Up to 140,000 children left at risk of neglect and abuse as cash-strapped councils struggle to cope, figures show

'When the evidence tells you one thing [about a vulnerable child] but the budgets tell you a different thing, you go with the budget rather than the evidence'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As many as 140,000 vulnerable children at risk of abuse and neglect might not be getting help because cash-strapped local authorities have been forced to shrink or abandon family support, according to new figures.

Thousands of young people in England who have been referred to children’s social care services by teachers, police or health professionals because of concerns over domestic violence, parental mental health, neglect and physical abuse are being left without support because councils do not have the capacity to intervene.

Figures obtained by charity Action for Children through Freedom of Information requests to 152 local authorities revealed that in 2015-16, 184,500 children’s needs assessments were closed as “no further action” as they did not meet the threshold for statutory services.

Of these, just one in four families were given help such as the use of children’s centres or domestic violence programmes, leaving an estimated 140,000 children without support.

The charity warned that children coming to school hungry and dirty or showing signs of domestic abuse or parental substance misuse were not getting help when they were referred to authorities, and therefore opportunities to “act early” and protect youngsters from further harm were being missed.

Tony Hawkhead, chief executive of Action for Children, told The Independent: “It could be that teachers are noticing they’re hungry at school, it could be signs of domestic abuse or drug use in the home.

“They are all serious but in the definition of the threshold they aren’t seen to be sufficiently in need, meaning they don’t get help. But there is every prospect they will reappear not long after, possibly with needs becoming more difficult and acute and more expensive to resolve.

“All the evidence we have shows that the earlier we can provide support, the more valuable the help will be and the better it is for the family and wider society.”

It comes after The Independent revealed last week that council leaders warned that funding cuts had pushed children’s social services to “breaking point”, with action only being taken to protect youngsters once they are at imminent risk of harm.

Analysis of figures by the Local Government Association (LGA) revealed that three-quarters of English councils exceeded their budgets for children’s services last year, totalling a £605m overspend, while the number of young people subject to child protection enquires increased by 140 per cent – to 170,000 – in the past decade.

Meanwhile, universal family support services have been forced to close due to cuts, with children’s centres shutting at a rate of six per month since January 2010.

Central government funding for Sure Start children’s centres, teenage pregnancy services, short breaks for families of disabled children and other types of family support services is predicted to reduce by 71 per cent in the 10 years from 2010 to 2020.

Local authority managers said that while evidence shows investing in early intervention services is important in keeping children safe, budget cuts mean they are increasingly having to “stick a plaster” on problems, leaving them “unable to completely recover”.

Speaking to Action for Children, one local authority manager said: “The jury is still out for children’s centres. We say we’re intelligence led and evidence based – but when the evidence tells you one thing but the budgets tell you a different thing you go with the budget rather than the evidence.”

Another said: “If a parent is still consumed by heroin use day-in day-out, or subject to bad mental health, or offending behaviour ... ‘you stick a plaster on it’. And while you continue to just stick a plaster on it, actually it’s not going to completely recover.”

Responding to Action for Children’s findings, Richard Watts, chair of the LGA’s Children and Young People Board, said councils were doing “everything they can” to respond to “significant underfunding” in children’s social care.

“As a result of funding cuts and huge increases in demand for services, the reality is that services for the care and protection of vulnerable children are now, in many areas, being pushed to breaking point,” he said.

“Councils are doing everything they can to respond to the significant under-funding in children’s social care, including protecting budgets, reducing costs where they can and finding new ways of working.

“However, they are at the point where there are very few savings left to find without having a real and lasting impact upon crucial services that many children and families across the country desperately rely on.”

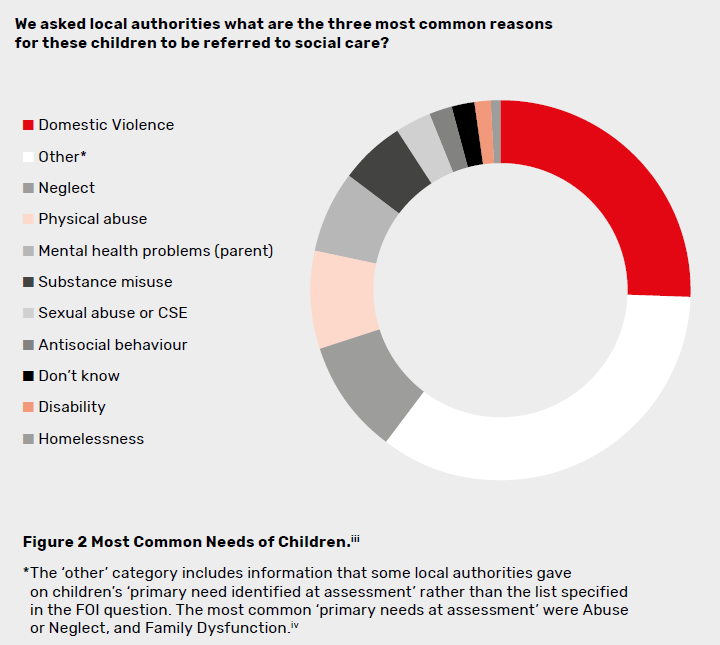

According to the report by Action for Children, the most common reason for referral was domestic violence, followed by neglect, physical abuse, mental health of parent and substance misuse.

It comes at a time when hardship is hitting families across England hard, with figures showing that 30 per cent of children are now living in poverty, while an estimated 189,119 live with at least one alcohol-dependent adult and one in five has experienced domestic abuse.

Mr Hawkhead urged the Government to “strengthen the legal framework” around local help so social services were clear on how to help families early, adding: “They recognise that there is a funding gap, but this cannot be taken from crisis support.

“Unless we help local authorities it’s going to continue to be a revolving door of children being referred for serious needs.”

A Department for Education spokesperson said: “Across Government, we are taking action to support vulnerable children by reforming social care services and better protecting victims of domestic violence and abuse.

“Councils will receive more than £200bn for local services up to 2020 and spent nearly £8bn last year on children’s social care but we want to help them do even more.

“Our £200m Innovation programme is helping councils develop new and better ways of delivering these services – this includes projects targeting children who have been referred and assessed multiple times without receiving support.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments