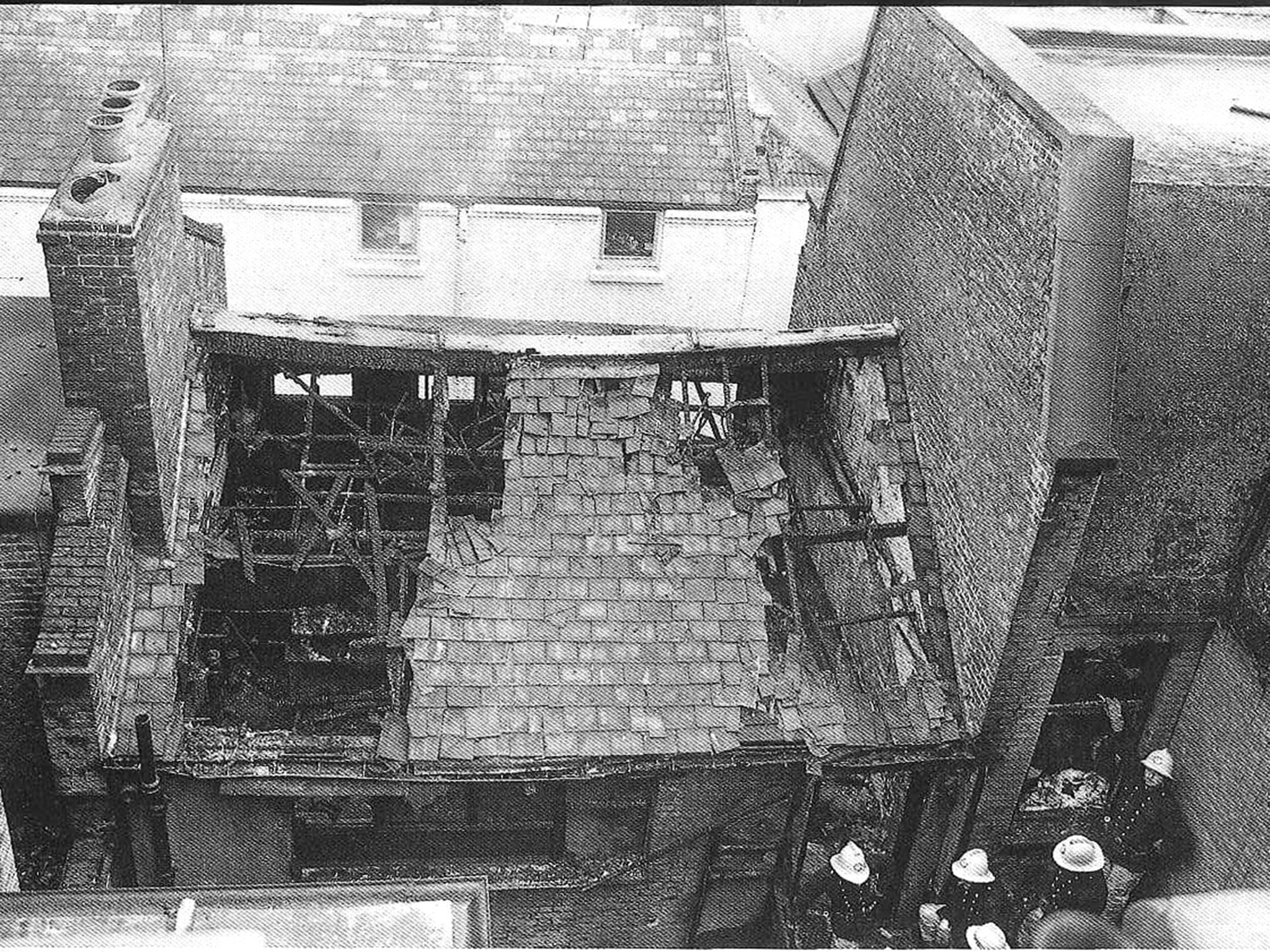

The fire was striking for its speed. Firemen found bodies slumped where they had been standing, some apparently still clutching glasses. Others tried to escape, clawing at walls and windows. Some broke through into the guitar shop behind the club, on Denmark Street, using electric guitars to smash through its front window. Experts took two months to identify all the victims, who came from eight countries.

But more striking than the fire itself is the speed at which it was forgotten. There were headlines the next day, once the bodies had been counted. “If it was arson, it could be the worst mass murder in British history,” The Sunday Times reported on its front page (it was, before Harold Shipman got caught). The Observer quoted a fireman: “I have seen worse fire damage, but I’ve never seen dead bodies packed together like that before.”

But then the coverage fizzled out. Today, online searches reveal only a few mentions. There is no Wikipedia page. Two or three little-known books devote a passage or two to the murders. As I will discover, even many of the victims’ families know very little about the fire. Seven years later, when 31 people died in the King’s Cross Underground fire, inquiries, services, documentaries and memorials followed. Princess Diana unveiled a plaque. At Denmark Place, there was no service. The only commemorative plaque in the area is devoted to the inventor of the diving helmet.

“Oh yeah, that’s great, the diving helmet,” Paddy says, sitting outside a chip shop on Charing Cross Road. She wears a blue Hackett polo shirt. The scars and tattoos on her arms map a bumpy life. “These people were murdered! When you walk round that corner, there are 37 souls walking up and down with you,” she says. “Why does nobody care?”

I learned about the Denmark Place fire in 2012, when I came across a book called London’s Disasters via a post at the Londonist website. The book’s author, John Withington, had worked at Thames Television in the early 1980s, but a planned film about Denmark Place came to nothing. “It is extraordinary how little attention it has attracted,” he says.

Matt Brown, who wrote the Londonist post, is a history buff. “I once gave a talk to a large group of historians,” he says. “A show of hands found that only a couple had any notion of the fire. And they specialised in London history.”

The fire’s causes and consequences partly explain the amnesia, Withington suggests. There were no terrorists nor a cartoonish serial killer. It was the era of Peter Sutcliffe, the Yorkshire Ripper, and Dennis Nilsen, the Muswell Hill murderer, who worked in a Job Centre yards away when the fire happened, and used to find victims in the area. The Denmark Place murderer was a hateful, stupid criminal with a match. In the harsh world of news, that was less of a story.

Thompson was arrested nine days later, while drinking at a club less than 200m from his own crime scene. He was tried at the Old Bailey the following May for just one murder, that of Archibald Campbell, 63. It was simpler that way. The trial clashed with the Ripper’s, drawing most reporters to the next-door court. The following year, Thompson’s life sentence earned a few column inches. When he died of lung cancer on the anniversary of the fire, in 2008, while handcuffed to a hospital bed, nobody noticed that either.

Moreover, there was never a public inquiry. The clubs were illegal. There seemed to be few lessons to learn, no institution to blame. This also means there is no official account. My search for details is a maze of dead ends. I contact museums and archives. The Colombian Embassy has no record. The Metropolitan Police’s archive contains only basic facts, which it only releases in response to a Freedom of Information request. An official at St Pancras Coroner’s Office, which held the inquests, tells me: “Even if we still had the files, which I very much doubt, you are not an interested person.”

When I return to the newspaper archives, other possible reasons for the vacuum emerge. The Sunday Times described “seedy clubs”. The Observer speculated about links to the Colombian drug trade or organised crime. The Daily Mail said drinking dens such as these appealed “not just to minority groups and tired prostitutes, but all kinds of folk intent on slumming”.

In its report of Thompson’s trial, the paper said that he had “felt at ease amongst the pimps, lesbian prostitutes, screeching homosexual queens, hash dealers and drooping addicts” of Denmark Place. No reporter ever interviewed a victim’s family.

Alex Reinhard was 10 months old when his father died at Denmark Place. Plutarco Alejandro Vargas Bernett was an architecture graduate from Bogota who had joined thousands of other Colombians for a new life in London. While working at a hotel, he met Doris, and they moved to her native Switzerland in 1978, a year before Alex was born. “People say he was tall and slim,” Alex, 36, says from his home near Zurich. “He liked music and he loved to dance. They said he was a very good dancer.”

In 1980, Reinhard’s parents visited London for a stag party, leaving him and his older sister with their grandmother. Vargas, who was 32, went on to Rodo’s, on Denmark Place, while Doris returned to a friend’s apartment. “My aunt and my cousins from Colombia said he always fell asleep at parties after a few drinks,” Alex says. “Maybe that happened that night. Others said that he helped other people to escape.”

As a teenager, Reinhard and his sister would search for information online, but find nothing. “In the world, so many horrible things happen and people forget very fast,” he says. He may never know exactly what happened to his father.

On Denmark Street, Paddy is still angry about the way nameless victims were shamed and forgotten. She thinks few if any of the Colombians downstairs were illegal immigrants, and says the mixed crowd upstairs were normal people having a good time. “They were human beings,” she adds. “They had mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters. They didn’t deserve to die.”

Families searching for answers typically now hit on the 2012 Londonist post. Its comments thread is extraordinary. In one exchange, a woman breaks it to a man called Jay that his girlfriend at the time, her sister Maria, died in the fire alongside two friends. Jay does not reply, nor respond to my messages, but the woman, Lorna Jeffers, does. “I really don’t have any information as I was only 10 at the time,” she writes. “As far as I know, the families never really got told much about what happened.”

The thread is also where I find Paddy, who commented early on. And it leads me to Matt Rendell, an author who had been researching the fire for years as part of a book he wants to write. He mentioned it in a 2011 book about salsa in Britain but, so far, no publisher wants the full story.

When Paddy reveals she knew many of the victims, several people ask her questions, including Alex Reid’s daughters, Nicola, who was five when he died, and Angela, who was months away from being born. Paddy tells them what a “lovely guy” he was. “You don’t know how amazing it is to hear this!” Nicola says. Angela, her stepsister adds: “I have been looking for information about what happened that night for years… if it wasn’t for the tiny bit about it in the paper when it happened, I would’ve been questioning whether it was true or not.”

Three years later, I can trace neither of Alex Reid’s daughters, but Rendell passes me an address for Reg Coward, who had contacted him. Diana Coward, who was 18, and from Greenwich in south-east London, was among the youngest victims, more than half of whom had British names. But her cousin Reg, who was 13 at the time, grew up not knowing what sort of fire she had died in. “Diana’s parents split up after that, and her mum drank herself to death,” he tells me. “It wasn’t something anyone talked about.”

When Coward, who is 48 and works as a delivery driver in West Sussex, stumbled on the Londonist post, he began to wonder. “I thought, blimey… it really jogged my memory about my cousin,” he says. He emailed Rendell, who had managed to get hold of a list of victims. Rendell told Coward, more than 30 years after the fire, that his cousin had been killed in an arson attack with 36 other people. “It’s really stirred me this last year or two,” Coward says. “It’s really sad that no one from that fire has ever been recognised.”

Pam Hopkins is Reg’s and Diana’s aunt. Diana was her bridesmaid. “How many people died in the fire,” she asks from her home near Basildon in Essex. I tell her. “Thirty seven!” she replies. “I had no idea it was that bad. I don’t think I ever read the papers.” The retired legal secretary, who is 66, remembers Diana as a pretty, determined girl who loved to sing. She had cut her blonde hair short as part of a gentle teenage rebellion. “We weren’t allowed to see her body,” Hopkins recalls. “They identified her from a piece of her bra that survived – she was wearing her mother’s bra – and her teeth.”

Reg Coward says Diana’s father, Albert, who is Pam’s brother, still can’t talk about the fire, although he now plans to broach the subject. Pam has always tried to keep her niece's memory alive. “I’ve got two children of my own and when that Paul Anka song ‘Diana’ came on when they were growing up, I’d tell them, because that was what she was named after. She’ll never be forgotten.”

No 18 Denmark Place is still visible from Charing Cross Road, and has been gutted ready for demolition. While evidence of the fire disappears, there is a campaign to preserve the area’s musical heritage. The Rolling Stones and the Sex Pistols, among others, started out here.

Henry Scott-Irvine, the leader the Save Tin Pan Alley campaign, says that, where it is remembered, the fire is lumped in with anecdotes about the area’s insalubrious past to justify its gentrification. “It’s like the push to get rid of the gin houses of Hogarthian London, which these buildings replaced,” he says.

Yet no one would deny the area’s chequered past. The Great Plague of London started in squalid housing here. Subsequent slums inspired Dickens, and by 1980, crime and vice was still common. “There were all kinds of hoods, and syringes being thrown over the wall into our courtyard,” says Glen Matlock, the original bassist with the Sex Pistols (before Sid Vicious). He lived in a house behind No 6 Denmark Street in the late 1970s. It’s now the back office for a guitar shop, but graffiti that Johnny Rotten scrawled on the walls still survives.

“I was in a barber’s on the street once and the bloke was finishing off with a cut-throat razor,” says Matlock, who only vaguely remembers the fire. “I could see in the mirror this stocky bloke in an expensive suit in the doorway. The barber went, ‘I’m not paying you again’, and the guy unbuttoned his jacket. He had a gun in a shoulder holster. The bloke was shaking with the razor and went to finish with me. I said, ‘don’t worry mate, pay him first’.”

Such anecdotes are rife, but there is a sense that the street wanted to forget the murders of 1980. Afterwards, 18 Denmark Place was restored and had many uses. On the other side of the wall, at 22 Denmark Street, Guy Katsav, an Israeli-born producer, now manages the basement music studios where The Beatles, David Bowie, and Jimi Hendrix wrote songs. The day I visit, he’s busy tidying up for Dizzee Rascal, who’s due in later. Katsav is horrified when I tell him about the fire next door.

Upstairs, Andy Cooper’s uncle used to run Rhodes Music, the shop people used as an escape route. “He didn’t talk about it,” says Cooper, who went on to run his own shop. “Only locals would remember now and there aren’t many of them left. And maybe they didn’t want to remember anyway.”

But many people do remember, and want some sort of memorial to be added to the area. Camden Council tell me that it would only consider a formal application from victims’ families, who would also have to pay for a memorial. So I contact the developer who is transforming the area.

Laurence Kirschel, a former business partner of the late Soho porn and property baron Paul Raymond, bought acres of land here in 1996. He is now worth an estimated £320m, and his St Giles Circus project should make him richer still. In his insanely opulent, unmarked offices on Soho Square, his right hand man Richard Metcalfe shows off an architect’s model. It stands in the corner of a boardroom, below a window which offers a distant view of Denmark Place itself.

The alley is due to be reopened in 2018. No 18 and its row of five houses will be rebuilt in the same style, and serve as the entrance to a new underground music venue. I ask Metcalfe if Kirschel would consider putting up a plaque. The men were only vaguely aware of the fire, but after I relay the views of Paddy, the Cowards and Alex Reinhard, who also want a memorial, Kirschel agrees to include one outside 18 Denmark Street. “The wording I think should come from the families,” Metcalfe says.

What would Pam Hopkins, Diana’s aunt, like the plaque to say? “It’s very hard, isn’t it,” she says. “But I think it should say something about those who were lost unnecessarily.” Paddy proposes a line in a text message: “In memory of the 37 innocent people who died in an arson attack here on 16 August 1980, and who are always in our hearts and minds.”

Paddy still goes out in Soho and always strolls up to Denmark Place, following the steps she did not take 35 years ago. She isn’t religious, “But when I’m here I look up and hope that Alex and the rest of them are resting in peace,” she says. “And then I look for someone – anyone – and I tell them what happened.”

Click here to view the list of victims or contact the author: ind.pn/denmarkplace

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks