Archaeologists draw up ‘oldest family tree’ from relatives found buried together 5,600 years ago

Finding offers ‘unprecedented insight into kinship in a Neolithic community’, say researchers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Archaeologists have pieced together what they think is the oldest ever family tree, following the analysis of DNA recovered from a Neolithic burial site in the UK.

The remains of 35 people, who are believed to have lived between 3700 and 3600 BC, were found entombed in the Hazleton North long cairn, located near Cheltenham in the Cotswolds.

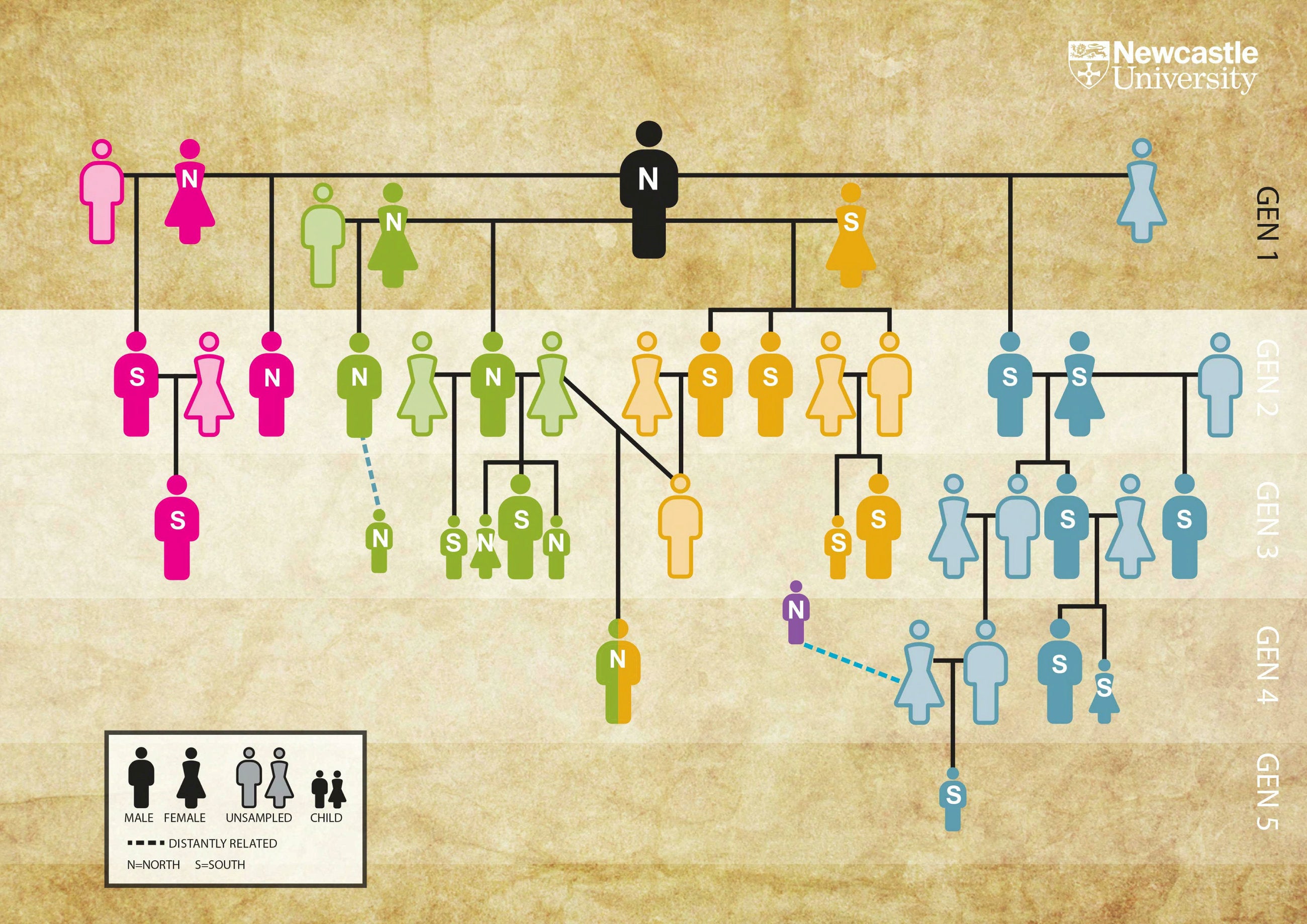

An international team of experts from universities in Britain, Austria, Spain and the US discovered through DNA in bones and teeth that 27 of them were biologically related, as they were descended from four women who had children with the same man.

The research, published in Nature on Wednesday, provides new insights into kinship and burial practices in Neolithic times, the authors said.

The 27 relatives, who all share one male ancestor in common, belonged to five continuous generations of a single extended family, according to the researchers. But they also believe that other individuals may be step-children, suggesting blended families may be far from a recent phenomenon.

Men were generally buried with their father and brothers, suggesting that descent was patrilineal, with later generations buried at the tomb connected to the first generation entirely through male relatives.

Given that only two daughters, both of whom died young, were buried along with their male relatives, the academics believe that adult daughters could have been interred elsewhere with their partners.

The discovery in the tomb of males whose mother was also in the structure but not their biological father indicates that stepsons were adopted into the lineage, the researchers said.

The eight other people in the tomb were not genetically related to the 27 family members, suggesting that other factors also played a role in burial inclusion.

Chris Fowler, a lecturer at Newcastle University who led the study, said its findings offer “an unprecedented insight into kinship in a Neolithic community”.

Inigo Olalde, the project’s lead geneticist who works at the University of the Basque Country and Ikerbasque, said the discovery was down to good DNA preservation as well as recent leaps in technology.

“The excellent DNA preservation at the tomb, and the use of the latest technologies in ancient DNA recovery and analysis, allowed us to uncover the oldest family tree ever reconstructed and analyse it to understand something profound about the social structure of these ancient groups,” he said.

The study, which is published in Nature, was a collaboration between archaeologists at the Universities of Central Lancashire, Exeter, Newcastle and York, and geneticists from the Universities of the Basque Country, Vienna and Harvard.

Additional reporting from PA

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments