British army’s atomic bomb guinea pigs still fighting for justice 70 years on

They are known as the ‘atomic veterans’ – men who served in the 1950s and were handed cloths to cover their eyes as the army tested the effects of a nuclear blast on them. Decades on, Joe Shute hears how they and their children have suffered years of health complications and why this could be another scandal similar in scale to the Post Office and infected blood cases...

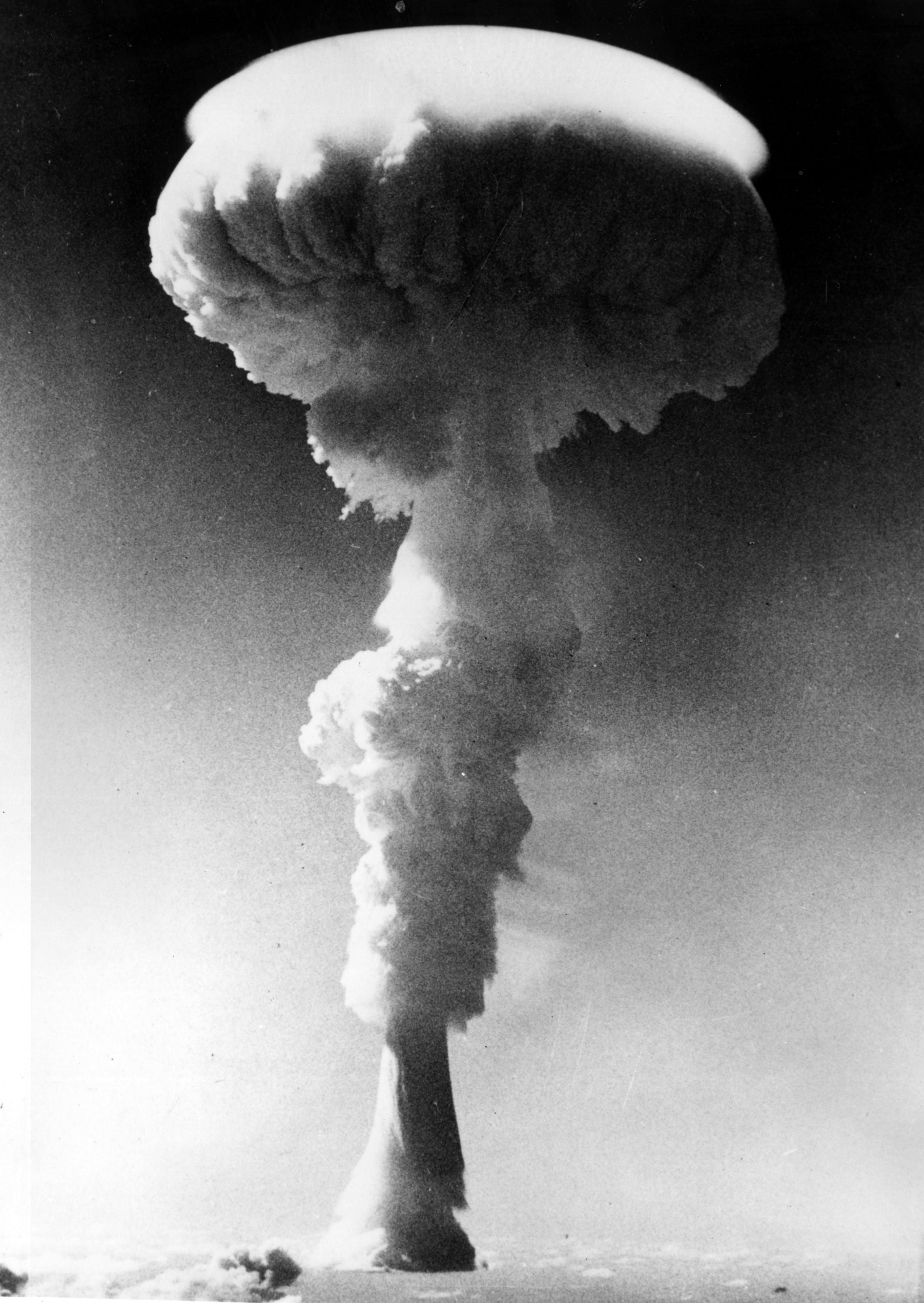

The way John Morris tells it, there are four phases to watching a nuclear bomb explode. The first is the light, so bright that when he covered his eyes with his hands they were transparent almost to the bone. Then an intense heat which scorched palm trees, melted the windscreen wipers off army trucks and left his back feeling as if it was on fire.

Next came the blast, which blew him and those around him clean off their feet. Finally, from the detonation site 20 miles away in the Pacific Ocean rose a twisting mushroom cloud like a toxic fountain melting the sky.

“It was a beautiful but terrifying thing to see,” the now 87-year-old says. “It was so intense and so severe. The experience lives with you forever.”

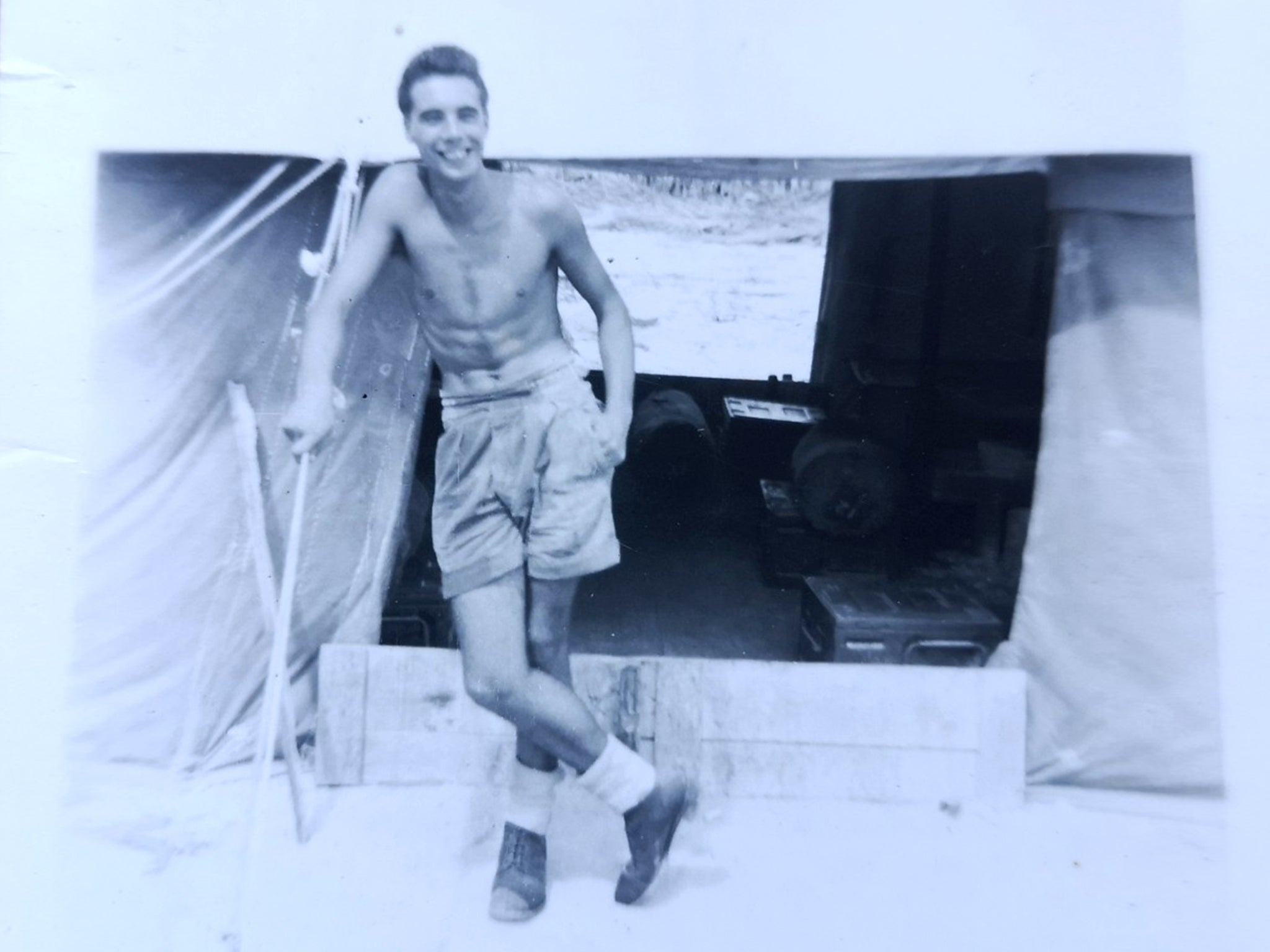

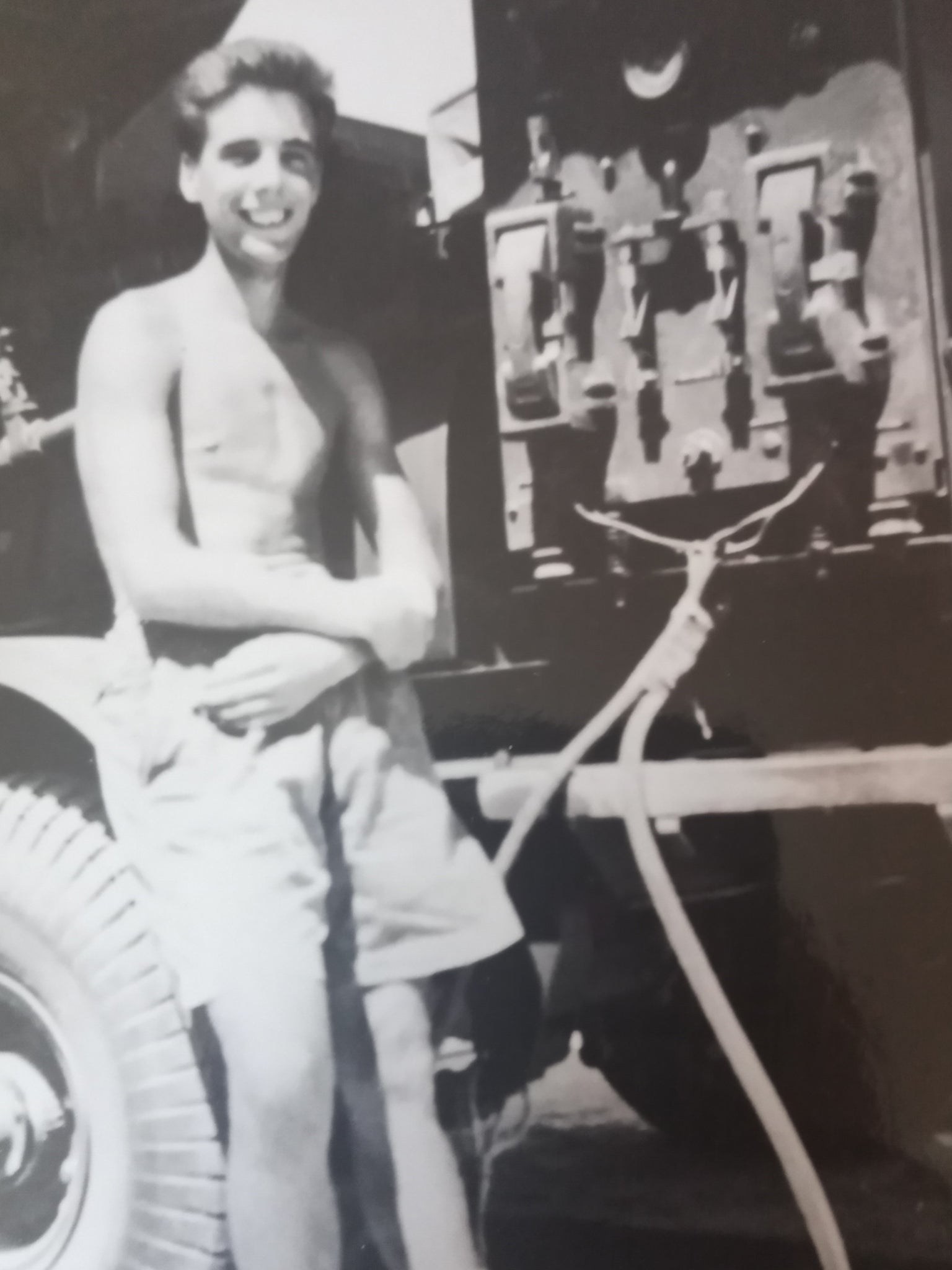

Morris was 18 and working in a paper mill near Bolton when he was conscripted into national service in 1956. After a short training stint in Portsmouth, he was posted to Christmas Island with the Royal Army Ordnance Corps.

He presumed he was going to help construct a runway and initially couldn’t believe his luck, washing up on a paradise island with coral seas and swaying palms. But in fact, he would be unwittingly part of Britain’s Cold War nuclear testing programme in the South Pacific – the fallout from which still haunts him and his family to this day.

In total, four detonations took place during John Morris’s time on Christmas Island in an exercise codenamed Operation Grapple. Even when bombs were dropped hundreds of miles away, sea waters would still rise and flood the tiny atoll. When the fourth and final bomb was dropped, Morris was tasked with watching alongside around 1,000 other men.

The only safety protocols were that they were told to sit with their backs to the blast, handed army-issue sunglasses and instructed to use a cloth to cover their eyes. Most – including John – were dressed in shorts.

In 1958 he left the army and came home, marrying his wife, Betty (she later died after 40 years together). They had a young son, Steven, who was found dead in his cot aged just four months old. Initially, the couple were arrested on suspicion of murder, but a coroner later ruled pneumonia as the cause of death.

Morris, who had three further children, says he has struggled for decades to obtain copies of his son's autopsy report after several attempts to the local coroner were rebuffed. Eventually, he only secured it through a freedom of information request two years ago.

“That suggested the lungs on his body hadn’t formed correctly,” he says. “But we didn’t know that at the time.”

Soon after his son’s death, John started struggling with his own health complications. An extremely fit young man prior to his army service, he was diagnosed with pernicious anaemia, an autoimmune condition he has received injections to manage for the past 60 years.

Later after suffering a broken arm, he was told by doctors it was taking months longer to heal than was considered normal – and nobody could explain why. He says he doesn’t know of anyone he served with who is still alive. “They’ve all died from some sort of cancer,” he says. “I use the word ‘unnaturally’.”

An estimated 22,000 service personnel took part in Britain’s nuclear testing programme between 1952 and 1967. A study conducted in 1999 on the health outcomes of 2,500 servicemen, found 30 per cent had already died (mostly in their fifties) of which two-thirds were the result of cancers that have been linked to radiation poisoning. Other health problems including infertility, skin defects and musculoskeletal conditions were also recorded – and in their children and grandchildren too.

However, a separate long-term study of a group of veterans commissioned by the Ministry of Defence (MoD) and involving a research team at the National Radiological Protection Board, has found overall the rates of cancer and other mortalities were broadly similar to a control group (although higher rates of leukaemia were detected among the veterans).

Other countries involved in nuclear testing, including the US, Canada, France and Russia, have agreed to compensation payouts. To date, the US government alone has paid out more than $2bn in claims. Britain, however, refuses to do so, which has led to claims of an institutional cover-up over decades, similar in scale to the Post Office and infected blood scandals.

In 2012, the Supreme Court ruled against a group of around 1,000 veterans seeking compensation from the MoD (which denies liability). More recently, surviving veterans (of whom around 1,500 remain) have been calling for the MoD to release their medical records during their time in the forces, including any blood tests conducted, and calling for a formal inquiry.

The MoD, meanwhile, has long argued that veterans can access their medical records on request. Veterans can apply to the MoD via a process known as a “subject access request” while their families can submit freedom of information requests – although many struggle with what remains an opaque process.

Fresh political momentum could break this stalemate. The mayor of Greater Manchester, Andy Burnham, who attended an event to support the veterans at this week’s Labour conference, has backed a public inquiry.

In opposition, Sir Keir Starmer met with the nuclear test veterans while last year, his deputy Angela Rayner pledged her support. Particular hope rests on the new Hillsborough Law announced this week, which will force public bodies to cooperate with investigations into major disasters or face potential criminal sanctions.

Given the average age of the surviving veterans is 87, Alan Owen, co-founder of the campaign group Labrats, whose father participated in Operation Domenic on Christmas Island in 1962, says an inquiry must take place as soon as possible. “These guys want an inquiry to put this to bed once and for all,” he says.

Owen’s father died of a heart attack aged 52 (the third he had suffered). His sister was born blind in one eye and has experienced heart problems, while his brother died at the age of 31 from heart failure.

In 2022, Owen, a retired IT worker and business owner, very nearly died from a cardiac arrest himself, aged just 51. He has asked the MoD for his father’s medical records but says so far he has only received a partial disclosure.

Due to Operation Domenic being a US-led exercise (during which Owen says his father witnessed 24 detonations over 78 days), the family has been awarded $75,000 in compensation. “We are in a situation where the US government is paying out to British participants, and that is embarrassing,” he says.

In November, Alan Owen will march alongside 45 nuclear test veterans and their descendants for the annual commemoration of Britain’s war dead at the Cenotaph in London. It will be the second year they will be able to march with their medals, as the Ministry of Defence finally awarded them in 2023, following years of campaigning for proper recognition of their service.

At the Labour conference this week, John Morris was presented with his medal by Burnham. “It definitely means something,” he says. “It means that we have been acknowledged that we existed.”

But he stresses the medal is merely the first step on a long road to justice. “All the veterans want is the truth to come out,” he says with hope that it may now finally happen.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments