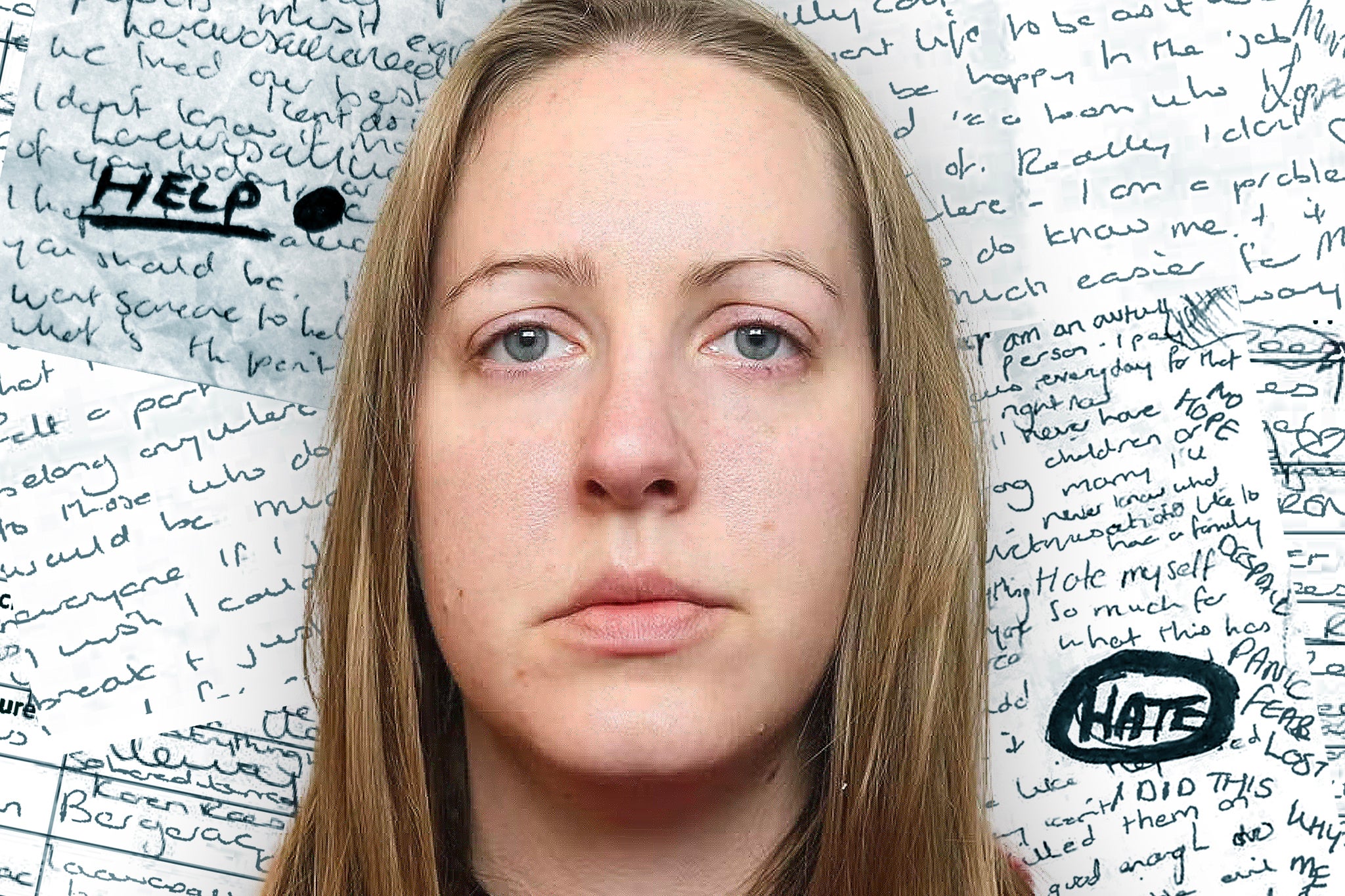

Is Lucy Letby innocent? I’m a miscarriage of justice investigator – and here’s what I think...

As Sir David Davis adds to the chorus of voices raising concerns about the conviction of ‘killer nurse’ Lucy Letby, former commissioner at the Criminal Cases Review Commission, David James Smith, looks at how seriously they should be taken

A telling phrase rang out from the latest trial of Lucy Letby. The prosecutor claimed that she had been caught “virtually red-handed” attempting to murder Baby K, by her colleague Dr Ravi Jayaram. Jayaram had come upon Letby standing over and watching the baby, it was said, as the baby “desaturated”, losing oxygen.

As the baby’s breathing tube had reportedly been dislodged and the alarm had apparently not sounded, the inference was that Letby had removed the tube herself and paused the alarm, intending the baby would die (as Baby K eventually did three days later). But this inference depended, almost entirely, on the reliability of Dr Jayaram’s version of events, about which he was challenged in cross-examination. Letby denied doing any harm.

Having heard their opposing accounts, a unanimous jury took just over three hours to find Letby guilty of the attempted murder of Baby K. The “red-handed” incident was no longer an inference; it was a fact. One that the judge could and did assert in his sentencing remarks, before condemning Letby to a 15th whole life order for her crimes.

Letby had refused to appear for sentencing at her earlier trial, but for the retrial of this charge, the 34-year-old stood in the dock of Manchester Crown Court. As she left to resume her jail term, she paused to say quietly, back into the court: “I’m innocent”. A statement that must have added to the distress of the family of Baby K, who described having to endure a “long, torturous (sic) and emotional journey – twice”.

During my time in office as a commissioner at the Criminal Cases Review Commission – the body responsible for investigating alleged wrongful convictions and referring cases for a new appeal where there is a real possibility of success – I encountered many safe verdicts that had been built on circumstantial evidence.

We cannot know whether Letby is innocent. Only Letby herself knows that. But we can say that she was never caught “red-handed”; she was not seen committing those acts and there is still no definitive forensic evidence linking her to them. I am not a lawyer, but every criminal practitioner knows that “indirect” evidence, especially where it exists in multiple strands, can be powerful and compelling evidence of guilt, underscored by the unlikelihood of coincidence.

In another contested case from 20 years ago, a male nurse, Benjamin Geen was convicted of killing two patients and harming others by injecting them with overdoses of drugs. He was not caught in the act, but on his arrest, as he arrived at the hospital for work, he was found with a syringe in his fleece pocket which contained one of the drugs (and traces of others) that he was alleged to have used. Although he and his supporters continue to claim he is innocent, that syringe is a significant obstacle to his chances of a successful new appeal.

However, circumstantial evidence also has the capacity to mislead juries into reaching the wrong conclusion, perhaps never more so than when it appears plentiful, and in almost complete absence of direct evidence.

At first glance, the case against Letby seems overwhelming. She pleaded not guilty to 22 charges of murder and attempted murder, arising from the deaths and collapses of an abnormally high number of newborn babies in the neonatal unit of the Countess of Chester Hospital.

The incidents in question occurred between June 2015 and June 2016, while Letby, then in her mid-20s, was working there as a neonatal nurse. According to an analysis of the staff shift patterns, she was the one person present at every event.

Letby was first arrested in 2018 and the trial took a painstaking 10 months, from October 2022 until August last year. She was alleged to have injected the babies in her care with air, or forced air into them through tubes leading to fatal air embolism, and also caused them internal bleeding and trauma. She is also alleged to have poisoned two with insulin and overfed two others with milk. The trial heard from her colleagues and from medical experts, led by Dr Dewi Evans, who attested to Letby’s methods.

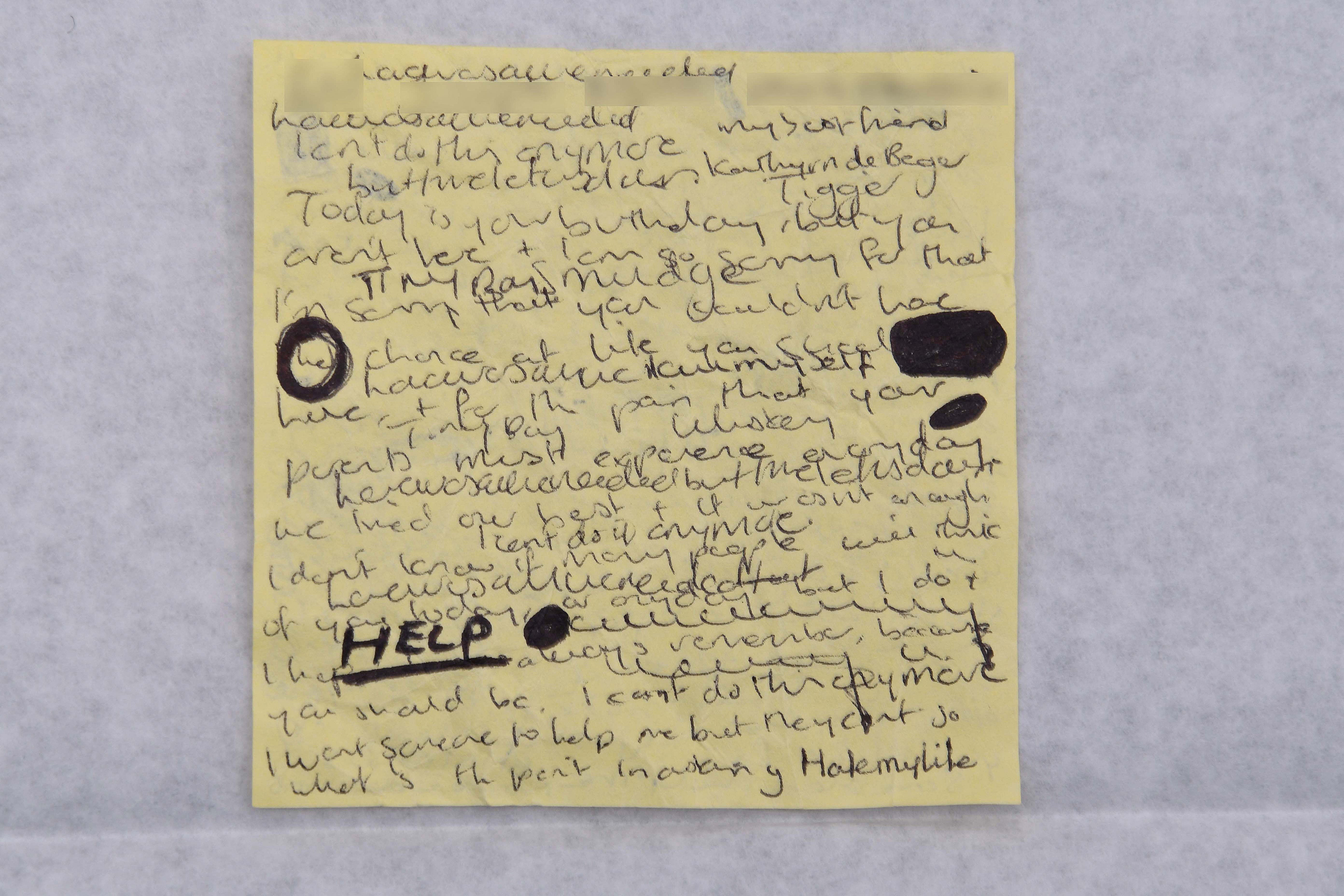

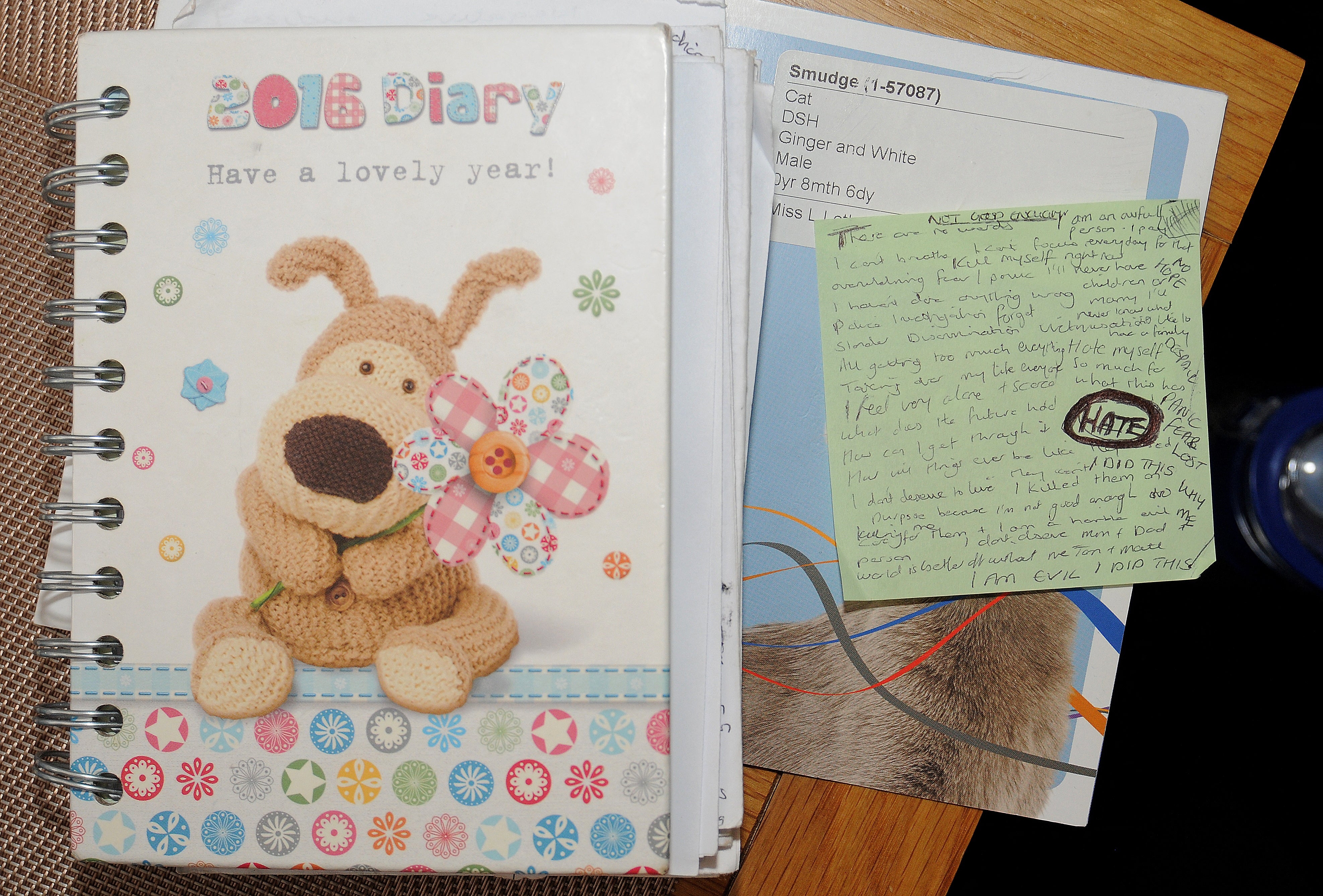

There was evidence too of her morbid fascination with her crimes, searching families on Facebook, hoarding confidential documents about the cases at home and revealing her own thoughts in scrawled notes which include the now notorious admission, “I am evil, I did this”.

The jury returned seven guilty verdicts on murder and seven guilty verdicts on attempted murder. They acquitted her on two counts of attempted murder and were unable to agree verdicts on six further counts of attempted murder, including the case of Baby K.

For her crimes, Letby was sentenced to 14 whole life orders. The trial judge, Mr Justice Goss, told her she had acted “in a way that was completely contrary to the normal human instincts of nurturing and caring for babies and in gross breach of the trust that all citizens place in those who work in the medical and caring professions.”

Letby, Goss said, claimed that she never did anything that was meant to hurt a baby and only ever did her best to care for them. “That was but one of the many lies you were found to have told in this case” she was told. Doctors had to “think the unthinkable” when they became suspicious of her.

The verdict was met with an avalanche of publicity; Cheshire Police released their own in-house documentary revealing how they had successfully investigated Britain’s worst serial killer of babies. And with the reporting came many reminders of the double tragedy faced by families whose babies had died or suffered serious harm – only to later be told that one of the people caring for them had been responsible.

I was not alone, however, in finding the case perplexing. While the Crown did not have to explain why Letby had committed the crimes, there was no indication whatsoever as to motive, nothing to suggest any profound psychological flaw that such crimes might require.

As painful as it may be for the families of the babies who died or suffered harm, the ball is in Letby’s court to decide to make the next move

There was testimony, in fact, that Letby was a diligent, compassionate and hard-working nurse. Her parents supported her. So did many of her friends. Much was made of her apparent confession, “I am evil, I did this” scrawled on scraps of paper.

On first look, it certainly looked like evidence of a troubled mind, but on closer inspection others have since suggested, this could easily be an expression of a deterioration of mental health and self-loathing at the association with the deaths of the babies and the increasing suspicions of doctors who worked with her.

A growing body of people – statisticians, scientists and doctors among them – were starting to openly question the evidence on social media and elsewhere. They were not associated with or encouraged by Lucy Letby or her lawyers. In fact, many were blatantly critical of Letby’s defence team, which had been led by Ben Myers KC with a local solicitor from Chester, Richard Thomas.

As the Crown Prosecution Service promptly announced its intention to put Letby through a retrial for the attempted murder count of Baby K and with proceedings now active, reporting restrictions were swiftly put in place. No mainstream broadcast or print media in the UK would, rightly, have dared to breach the restrictions and interrogate the concerns around her conviction. To do so would mean they would face proceedings for contempt of court.

However, in one podcast serial, We Need To Talk About Lucy Letby, a statistician Peter Elston and Michael McConville, a retired paediatrician, tore into the case, with detailed arguments about the inadequacies of the medical evidence and concerns about the administration of the hospital and its neonatal unit, especially the inadequate levels of staff and training. Questions were raised about the key statistical element of the case: the graph that showed Letby’s presence at all the events.

Dr Dewi Evans was not just the Crown’s trial expert, he was also an adviser in the police investigation and reviewed 60 cases of baby deaths and collapses (nearly three times the number charged) for assessments of foul play. It was suggested that the Crown had repeatedly, misleadingly referred to the babies as stable when in fact, by definition, they were anything but, because they were in the special care unit in the first place.

Very sadly, some premature babies do die or suffer collapses quite naturally, or sometimes because of “sub-optimal” care. A previous review into the unit had found it was short of nursing staff and consultants were spread thinly between the paediatric ward and the neonatal unit. Junior staff reported feeling like they couldn’t call on them and, consequently, the unit was often left in the care of less experienced doctors working in a very stressful environment.

How would the graph look if it showed the shift patterns of all the cases and not just those that had been cherry-picked by the prosecution? Clearly, Letby was not on shift for them all, so the graph, it is claimed by campaigners, was misleading. There were many other incidents in the neonatal ward for which she was not present, and so could not apparently be blamed.

Much was made of the fact that the number of deaths fell once Letby was removed from neonatal duty, but around this time hospital management had also downgraded the unit, so that it stopped taking the most premature babies with the highest risk of mortality.

Then there was the question of the causes of death and collapse, attributed to Letby, which appeared at times to be speculative, and had passed unnoticed in the initial post-mortems and reviews that followed the incidents. An enduring puzzle of the main trial was why the defence had not called any expert evidence itself, to rebut the claims of the prosecution and offer alternate explanations for the deaths.

We learned from the recent failed appeal in the case, that the defence had instructed experts but never called them. Ben Myers, on Letby’s behalf, had gone in hard on Evans during cross-examination and there had been some spiky exchanges as Evans was accused of being inconsistent and going for whatever mechanism might fit his explanation for Letby’s involvement in the incidents.

He claimed, for example, that various descriptions of different types of skin discolouration were consistent with air embolism. Ruling out other causes of death, he seemed to say, left air embolism as the only answer. But was it? Testimonies from another expert who wasn’t called when they could have been claimed not.

Letby and her lawyers have not engaged so far with the media. They have, to the best of my knowledge, declined all offers of help from the various circling experts. In May, a whopping 13,000-word New Yorker article was published – while the reporting restrictions were still in place in the UK – which raised further questions about the varieties of circumstantial evidence in the prosecution case.

Now, with the retrial over and the restrictions no longer in place, a chorus of concern is growing louder. More publications are reporting the detailed worries of medical professionals and statisticians. Although it is not yet a concerted campaign, there is said to be a body of senior politicians who are concerned about the safety of Letby’s convictions and about the way that medical and statistical evidence has been presented in this case and others.

So where does this leave us? It had been suggested to me by a reliable source that Letby would be charged with further counts of murder but since that has yet to happen, either I was misinformed or the CPS has changed its mind or is still considering its position as to whether a further trial would serve the interests of justice.

Letby can seek leave to appeal the latest attempted murder conviction – we won’t know unless or until the case is listed for hearing. But a fresh appeal on the other 14 convictions lies solely with the Criminal Cases Review Commission.

The CCRC is currently under scrutiny because of its role in the prolonged injustice faced by Andrew Malkinson (who spent 17 years in prison for a rape he did not commit). Two reviews of the CCRC's role in the Malkinson case are imminent.

Those circumstances may focus their mind on doing their best work, and the Commission has dealt with complex medical cases in the past. It can instruct experts, review evidence, and, perhaps importantly, invite trial counsel to explain their tactics and decision-making – a necessity for any future chance of appeal. No one should be under any illusion that this is a quick process – it could take a year, or years.

As the Commission can only accept applications from the applicant or their instructed lawyers, despite a number of experts who now feel the case is flawed and are frustrated at her lawyers’ refusal to involve them, the CCRC cannot accept applications from outsiders. It is now up to Letby to choose her representation, and all the signs are that she is content with her current legal team.

As painful as it may be for the families of the babies who died or suffered harm, the ball is in Letby’s court to decide to make the next move, which would mean the case is revisited with a rigorous inquiry and expertise. But, whatever they decide and however difficult it is for the grieving families, it is evident the voices asking them to do so shows no sign of quieting down anytime soon.