Because of Brexit, British Jews whose families once fled the Nazis are applying for German passports

In August, the German Embassy in London confirmed it had received over 400 inquiries regarding citizenship in the seven weeks following the EU referendum

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the months since Britain's shock vote to quit the European Union, tens of thousands of Britons have applied for Irish citizenship, desperate to maintain their ability to live and work within the 28-member state bloc. The prospect of a “Brexit” compelled them to seek documents that didn't sever their connection to Europe and its system of open borders.

But it has also affected a different and long-standing community in Britain. According to recent data, the number of British Jews applying for German citizenship has gone up exponentially this year. In August, the German Embassy in London confirmed it had received over 400 inquiries regarding citizenship in the seven weeks following the Brexit referendum, at least 100 of which had turned into full applications. In previous years, the figure for those inquiries usually never eclipsed 20 or so.

What's striking about this phenomenon is that it involves Britons whose ancestors desperately fled Nazi rule in Germany and Austria in the 1930s. They grew up with the memory of their parents' or grandparents' traumatic uprooting, the loss of loved ones in the Holocaust and the bitter struggle for acceptance in a British society that reluctantly opened its doors to Jewish refugees before the start of World War II. Their ancestors were stripped of their German citizenship by the Third Reich; in the years after the defeat of the Nazis, the German government made it possible for the descendants of these refugees to have their citizenship reinstated. (An increasing number of Jewish-Americans, too, have applied in recent years for German citizenship.)

As my colleagues report, the aftermath of the Brexit referendum has seen a spike in hate crimes and bigotry in Britain, particularly aimed at the country's diverse mix of immigrant communities.

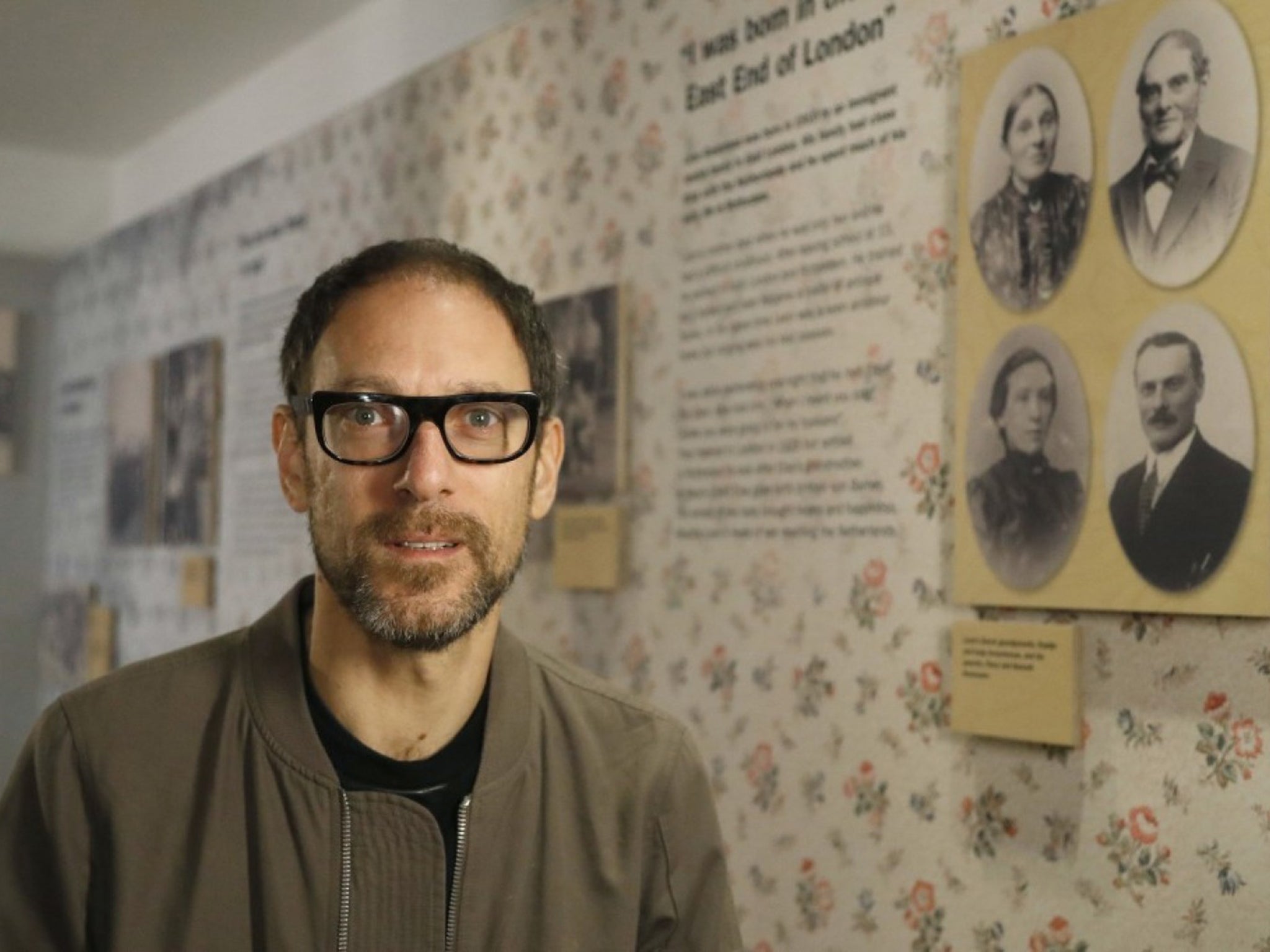

“It's blame the foreigners,” Ben Lewis, a documentary film maker, told the Associated Press in a recent story on the unease of some British Jews. “It's like the 1930s all over again.”

Separately, hundreds of British Sephardic Jews have also checked in with the official Jewish community organizations in the Portuguese cities of Lisbon and Porto. Since a 2013 law was passed, Jews certified by these communities as descendants of the Sephardic population expelled hundreds of years ago by the Inquisition can claim Portuguese citizenship.

Michael Newman, the executive director of the Association of Jewish Refugees, which was founded in 1941 to assist refugees settling in Britain, told reporters that he has submitted his own citizenship application and that his organisation has fielded hundreds of inquiries from other British Jews eligible for German citizenship.

“It is somewhat ironic that we were founded partly to help people become naturalized British after the war and, 70 years on, we find ourselves in the position of assisting people who want to acquire German and Austrian citizenship because of the recent developments in Britain,” Newman told Britain's Guardian newspaper.

The same story cites Oliver Marshall, a British historian of international migration, whose grandparents were once apple-wine producers from the outskirts of Frankfurt and who fled Germany during the war.

“Brexit is closing doors and getting a German passport is opening doors for us,” he said. “If there’s anything Jewish about me, I think, it’s that I want to keep things open, as you never quite know what might happen.”

The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments