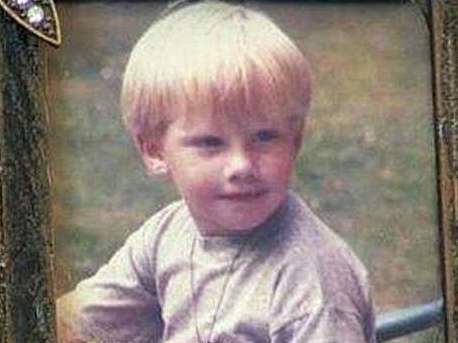

Boy, 7, who contracted Aids in contaminated blood scandal’s last words shared by family

Colin Smith contracted Aids after receiving contaminated blood at just ten-months-old while being treated for haemophilia

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The family of a seven-year-old boy who died as a result of the contaminated blood scandal has shared his last heartbreaking words 34 years on.

Colin Smith contracted Aids after receiving contaminated blood at just ten months old while being treated for haemophilia.

The young boy was infected with HIV and hepatitis C in August 1983 after being given blood products imported from the US. He died in 1990, aged seven.

Speaking to the BBC, his family shared his final words: “I can’t see daddy”.

His family are speaking out upon a new BBC investigation which found the doctor who infected his blood, Prof Arthur Bloom, broke his own rules to do so.

Just three months before Colin was infected, Prof Bloom’s department had written internal NHS guidelines discouraging the use of imported blood treatments on children due to infection risks.

“This wasn’t an accident,” Colin’s father told the broadcaster. “It could have been avoided.”

Between 1970 and the early 1990s, an estimated 30,000 people in the UK were given blood transfusions infected with hepatitis C or HIV. At least 2,400 people died as a result, while more than 4,000 survivors continue to suffer the effects of the catastrophic error.

In 2022 the Infected Blood Inquiry was established to investigate how the transfusions were allowed to take place. At the same time, the government announced that victims would receive £100,000 in compensation. However, Rishi Sunak has since been criticised for the speed of the government’s response and delays in payments.

ITV is to follow the success of Mr Bates Vs The Post Office with a drama exploring the contaminated blood scandal – widely recognised as among the darkest episodes in NHS history.

The show will examine what doctors, politicians and pharmaceutical companies knew about the risk, and the scandal that has endured for more than 50 years.

Speaking about his son’s infection, Colin’s father, also called Colin, told the BBC: “They were playing Russian roulette with people’s lives, and they miscalculated and killed thousands.”

Colin’s mother, Janet, described how the family were told about his diagnosis while standing in a busy hospital corridor.

“Colin was lying in bed, not well at all, and Prof Bloom stops in the corridor and just said ‘he’s HIV’,” she said.

“We were never taken to a room, we were told in the middle of the corridor, parents running after their kids, little kiddies running past us, and I can remember getting really upset but I don’t know why because it was never explained that it was a death sentence.”

The family described how they were ostracised by their local community following their son’s diagnosis.

“We were known as the Aids family,” Janet told the BBC.

“We’d have phone calls 12, one o’clock in the morning. ‘How can you let him sleep with his brothers? He should be locked up, he should be put on an island’... he was three.”

“It got out of hand,” said Colin senior. “One day we got up and ‘Aids dead’ was written right across the side of the house [in] black paint.”

The bereaved parents believed their son was given new heat-treated blood product Factor VIII which, it was hoped, would kill viruses like HIV and hepatitis.

“He just happened to be diagnosed with haemophilia at the same time these trials were starting up - the next thing you know he’s got HIV,” Janet said.

The NHS blood services began routinely screening donations for HIV in 1985 and screening for hepatitis C in 1991.

The infected blood inquiry is expected to publish its report on 20 May.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments