British chicken sexing in crisis: experts needed to spot a 'very, very small' difference

UK poultry farms have shortage of specialist workers. Oscar Quine finds out what’s involved

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The British chicken sexing industry is in crisis. In hatcheries up and down the country, golden day-old chicks cascade down conveyor belts waiting to have their gender established, so they can be assigned to lives as roosters or egg-layers.

But, with no new recruits since 2012 – and the value of poultry exports increasing at a rate of five per cent a year – the UK’s 29 qualified professionals are struggling to keep up.

In the interests of helping sustain a burgeoning British industry, I was tasked with arranging a masterclass in how to sex a chick. If the nation realises what is involved (not to mention the £40,000 starting salary), this crisis could be overcome.

But it quickly transpires that arranging said demonstration is easier said than done.

“We have the toughest biosecurity in the world,” explains a representative from the British Poultry Council. “You can thank Edwina Currie.” To get inside a hatchery, I would need, at the very least, a salmonella test – the results of which will take two weeks. Instead it is suggested we conduct the masterclass via webcam. But it soon becomes apparent this won’t fly either – any electronic equipment would need to be fumigated.

And if a chick is removed from the hatchery, it cannot go back in. Chances are, they’d have to kill it.

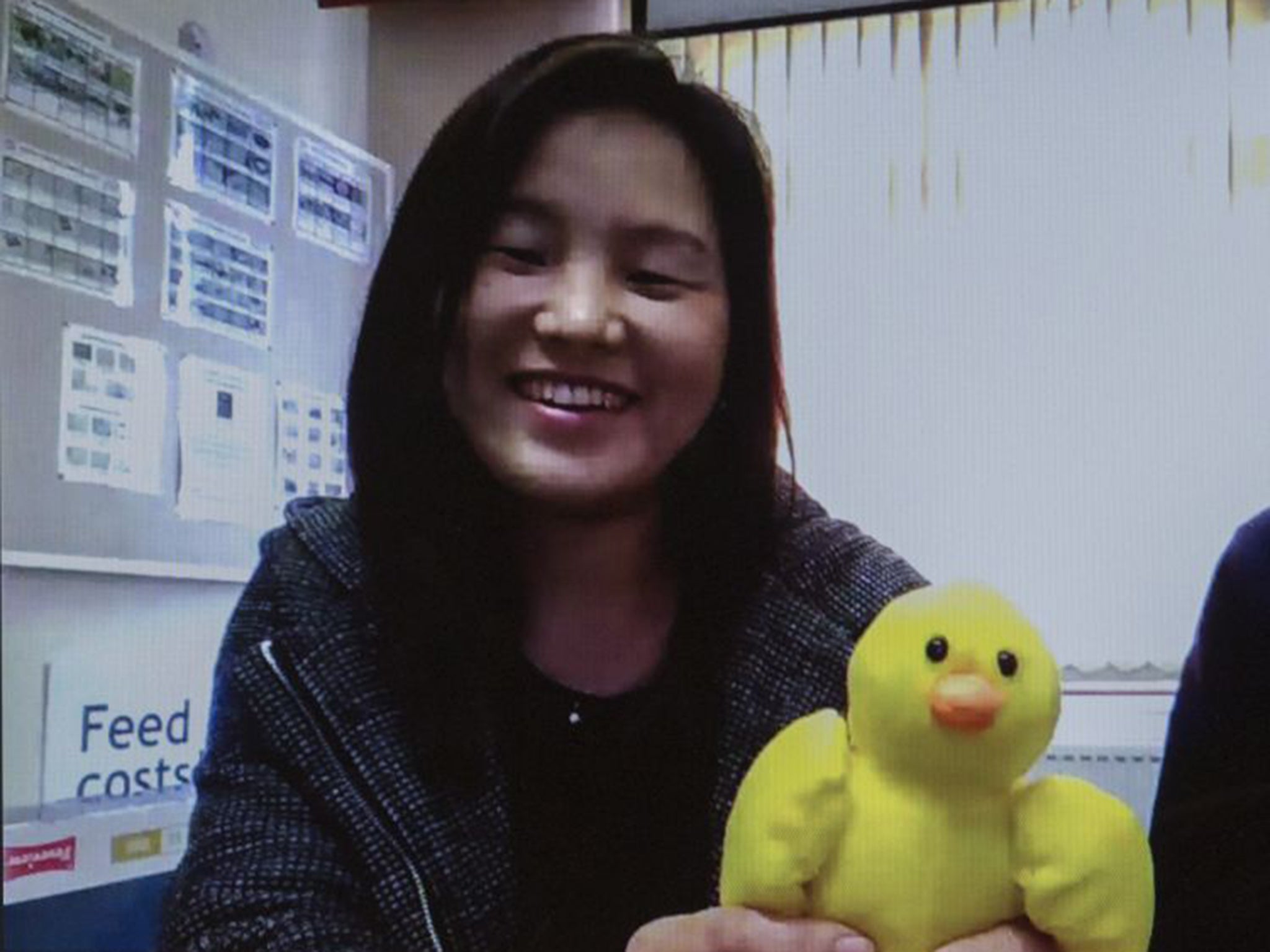

So it is that I find myself at my desk at 3pm on Monday afternoon staring at a glitchy video stream of Youngsim Jung Dixon, star chicken-sexer at poultry breeders Cobb Europe, and John Vincent, head of the company’s European production.

They are in a windowless office somewhere in Norfolk, according to Mr Vincent. Ms Jung Dixon is holding up a soft-toy chick with bulging eyes, purchased hastily from a nearby garden centre. Explaining that the stuffed toy is too big – more the size of a three-week-old chick – Ms Jung Dixon picks up a smaller plastic model, flips it over and demonstrates how she would use her two thumbs to open its vent.

“The mark is remarkably very, very small, less than 0.1mm,” she says. “It’s a very small difference to look for. Males look more three-dimensional and females look flat. In about 10 per cent of chicks, it’s very similar but you have to find out which is which.”

The key to this, she says, is practice. Sexers sit in a darkened room, under individual spotlights, hunched over a conveyor belt for shifts that can last up to 13 hours.

A first-class sexer like Jung Dixon can sort 1,200 chicks an hour, always with the utmost delicacy in order not to damage the chick.

“I could sex a chick for you but it probably wouldn’t be alive at the end of it,” says Vincent. “People like Youngsim are so uniquely different from the normal teams. They’ve just got an ability. I don’t know whether it is God-given or trained but it is different. It isn’t for everybody, that’s for sure.”

This combination of dexterity and unwavering concentration seems in short supply in the UK. Sexers are predominantly recruited come from Japan – where the method was developed – and South Korea. The British industry is now calling on the Home Office to help avert an acute crisis – and unfulfilled export contracts – by relaxing immigration restrictions on the profession.

Andrew Large, chief executive of the British Poultry Council said: “The industry welcomes people whatever their background to train as a chicken sexer. However, the unique skillset and high levels of accuracy required means we will continue to call for this job to be included on the Home Office shortage occupation list.”

But there is also hope closer to home. Andy Moss, 65, from Stratford-upon-Avon has been sexing chickens since the age of 18. As well as being Secretary of the Association of British Chick Sexers, he is a partner in the Southwest Chicken Sexing Service. He is currently training five sexers – and says he received 75 emails from prospective trainees after the shortage first hit the news last week.

“A lot of them don’t have a clue what’s involved,” he says, confirming that focus is key. Has he ever, in his forty-odd years in the game, got a little bored? “No, if you concentrate, hours just fly by.

“You can’t look out the window. It’s not like anything else.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments